Downtown Manhattan’s Office Market Struggles With Pandemic Fallout

It hasn't seen this much sublease space up for grabs since 2002, with tenants exiting deals and rents stalling

By Tom Acitelli March 5, 2021 11:59 am

reprints

Around the start of 2021, Cushman & Wakefield decided to consolidate its Downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn offices in one downtown location.

As part of the transition, C&W told Commercial Observer it would be subletting approximately 10,000 square feet at 1 World Trade Center. The move — coming as it did from one of the world’s largest commercial real estate services firms — underscored a potentially historic trend in downtown: the submarket hasn’t seen this much office space available for sublease in nearly two decades.

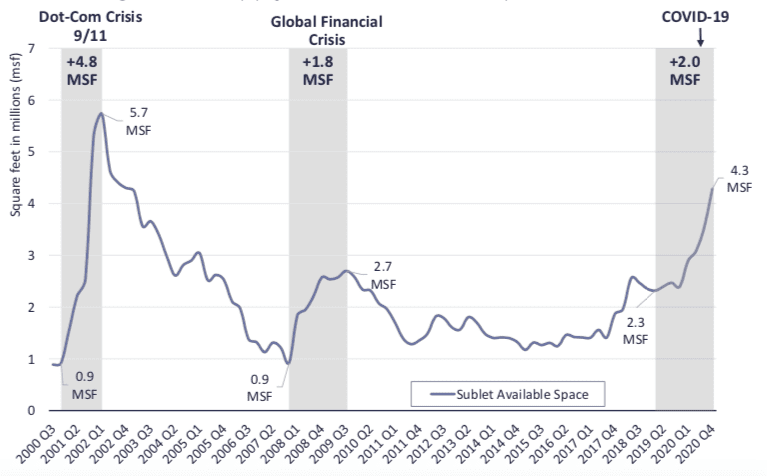

The last time there was this much space in Downtown Manhattan was in 2002. It was then that the 9/11 terrorist attacks and the dot-com bust — and a national recession — either emptied offices or had skittish tenants putting their spaces on the block in hefty numbers.

Even the Great Recession five years later didn’t spill as much sublease space onto the downtown market as the coronavirus pandemic and a handful of factors have now.

The amount of Downtown Manhattan office space available for sublease increased by 2 million square feet during the seven quarters from the end of the first quarter of 2019 through 2020, as the coronavirus pandemic cleared offices and torched companies’ long-term planning, according to a report from brokerage Savills prepared by tri-state research director Danny Mangru.

That brought the downtown total to 4.3 million square feet of sublease-able space by the start of 2021. That was ahead of the peak of 2.7 million square feet amid the Great Recession from 2007 to 2009, and well behind the 5.7 million-square-foot peak in 2002.

No one expects the current downtown market to crest that 5.7 million-square-foot peak from 19 years ago. Instead, it might land somewhere between 4.5 million and 5 million. The vaccine rollout has analysts predicting a slowdown in tenants spilling their space on to the market as office workers trickle back to the office — though no one’s quite sure on what timeline and in what amount.

It will likely be mid-decade, in fact, before Manhattan as a whole reaches pre-pandemic demand levels for office space, according to an analysis earlier this year from ratings and research firm Moody’s Analytics. Rents, too, are not expected to flirt with pre-pandemic levels until the same time.

“Conversations are happening more and more now than in previous quarters, but this is still a kind reassessment period,” Mangru said.

Meanwhile, the bounce in sublease space continues to distort the downtown market. As a large volume of sublease space often does, it’s creating bargains in buildings never built or financed to provide those bargains, and it’s throwing off a false sense of market demand. It’s also, it should be noted, providing opportunities for tenants who might otherwise never get to test the waters in top addresses through what are generally shorter and cheaper subleases.

Take rents as an example of the distortion. The average asking rent for downtown sublease space stood at $54.36 a square foot by the end of February, according to Franklin Wallach, Colliers International’s senior managing director for New York research. The average for directly available space was $64.40 a square foot. That makes sublease space downtown a 15.6 percent discount compared with direct.

The biggest blocks of space up for sublease in downtown by late February were S&P Global’s 205,700 square feet at 55 Water Street, Emblem Health’s 163,000 feet in the same building, finance firm MSCI’s 107,000 square feet at 7 World Trade Center, and Fitch Ratings’ 104,500 feet at 33 Whitehall Street, according to Savills’ Mangru. There were further blocks of between 75,000 and 90,000 square feet at 1 Liberty Plaza (Virtu Financial), 195 Broadway (luxury retailer Moda Operandi), and 1 World Trade Center (Moody’s).

Tenants from the technology, advertising, media and information (TAMI) sector accounted for 26.6 percent of new sublease space downtown from the end of the third quarter of 2020 to late February of this year, according to Mangru. Financial services and insurance companies accounted for 25.3 percent, with business and professional services firms a distant third at 13.7 percent.

The current distortion that has such key industries opening up blocks in marquee addresses is due only partly to the coronavirus. Instead, a convergence of trends was already spilling sublease space on the downtown market when COVID struck.

For one, a variety of industries, including major office users like banks and law firms, have for several years been reassessing how much space they actually need in New York and elsewhere. This involved consolidating offices — Goldman Sachs famously combined several offices into a new Downtown Manhattan headquarters in 2009 — and packing more employees into them.

Examples abound. Financial services firms occupied 17.8 million fewer square feet in Manhattan in early 2020 than they did a decade before, according to brokerage JLL. Law firms in 2019 had fewer square feet under lease in the 10 largest U.S. cities for legal services employment, including New York, than in the prior 10 to 15 years, according to brokerage Newmark.

At the same time as tenants densified and consolidated their office usage, office development continued apace nonetheless. There were 7.5 million square feet of office project completions in Manhattan alone in 2013 and 2014, according to an analysis from Moody’s Analytics. A further 10.5 million-plus dropped in 2018 and 2019.

These included high-profile projects, such as Hudson Yards and the rebuilt World Trade Center, but also less-heralded developments. And this was just Manhattan. Other areas of the city — Brooklyn, especially, where there is 4 million square feet of new, Class A space coming online by 2024 — also added offices for lease.

There were signs along the way that this might be too much space for the market. Absorption of Manhattan office space was negative in 2015 and 2016, according to Moody’s.

But the vacancy rate in Manhattan kept declining through the decade, from above double-digit percentages, to near 8 percent before the pandemic. Moreover, New York City kept adding jobs — a record 4.67 million from the end of the Great Recession in 2009 into 2019, according to the state Labor Department.

It seemed, as some pundits predicted, that Manhattan would, in the end, have plenty of demand to gobble up any and all new office space as it became available. Yet, the ground was already shifting under the market, and the pandemic accelerated those shifts — and other shifts that had barely registered among market watchers before.

Work from home — or at least a hybrid work model full of third places, as well as the home office and the conventional pre-pandemic workstation — is here to stay in a bigger way than ever before.

“I’ve been in the office since the 23rd of June, but that newfound flexibility will accelerate and people will work where they need to work for the task at hand,” Toby Dodd, Cushman & Wakefield’s tri-state president, told CO in early January, when explaining the company’s decision to consolidate space downtown. “So, it may be that people spend a day working from home, it may be they spend a day working from a third place; they spend a few days working from an office.”

Several surveys in the latter half of 2020 revealed a strong preference among executives and employees toward a hybrid or largely WFH model. That feeling seems to have outlasted news of coronavirus vaccines, too. A PricewaterhouseCoopers survey of office workers in November and December found that fewer than 1 in 5 execs expect a return to the office on the scale of what was normal pre-COVID.

What’s more, TAMI was supposed to pick up the slack from companies switching to hybrid or shedding offices completely. The tech-heavy sector has accounted for some of the largest and most high-profile Manhattan office leases over the past several years, such as Facebook’s 730,000-square-foot lease at the under-redevelopment Farley Post Office, the largest new Manhattan lease of 2020; and Condé Nast occupying 1 million square feet at 1 World Trade beginning in 2014.

Yet, the sector leads in subletting downtown space of late — Condé is reportedly trying as of January to unload much of its 1 World Trade space.

All of which means that more companies than at any time since the start of the century are looking to further consolidate and densify — or, at least, to escape the costs of their leases — including in Downtown Manhattan.

In the meantime, too, relatively few companies are taking direct space. The downtown market submarket saw only 70,000 square feet in new leasing in February, about the same as January and well below the 570,000 in February 2020, according to Colliers. Overall availability, too, stood at an eight-year high in February of 15.6 percent.

Some 28 percent of available downtown office space at the end of February was sublease space, according to Colliers’ Wallach. That’s above the 26 percent share that sublease claimed in the third quarter of 2008, its Great Recession high. It’s well below, though, the 43 percent share seen in early 2002.

Downtown Manhattan’s sublease space surge, then, might already be past its peak. Or not.

In the first week of March, JPMorgan Chase, New York’s biggest private user of office space, said it would be subletting just under 700,000 square feet at 4 New York Plaza in downtown. A bank spokesman told Bloomberg that it was part of a general consolidation ahead of JPMorgan’s 2.5 million-square-foot headquarters planned at 270 Park Avenue by 2024.

Also, in the first week of March, the city’s Independent Budget Office predicted a “slow … fragile” economic recovery for the five boroughs in a report prepared by economist Cole Rakow. That includes employment not returning to pre-pandemic levels until 2025 — and an assumption that a lot of jobs won’t need New York City office space.

“Permanent changes to employment-based location decisions could serve to encourage a shift toward employment in sectors that can more easily accommodate employees living outside of the city at the expense of employment in local services for the city’s resident population,” Rakow wrote. “All of this remains uncertain, and will be affected by the speed and efficacy with which the impacts of the pandemic can be overcome.”

Right now, the experts say the Manhattan office recovery will start in 2023.

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)