New York’s Casino Race Has No Clear Favorites Six Months Out

Ahead of a December deadline — and despite millions already spent — there appear to be no clear favorites for landing one of three downstate gambling licenses

By Mark Hallum July 21, 2025 7:14 am

reprints

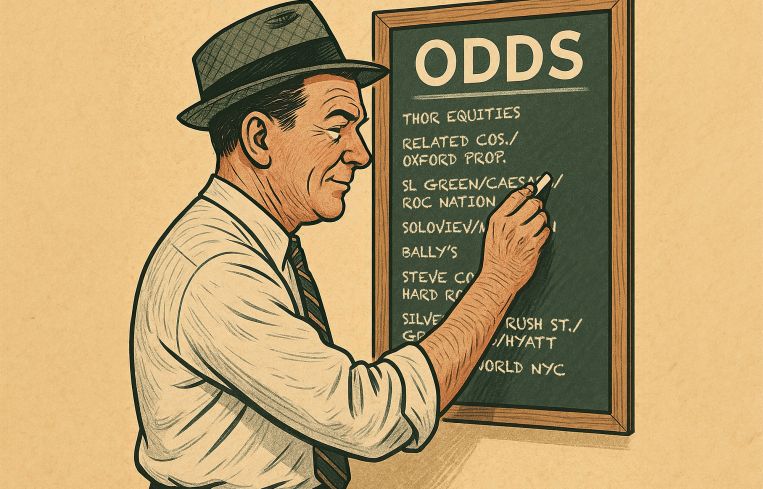

The competition for three new downstate casino licenses in New York is off to the proverbial races with eight partnerships submitting applications on June 27, but who has the edge on nabbing first, place and show?

Not even the betting markets are getting a jump on this game of chance. (Really. You will not find odds on Polymarket or any other betting sites.)

The New York State Gaming Commission and the 47 members of the Community Advisory Committees (CACs) hold all the cards as to which three proposals will get the green light to spend billions building gambling facilities.

There’s a lot of money on the line beyond the $1 million application fee. But, in the end, success will probably come down to four main things:

Which applicant has community support? (Or, probably more accurately, doesn’t have staunch community opposition?) Which offers the most economic and civic benefits? Which is the least disruptive in terms of traffic, transit and existing zoning? And (most difficult to define) which one has the razzle-dazzle necessary for a casino?

All the proposals seem to satisfy these things in various ways — and fall short in others.

New York Mets owner Steve Cohen and Hard Rock International have some pretty huge ambitions in the shadow of Citi Field in Queens.

Their $8 billion project known as Metropolitan Park will add a casino, retail, hotel rooms, park space, 2,500 units of 100 percent affordable housing to the existing ballpark complex, and a soccer stadium for the New York City Football Club under development there. Cohen and Hard Rock believe the casino could produce $3.9 billion in annual revenue within the first three years after opening.

The advantage for Metropolitan Park, according to Spencer Levine of developer RAL Companies, is that being situated in Willets Point it’s outside the densely populated area of Manhattan, on the former site of an auto shop district renowned for its squalor. It also has transit infrastructure from the No. 7 train and Long Island Rail Road. (From an urban planning perspective, minimizing the intrusion in the middle of a dense urban environment like New York City is key, Levine told CO. It also depends on whether the facilities are inward facing — like most casinos — or outward facing, which could make all the difference to those with a say in the matter.)

The proposal has won support from Queens Community Boards 3, 6, 7, 8 and 9. Jessica Ramos, the area’s state senator, declined to champion the project in Albany, but State Sen. John Liu in the neighboring district took up the cause for Metropolitan Park and helped win some of the approvals it needed at the state level.

But Metropolitan Park would nevertheless mean a big project that will cost billions and leave a big footprint in a neighborhood, which can be good and bad. The proposal that may be the least game-changing for the city would likely be Resorts World New York City’s plan to transform the current “racino” — a gaming facility limited to horse racing and slot machines — in southeast Queens into a full-fledged Las Vegas-style gambling house. Plans also include lodging, retail and performance space as well as 3,000 units of housing.

And while this might not mean forging a whole new neighborhood, it will certainly require cash. Resorts World’s proposal is expected to cost $5 billion.

The MGM Empire City Casino in Yonkers is likewise a racino hoping to become a casino, but it could have a foothold with the gaming commission. The Yonkers project sits outside densely populated areas and has drawn minimal local opposition.

But a potential downside for both racinos could be that the state might prefer to award licenses to new gambling houses, which would create greater economic benefits than merely expanding existing gambling sites.

The promise of better economic opportunity is one factor in the $5.5 billion Caesars Palace Times Square proposal at 1515 Broadway, which would be rebuilt under the casino plan. Caesars and the Rev. Al Sharpton, a vocal supporter, announced June 25 that ordinary people will be able to buy equity in its development for as little as $500 per share. But as far as goosing the surrounding area with accompanying restaurants and retail (which a lot of these casinos promise) developers of the Caesars project believe such additions would be unnecessary in already bustling Times Square.

“Unlike other casinos, this is a casino that I would say is amenity light and is relying on the amenity base in the surrounding neighborhood to be the attraction and the co-tenancy, which is a great way to think about an urban casino,” Jamestown’s Michael Phillips told CO back in December 2023. “Most of the people who talk about Las Vegas talk about concerts, theater and food. They don’t talk about gambling. … The gaming culture has created an entertainment engagement that has now to some extent eclipsed the gaming.”

While 1515 Broadway is currently the home of “The Lion King,” the redevelopment will create a new theater for the production with a few restaurants and 992 hotel rooms. The lack of retail is an intentional omission — the developers say they don’t want to take customers away from existing businesses in the area.

The proposed Caesars casino’s developer, SL Green and its partners, hope card tables and slot machines will be a tasteful addition rather than a place that sucks in the masses.

“Our intention with this project is to create a high-end, luxury destination that will attract high-income visitors and gamers from around the globe, as well as local New Yorkers,” Brett Herschenfeld of SL Green said in a statement. “Caesars Palace Times Square will not look like a big Las Vegas casino. For example, we won’t have any gaming on the ground floor. Visitors will need to enter our lobby, go through security, and choose to move upstairs onto the gaming floor — raising the barrier to entry and helping make this an intentional destination for gaming, not a place for impulse gamblers.”

In the end, it might not come down to how enticing a proposal is, but how unified the opposition to it is.

Caesars Palace Times Square believes it could produce $23.3 billion in gambling revenue alone over 10 years, but Manhattan Community Board 5 as well as theater groups like the Broadway League are firmly against a casino in the Theater District.

The majority of the partnerships looking to establish a gaming house have spent years planning, acquiring land, and pushing elected officials to usher in their vision. That includes Thor Equities gaining a rezoning from the New York City Council on June 30 that will allow Thor to build what the company is calling The Coney, a casino complex in Brooklyn’s Coney Island. (Let’s call that a win for the developer, whether or not they actually get the casino.)

The Coney will have not only a casino but also a 500-room hotel, 20 restaurants across 50,000 square feet, a 2,400-seat entertainment venue, a 92,000-square-foot convention center and an acre of green space.

Thor Equities Chairman Joe Sitt has amassed parcels in Coney Island, a place where New Yorkers have gathered for relaxation, theme park rides and freak shows since the days of yore. But despite the City Council awarding a necessary zoning change, Thor’s proposal could get hung up by the CAC thanks to neighborhood groups and Brooklyn’s Community Board 13 opposing the effort.

Community boards are advisory committees without any executive function. Despite the Board 13’s expressed opposition, Thor COO Melissa Gliatta believes the company is slowly bringing people around to the proposal with the prospect of jobs and tourism dollars.

“The economic struggles in the Coney Island neighborhood are real, so being able to talk through real career-building projects in construction, retail or hotel jobs, I think there’s been a tremendous amount of enthusiasm,” Gliatta said. “The neighborhood is seeing the potential for a stronger local economy.”

A rezoning could grant the company the ability to develop the site even if no casino license is awarded. However, Thor simply doesn’t see any way to truly revitalize Coney Island from an economic standpoint without a gaming facility attracting visitors to the beach during the slow winter months.

“I think there is [development potential without the gaming permit], but I’ll be honest with you, we need the casino,” Gliatta added. “The truth of the matter is that we’ve owned this land and have tried to look at different ways to build that up over the years, and it’s just very difficult to create the attraction year-round.”

Gliatta said the proposal also has strength in the fact that it’s the only casino proposal in Brooklyn, meaning that the gaming commission could more evenly spread the benefits of economic development by picking proposals in Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan.

To get support from CACs, many casino bids include major giveaways to the surrounding communities that go well beyond the requirements outlined in the 2013 legislation authorizing the issuance of the three downstate permits, such as affordable housing, community programming and even equity options for New Yorkers. Thor is offering a $200 million community trust fund.

But, if the applicants believe they’re getting ahead with the Gaming Commission, guess again. If CACs don’t approve of plans before Sept. 30, those plans do not advance to the final decision before Dec. 1.

“This is a tabula rasa — there are no front-runners or favorites,” Gaming Commission Chairman Brian O’Dwyer put it in no uncertain terms in a statement. “These eight proposed projects represent billions of dollars in private investment, thousands of jobs, and amenities in addition to a world-class casino — all things that can transform a community. … This ensures that only those projects embraced by the community are placed before the board for consideration.”

Bally’s seems to have landed its ball in the bunker, however, with the City Council voting on July 15 against a zoning change to demap the site as city parkland and give the property mixed-use development rights.

Unlike the Times Square project, Soloviev Group’s Freedom Plaza is fitting as many community benefits into their proposal as possible.

Soloviev and Mohegan’s proposal includes community space, a museum dedicated to freedom, and two towers with 1,000 units of housing, of which 48 percent will meet affordability standards for working-class residents.

“This is not something we’re required to do, it’s something we’re volunteering to do,” Soloviev Group CEO Michael Hershman said in a briefing June 26. “It’s difficult to build affordable and residential housing in the city and make it economically feasible to do so. In large part, we’re able to do this because of the revenue from the integrated resort, which includes the casino and hotel, food and beverage, and the retail.”

Freedom Plaza is also setting aside 12 percent of equity for New Yorkers and city employee pension funds to invest in, which seems appropriate as their plan is backed by unions such as the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York, SEIU 32BJ, and the Hotel and Gaming Trades Council.

Freedom Plaza, however, has failed to win over locals, with Manhattan’s Community Board 6 voting 39-to-1 against the plan in January 2024.

Freedom Plaza projects $2.2 billion in revenue in its first year, which could get as high as $4.2 billion every year after 10 years.

But one final project has the advantage of being in Manhattan — not in the strum und drang of Times Square, but just a few avenues over — and that’s Silverstein Properties, Rush Street Gaming, Greenwood Gaming and Entertainment, and Hyatt’s partnership for a facility at 11th Avenue and West 41st Street within a project they are calling The Avenir. At $7 billion, the casino would be joined by a 1,000-room hotel, restaurant, entertainment venue and 2,000 apartments. Of those, 500 would be designated affordable.

But CAC members for this project are already voicing concerns about traffic due to its proximity to the Lincoln Tunnel as well as the housing component, which they see as a more opaque aspect of the application, CasinoBeats reported on July 18.

Community amenities? Manhattan, but on 11th Avenue? Good operator who has plenty of razzle-dazzle?

We’ll just have to wait until the big reveal on Dec. 1.

Mark Hallum can be reached at mhallum@commercialobserver.com.