Retail Bankruptcies in 2020: How the Fallout Will Play Out

By Larry Getlen December 15, 2020 7:55 am

reprints

It’s the perfect summation of 2020 to say that, in the commercial real estate industry, it was a much better year to be a bankruptcy lawyer than a retailer.

While a certain amount of retail bankruptcies is to be expected, especially over the past few years, as e-commerce has provided staunch competition for brick and mortar, the pace of this year’s retail bankruptcy news has been dizzying.

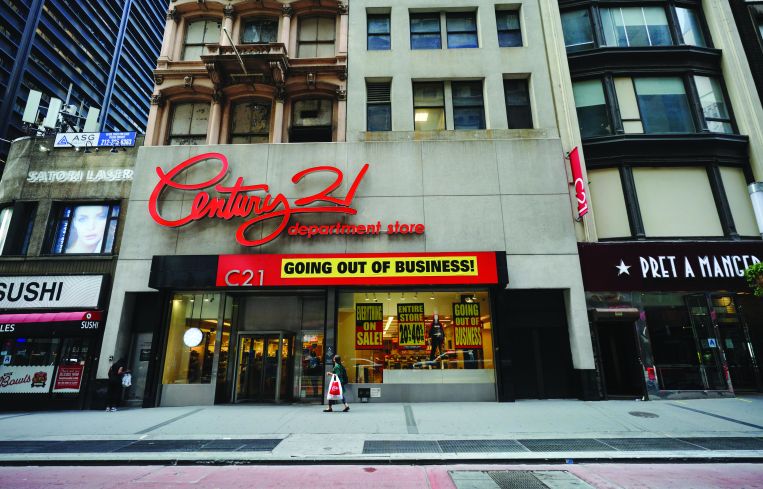

Neiman Marcus, JCPenney, Brooks Brothers, Lord & Taylor, CEC Entertainment (parent company of Chuck E. Cheese), Pier 1 Imports, Modell’s Sporting Goods, J.Crew, Century 21 Department Stores, Aldo, and Guitar Center are just a few of the many companies that filed for some form of bankruptcy in 2020.

“The past 12 months have been a bloodbath,” said James Famularo, president of Meridian Retail Leasing. “[For brands like] Modell’s and True Religion, the writing was on the wall. But Neiman Marcus, J.Crew, Brooks Brothers — these companies are iconic. They’ve been around for generations. It’s mind-blowing.”

Not all of the bankruptcies have been death knells. While some brands, like Lord & Taylor and Century 21, are gone for good, companies including Neiman Marcus, Brooks Brothers, and Ascena Retail (parent company of Ann Taylor and Lane Bryant), among others, will survive their filings, albeit with a smaller retail footprint.

While the COVID-19 pandemic certainly accounts for the sheer breadth of the list, it’s just one factor in many of the bankruptcies, and often, more of a final straw than a primary cause.

“The fundamentals [for many of these companies] have been wrong for a long time,” said Kate Newlin, CEO of Kate Newlin Consulting. “I think if we didn’t see [these bankruptcies] this year, we would have seen them next year. There’s nothing urgent that was driving people back into the mall. There was a systemic erosion underneath, and as long as they could mask some of that by selling things at discount, they could have skated for another year, maybe. But COVID was a hard stop. It was a fast-forward to the ultimate outcome, but it wasn’t the only cause of it, certainly.”

In many cases, the COVID-19 pandemic merely accelerated a process ignited years ago by online competition, or bad decisions, or by the takeover of some of these companies by private equity firms that demanded dividends and ladened the retailers with debt.

“The headline is that it’s all about COVID, but there are enough examples of businesses that don’t have something really distinguishing them. They just got to that endpoint a little bit quicker because of COVID, which maybe shaved off 18 months,” said Soozan Baxter of Soozan Baxter Consulting.

“Pier 1 is a brand that, quite honestly, couldn’t keep up,” she said. “They got outsmarted by some of the innovation and creation from others in the business. Look at Target, and juxtapose that with the offerings at Pier 1. You can probably get everything that Pier 1 sells at a better price, and maybe with a brand. So, why do you need to go to Pier 1 anymore?”

“I wouldn’t lay it all at the feet of COVID for Neiman Marcus,” said Newlin. “The Hudson Yards [store] was a catastrophe well before COVID. So, I think there were missteps along the way that COVID certainly made terminal more quickly.”

The cumulative effects of these bankruptcies and other store closings found the national retail vacancy rate at 20 percent by mid-year, according to the National Association of Realtors, leaving a glut of space that could have effects beyond retail.

After Neiman Marcus closed its Hudson Yards store in July, co-developers Related Companies and Oxford Properties announced they would re-market the space for office use. While this is understandable, given the negative prognosis for retail, COVID-19 has made the fate of office tenuous, too. If developers attempt to convert retail space to office in larger numbers, that could merely spread the misery.

“That’s an even bigger problem,” said Jonathan Pasternak, a partner in the bankruptcy practice at Davidoff Hutcher & Citron, “because not only do you have some retail vacancies, but you would end up potentially with a lot of office building vacancy. And that’s where I think you’re going to see the next trend in bankruptcy. You’ve got owners in Midtown Manhattan, the Financial District, and in every city across the country, where people haven’t been going to their office and businesses have not been paying their full rents. There’s gotta be fallout to that.”

And, while the retail bankruptcy trend overall is bound to have ramifications, some of the companies that filed for bankruptcy are significant enough to affect the retail landscape on their own.

“With [a company like] GNC, their stores are little, only 1,000 to 1,500 feet, but there’s 5,000 stores,” David Firestein, managing partner at SCG Retail, said of the supplements retailer, which announced in June it would close almost 25 percent of its stores and revealed its sale to China-based Harbin Pharmaceutical Group in October. “It’s very impactful because it’s pushing so much space back into the market.”

“When you look at Ascena, and how many brands and how much square footage they have, that will probably take a dent out of some B malls, and definitely out of the outlet industry,” said Baxter. “That’s a meaningful company that just vanished.”

Newlin believes the effect on malls will be more than just a dent.

“You’ll see [stores] like JCPenney get new ownership that will try to make it a legitimate shopping destination,” Newlin said of the legendary retailer, which is exiting bankruptcy protection having sold the bulk of its assets to Simon Property Group and Brookfield Asset Management. “But, essentially, without a powerful re-imagination of what it means to shop, it’s just the IV drip of the end of times for physical retail.”

Across the board, the apparel sector has been one of the hardest hit by bankruptcies. Given the ease of shopping online for clothes, it’s hard to be optimistic about the sector’s future.

“The volume of clothing retailers that have gone into bankruptcy will really make surviving retailers apprehensive about opening new stores in the future,” said Meridian’s Famularo. “Most would probably opt for online sales, if not pop-ups. We’re getting a lot more calls for pop-ups than normal.”

Making the potential challenge even greater is that, pre-COVID, more experiential uses were an oft-discussed potential savior for flailing retail outlets. But entertainment of all forms has taken, perhaps, the hardest hit of the COVID era, as restaurants flail for survival and the major, movie theater chains — facing both COVID fears and restrictions, and movies being released day and date on streaming services or video on-demand in response — struggle to avoid their own bankruptcy filings.

“That’s one looming out there that makes lots of people nervous, because they impact lots of other tenants,” said Firestein. “If a landlord gets back a J.Crew, it’s a clean box. Even a restaurant already has a lot of the restaurant-related work done. But theater space doesn’t really work well for anybody else. To convert it is very expensive, because you have sloped floors and all kinds of stuff that doesn’t work [for other businesses].”

With all of the dire news and forecasts, there are some bright spots on the retail horizon. Baxter notes that athleisure and cosmetics are doing well, and the recent announcement that Harry Winston is nearly doubling its Fifth Avenue space demonstrates the staying power of jewelry sales.

“Harry Winston’s expansion really speaks to the category, the power of Fifth Avenue, and the belief that retail is going to come back,” said Baxter.

Pasternak, meanwhile, sees the slew of bankruptcies as opportunities for right-sizing.

“Bankruptcy gives these companies an opportunity to shed some leases, get leaner and meaner, and clean up their balance sheet,” said Pasternak. “I think these things are ultimately going to be good for the retail economy, because they’re going to lead to more efficiencies and a better chance of profitability of recovery for return on investment.”

Baxter also sees an upside in the basic life cycle of business — that, for every death, there can be a new birth.

“A lot of these brands will go away, but every time you see a brand go away, imagine that there’s probably 15 entrepreneurs sitting out there that are the next Jeff Bezos or Tory Burch,” said Baxter. “People are innovating all the time. For every brand that gets discussed in a ‘oh my gosh, rest in peace’ sort of way, there are others coming up that are really exciting, and also brands changing the way they’re doing business.”

Based on his deal volume throughout the pandemic, Famularo agreed, noting that one brand’s capitulation to inevitability is another brand’s golden opportunity.

“New York will bounce back. Are we going to reach the same rent levels we were at a few years ago? I don’t think that’s going to happen in our lifetime,” said Famularo. “But my team and I have closed almost a hundred deals during the quarantine. People feel opportunistic. If you were paying $10,000 a month in whatever business you might have, and I offered [space] to you at $5,000, are you going to wait on the sidelines? You’ll jump in head-first. That’s what’s happening. That’s why I’m saying we’re going to be back. I think come March, April or May, you’ll see the renaissance begin.”