Coworking Companies Like WeWork, Industrious Pivot to Thrive Beyond COVID

Operators hope changes that they’ve leaned into since the pandemic began will bring them out the other end

By Nicholas Rizzi February 12, 2021 12:30 pm

reprints

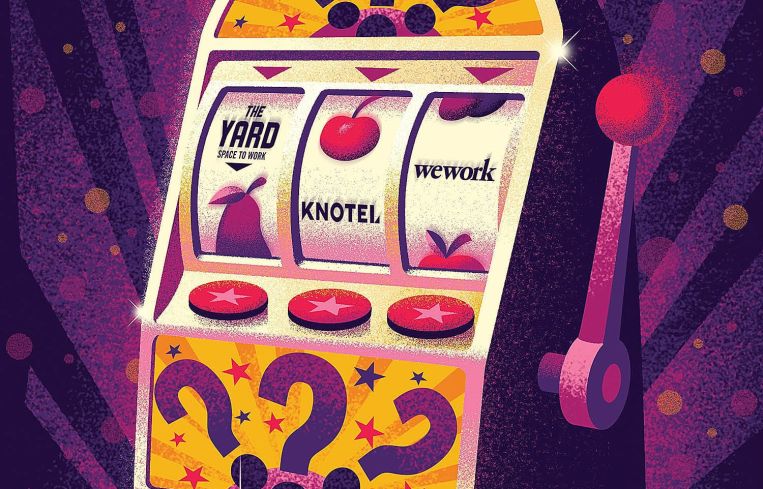

Times look grim for the coworking market.

Despite coronavirus vaccines slowly rolling out, offices and coworking locations around the country still remain largely empty as workers stay home and major employers, including Salesforce and Twitter, announce permanent remote work options for staffers.

WeWork has ditched locations around the country and Regus has done the same by putting entities tied to outposts into bankruptcy. Flex office provider Knotel filed for bankruptcy earlier this month, a little more than a year after it was crowned a unicorn, to be acquired by Newmark, while Breather shuttered all of its locations to switch to an online-only platform. Breather CEO Bryan Murphy told The Globe and Mail that, “Breather, in its current form as an operator, doesn’t make sense, and, to be frank, I’m not sure it ever made sense.”

Even with the doom-laden headlines and Murphy’s questioning of the business model, operators, brokers and analysts aren’t placing bets against the coworking market.

“Coworking going forward, for the survivors of the pandemic, are actually in a very good niche of office space,” said Alexander Snyder, an analyst at CenterSquare Investment Management, who follows the flex office market. “In a post-pandemic world, we have very firmly established flexibility for the average office worker.”

From the early days of the pandemic, operators have long championed that flexibility will be key for companies once employees start to return to the office (whenever that is). Many employers are expected to want to offer workers the ability to have a workspace outside of the home, but without a long commute to the main office, while also retaining employees who may have moved far away from the company’s headquarters during the pandemic.

“Most companies have now come to the conclusion that there are certain hallmarks of what the post-vaccine workplace plan is going to be that are common to many businesses,” said Jamie Hodari, CEO of flex office provider Industrious. “Greater geographic distribution, allowing employees the choice of where to live, and finding a way to retain them … and also, on a day-to-day basis, more employee choice on when to come to the office and when to work from home.”

And it might not just be companies adding flex to their portfolio that will be a boon to the market. Ruth Colp-Haber, president and CEO of brokerage Wharton Property Advisors, said she expects tenants with leases expiring in the coming months to turn to flex to figure out their next move.

“Employers are facing so many questions and tremendous uncertainty regarding all their office space decisions,” Colp-Haber said. “Flex space lets them push these decisions down the road, so they can see what happens when the market returns to normal and their businesses return to normal.”

This goes a long way toward explaining why, despite the Knotel and Breather news, coworking remains a durable business. There are plenty of signs in the market, too.

Brooklyn-based provider The Yard announced last week that it will convert a shuttered Herald Square hotel into flex office space. The Wing, which was reportedly close to a bankruptcy filing last year, received a lifeline with an unknown funding amount from coworking parent company IWG.

Industrious bucked the trend of shuttering locations and added 1 million square feet of new space in 2020. It estimates it will add about the same amount for this year and has been jumping into spaces vacated by its competitors.

“A lot of companies are shedding spaces not because they don’t want them, but because they’re in a cash crunch and they have a high cost that they’re having trouble meeting,” Hodari said. “That’s a little less applicable to us.”

One of the things Industrious has done is focus on only signing management agreements, which can split the revenue with property owners. That leaves them off the hook for pricey and expensive leases that have been the death knell for other providers.

Perhaps the most surprising turnaround is WeWork, which CNN once called the “poster child” for everything wrong with tech startups in the wake of its disastrous initial public offering in 2019.

Under the leadership of CEO Sandeep Mathrani, a real estate legend credited with steering mall owner GGP out of one of the worst real estate bankruptcies in history, the company has focused on cutting its huge cash burn to try and become profitable by the end of the year.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has fundamentally changed the way we work, and has accelerated a new way of working that would otherwise have taken decades to unfold,” a WeWork spokesperson said in a statement. “With our global footprint, great locations, and strong balance sheet, WeWork is the only company that can meet this new demand for turnkey flexible space at scale.”

A source familiar with WeWork’s financials said the company cut its cash burn nearly in half from a peak of $1.4 billion in the fourth quarter of 2019 to $571 million in the third quarter of last year. It has also been able to reduce its long-term lease liabilities by more than $1.5 billion so far. And WeWork has slashed functional expenses by more than 50 percent as of the third quarter of 2020.

WeWork has done that by shedding underperforming locations around the country, which the source said started before the pandemic, and WeWork has been able to work with landlords to exit more than 100 outposts. It also renegotiated leases with owners at its best sites, laid off staff, launched a new subscription platform, and sold off acquisitions, such as Meetup, made under Adam Neumann’s stormy leadership.

“[Mathrani] focused WeWork on their core competency,” CenterSquare’s Snyder said. “Adam had them going in 100 different directions. Sandeep said, ‘We’re good at coworking, let’s just do that.’

“I think they’ve put themselves in a position that, once the world starts to reopen, that they will recover in a strong way,” Snyder said.

Mathrani publicly floated the idea of a second IPO once WeWork becomes profitable, and last month The Wall Street Journal reported that it’s considering going public through a blank-check company, which will allow WeWork to circumvent the scrutiny of the IPO process.

“The benefit of the IPO is you do the dog and pony show, you talk to a bunch of investors, and you really get a feel for what your company is worth,” Snyder said. “WeWork has already done that … I think they are very reasonable to skip the information roadshow and get right to it.”

WSJ reported that the merger with the blank-check company could value WeWork at around $10 billion. That’s a huge drop from its peak $47 billion valuation in 2019, but an improvement over its more recent $2.9 billion valuation, and one that Snyder said is not an “outrageous” number for WeWork in its current state.

But even with the positive news and headlines surrounding WeWork lately, the company and the coworking market broadly still have a long way to go before they’re in the clear.

In the third quarter of 2020, WeWork saw its revenue drop 8 percent compared to the previous quarter, while its membership numbers fell 11 percent in that same time frame, Bloomberg reported. The company is also facing complaints from members over its aggressive collection methods during the pandemic.

And, even if most expect WeWork to come out of the other side of the pandemic, the same can’t be said for other providers, who are likely unable to hold on until the expected demand picks up as people return to offices.

“I think they’ll be a few more moments of either thinning out or consolidation in the industry; then I will expect the late summer or early fall to be a little clearer on where the dust settles,” Industrious’ Hodari said. “We’re probably in the final six months of finding out that question of who made it and who didn’t.”

Part of the problem for other providers, especially ones which lacked a deep-pocketed backer like WeWork’s SoftBank Group, was that they expanded too rapidly with expensive leases. A former Breather employee previously told CO that the company overpaid for offices in Manhattan to remain competitive and justify its $122 million in venture funding.

“The neighborhoods that Breather wanted to be in were also the neighborhoods that Knotel wanted to be in, that WeWork wanted to be in,” the former employee said. “It really artificially inflated the market.”

In a booming market, those issues can be pushed through, but the wheels fell off during a worldwide pandemic that emptied all of their spaces overnight.

“The mismatch between assets and liabilities was always the Achilles’ heel of these companies, and that really came to bear during the pandemic,” Snyder said.

Knotel also threw money around to expand its footprint rapidly and to be able to achieve unicorn status. When the pandemic hit, the company went through two rounds of layoffs and started to shed huge chunks of its portfolios. However, that left it with a growing number of lawsuits from landlords over millions of dollars in unpaid rent.

“When things broke down with the landlords and the landlords started suing, it put the company in an untenable position where they didn’t have the cash flow to sustain operations,” said Jonathan Pasternak, a bankruptcy lawyer at Davidoff Hutcher & Citron. “Basically, they were forced to go into bankruptcy for a quick sale.

“Without them making an offer, the thing would’ve likely just imploded,” he added of Newmark’s takeover bid.

Brokerage Newmark — which previously invested in Knotel — provided Knotel with about $20 million in financing and made a $70 million stalking-horse bid to acquire the flex operator. A spokesperson for Newmark declined to comment and a spokesperson for Knotel did not respond to a request for comment.

(Disclosure: Observer Capital, led by Observer Media Chairman and Publisher Joseph Meyer, is a Knotel investor.)

The move makes perfect sense for Newmark. The company is able to salvage its investment into Knotel, while giving it a flex office platform to meet the expected surge in the market and join landlords like Tishman Speyer and rival brokerages like CBRE with their own coworking brands.

“It’s now becoming very common for the big landlords to have their own coworking facilities,” Wharton’s Colp-Haber said. “There’s just a lot of need for easy and short-term space, and Newmark, they’re talking to tenants and they hear it.”

As for Knotel, Newmark’s name could help save its reputation in the city’s commercial real estate market, since its spaces tended to be overpriced and it became known it didn’t pay brokerage commissions in a timely manner, Colp-Haber said.

“The minute that word got out, no broker was bringing them tenants,” she said. “The fact that they were overpriced and the fact that you may not collect your commission means you’re dead to brokers.”

It’s unclear exactly how many locations Knotel will be left with once Newmark takes it over, but a filing with the New York State Department of Labor showed Newmark plans to continue to employ “many, if not most” of the 106 Knotel staffers in the city.

But not everybody sees Newmark’s purchase of Knotel as a slam dunk or reflective of the true value of the company. Source Media, owned by Meyer, filed a motion in bankruptcy court to slow the “rushed” 10-day stalking-horse sales process to allow more bidders to potentially show up.

Pasternak and Eric Haber, Colp-Haber’s husband and a former bankruptcy attorney, both said the quick timeline isn’t atypical in procedures like Knotel’s.

“It’s not uncommon,” Haber said. “It just means that those competing bidders have to work fast.”

While other operators are hanging off the precipice and could face the same fate as Breather and Knotel, it seems clear that there’s going to be plenty of demand for flex models in the future.

Providers are increasingly optimistic about the sector’s future, and a Colliers International report expects the number of coworking and flexible workspace locations to double or triple around the country within the next five years.

Industrious’ Hodari said the conversation from companies about the need for flex in the future has quieted the real estate execs who threw shade at coworking previously.

“I think behind closed doors, there are no skeptics left in the commercial real estate world in accepting the rising demand in what we do,” Hodari said. “They’ve coalesced around this idea that, in general, COVID is going to accelerate the shift from the legacy way of doing commercial real estate to workplace as a service.”