Time for Some Traffic Problems in Manhattan

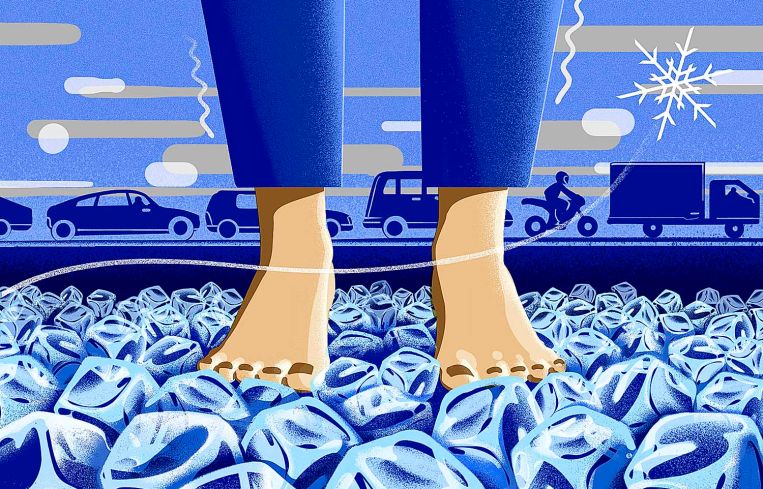

With Gov. Kathy Hochul getting cold feet on congestion pricing, what’s going to pay for transit improvements in the New York area now?

By Aaron Short June 14, 2024 9:03 am

reprints

The New York governor’s legacy-defining choice to back away from a Manhattan tolling program designed to reduce traffic while generating $1 billion in revenue annually for the region’s transit system has managed to alienate the business community, including commercial real estate, as well as lawmakers, advocates and millions of New Yorkers who take transit every day.

If the state’s congestion pricing plan went through as scheduled on June 30, most motorists would pay $15 to enter Manhattan south of 60th Street during peak hours, and traffic would be reduced by as many as 120,000 vehicles per day.

Instead, New Yorkers will get more of the same. The absence of tolls has raised concerns about a series of negative consequences, including scaled-back subway service, deteriorating air quality, and gridlock that already costs the region $20 billion annually and by one estimate could get even worse.

“Many major employers in the city are dependent on the transit system being in good shape,” said Kathy Wylde, president and CEO of the Partnership for New York City, which represents the city’s global employers and studied the effects of congestion. “They need to feel employees are on a safe and reliable transit system, and they’re tired of being stuck and having gridlock in the central business district.”

The governor sprang her decision on the public on June 5, two days before the end of the legislative session, explaining in a taped video announcement that a $15 charge could “break the budget” of working- or middle-class households.

“Given these financial pressures, I cannot add another burden to working- and middle-class New Yorkers — or create another obstacle to continued recovery,” Hochul said.

Her decision to pull the plug on a plan that had already been codified five years ago left transit leaders flabbergasted and state lawmakers dumbfounded after she repeatedly touted the program’s benefits in recent weeks.

In its aftermath, aides to the governor scrambled to craft alternatives to plug the loss of Metropolitan Transportation Authority revenue, including a payroll tax on New York City businesses and a $1 billion annual commitment from the state’s general fund. Both measures failed, and legislators left Albany earlier this month for the rest of the year without solving the MTA’s revenue mess or passing hundreds of other significant bills.

State Sen. Liz Krueger, the Manhattan lawmaker who leads the Senate’s powerful Finance Committee, called Hochul’s decision “reckless” and a “staggering error.”

“The governor is obligated to answer the question of where new revenue will come from not only for this year, but for every year going forward,” Krueger said in a statement. “The legislature certainly will not be rushing to raise taxes on hardworking New York City residents and small businesses.”

After absorbing a week of backlash, Hochul insisted that lawmakers would eventually find funding for the MTA to replace toll revenues. But she doubled down on her conclusion, saying it was “not the right time” to charge drivers to enter central Manhattan.

“There are real lives that are being affected, including everything from the cost of a piece of pizza is going to go up because of the charges imposed and passed onto consumers,” she said at a June 13 press conference in Albany.

Advocates feared that the pause would become permanent and hoped Hochul would change her mind.

“Congestion pricing falls on high-income workers who would save money with faster, more efficient commutes,” Danny Pearlstein, policy and communications director for Riders Alliance, a transit advocacy group, said. “Time is money, and that seems to be escaping the governor right now.”

Seeking alternative routes

Transportation experts believe three scenarios could play out over the next several weeks.

The governor could change her mind and let tolls proceed as scheduled beginning June 30, although this seems unlikely based on her remarks. Hochul has assured some business leaders the pause would be temporary, but has not offered a revised date when congestion pricing would start.

The second possibility is that Hochul could be forced by the courts to continue the program.

Some legal experts have argued that the governor does not have the legal authority to halt congestion pricing. While the state Department of Transportation must sign off on what’s called a value pricing pilot program agreement that would turn on the toll devices and redirect any revenue collected to MTA coffers, that move was a formality until Hochul reversed herself.

City Comptroller Brad Lander announced on June 12 that he and a coalition of transit and environmental advocates were exploring legal action that would compel congestion pricing to move ahead.

Lander said he was still researching plaintiffs, but his coalition’s potential lawsuits would focus on several statutes, including the Americans with Disabilities Act, the 2021 Green Amendment, and the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act.

Finally, Hochul could stall tolls indefinitely, spelling the death of congestion pricing for at least a generation.

One reason why Hochul supposedly nixed the plan was that U.S. House Democratic leaders believed that suburban voters in New York’s swing districts would support the decision, Politico and The New York Times reported. But Republicans have already pledged to make the decision a campaign issue, warning voters that Hochul would simply start the tolls after the elections in November.

Even if she waits until after November to resume the plan, there’s no guarantee she will get support from a Republican-controlled White House or Congress.

“If it’s delayed and the administration in the national government changes, it would be difficult to move on with an administration hostile to the region and the program,” said Rachel Weinberger, transportation chair at the Regional Plan Association.

Unplanned service changes

Hochul assured the press that the MTA’s long list of capital projects would not be derailed.

“Projects will continue,” she said. “They’ll be reprioritized, but they’ll continue. This is a pause, for now. Let us take some time to work with the legislature as they asked us to do.”

But the transit authority’s assessment of a future without congestion pricing revenue is bleaker. MTA CEO Janno Lieber said the agency’s plans to upgrade signals, electrify buses, and make subway stations accessible to people with disabilities could get scaled back in order to ensure the system “doesn’t fall apart.” Subway delays have already risen 30 percent over the first four months of the year compared with the same period last year.

“It may feel right now that things are a little crazy and even there’s a crisis, but we need to stay focused so that we can maximize the situation for our riders,” Lieber told reporters on June 10.

The MTA’s $51 billion capital plan for the next five years was dependent on borrowing based on congestion pricing’s annual $1 billion revenue stream, and there will now be a $15 billion hole in the budget. Some long-term projects such as the second phase of the Second Avenue Subway are dependent on federal matching funds that could be lost if congestion pricing tolls are never turned on. Other ambitious plans, such as the Interborough Express light rail project between Brooklyn and Queens, might never get off the ground.

Several MTA board members have denounced the governor’s congestion pricing delay and urged her to reconsider. The board technically does not have to vote on keeping the June 30 launch since it already approved the tolls, but it may do so anyway. Or the board could consider a significantly modified capital plan at its monthly meetings on June 24 and June 26.

“All of the projects in the capital program are necessary, and it will have a real impact on the reliability of service and expansion projects providing new service to areas in desperate need of transit options,” Kate Slevin, executive vice president at Regional Plan Association, said. “To the extent they need more operating dollars to pay for increased debt, it could put pressure on the fare and could lead to service cuts as well.”

Gridlock alerts

In the meantime, traffic in Manhattan remains almost at a standstill.

Travel speeds in Midtown Manhattan average less than 5 mph, about 3 percent under the previous low in 2019, a June 2024 Regional Plan Association report found.

But gridlock is not just concentrated in Midtown. New York City has rush hour travel speeds 58 percent slower than London and 33 percent slower than San Francisco.

“We have the slowest average speed in our Midtown business district in history,” the Partnership for New York City’s Wylde said. “It’s the lowest speeds and the worst traffic congestion we’ve ever had, and the whole point of congestion pricing was to make a more efficient city.”

One reason traffic has gotten worse is that car ownership in New York City jumped at least 37 percent in 2021. Once the city started to reopen, traffic quickly returned to pre-pandemic levels while subway ridership still lagged. Then it got even slower last year, when drivers took an average of 25 minutes to travel six miles, making New York the most congested city in the country.

RPA’s Weinberger believes there is nothing stopping traffic from getting even worse.

“If you suspend congestion pricing, which means you deteriorate the subway, the worse the subway is and the more people will prefer to drive,” she said. “The elegance of congestion pricing is that it lets you make the subway better because it’s more competitive and drivers realize the fuller extent of their trip.”