A Religious Exemption From COVID Vaccines? God Help You

There are no clear rules, and each state has its own set — yet another complication in companies’ efforts to go back to the office

By David M. Levitt August 19, 2021 9:29 am

reprints

COVID keeps opening up new cans of worms.

First, it tested the ability of businesses to do business with nearly all of its staff operating from home or a coffee shop, anywhere but in the office. And for businesses like hotels and old-fashioned, three-dimensional stores that relied on a mobile customer base, it was, basically, how long can you hold your breath?

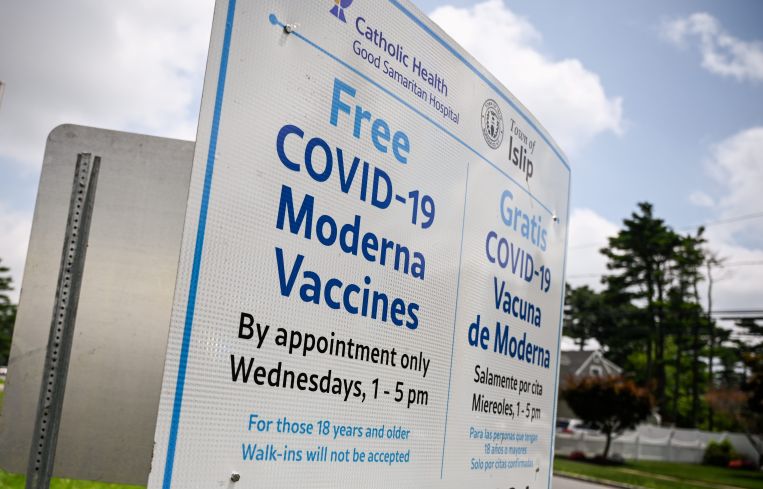

Now, the vaccines are being rolled out in record time. End of story, right? Not if your employees include a few of the recalcitrant.

Federal and most state law allows for a couple of exemptions from vaccine mandates: medical and due to a “sincerely held” religious belief. Many private employers issued comprehensive vaccination mandates, including in the commercial real estate business, such as Related Companies, principal developer of Hudson Yards, and the Durst Organization, part owners and the operator of One World Trade Center.

For a medical exemption, the path is fairly straightforward. Any chronic condition that might be compromised by a shot is likely to be fairly well documented, and, if necessary, a doctor’s note is likely to suffice as proof of the need for the exemption.

But, granting a religious exemption is a thorny process with no clear rules.

This opacity could stymie the return-to-office plans of companies across the U.S., plans already largely pushed back well beyond Labor Day, due to COVID’s delta variant and widespread vaccine hesitancy.

A spokesman for one real estate company that plans on imposing a vaccine mandate on its employees said the company intends to follow existing law. Though COVID is a novel coronavirus — meaning that it’s new, and poses mysteries in how it spreads and how it mutates, which public health authorities are only starting to understand — it’s not the first virus ever, nor is it the first to be fought with a vaccine.

Therefore, there’s fairly well-developed case law and regulations that apply. These include regulations surrounding school-related vaccinations. Six states, including New York, Connecticut and California, do not allow religious exemptions for students (New York ditched its exemption following a 2019 measles outbreak). All of the rest and the District of Columbia allow for religious, or personal belief, exemptions, with some small caveats, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

As for COVID and the workplace, specifically, the most relevant rules are from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, which allow employers to require all employees physically entering a workplace to be vaccinated against the virus, per a May 28 statement.

Still, none of this provides the kind of finality that a doctor’s note can for a medical exemption. Instead, it can be a long, undulating process that begins with compromise — or, at least, the attempt at it.

Whether the employee’s concern is religious or medical, the employer is obligated to make “reasonable accommodations” to allow the person to work. Determining what those accommodations might be “is where the rubber meets the road,” said Michael Passarella, a labor attorney with Olshan Frome Wolosky.

First, the employer must determine whether a worker’s request for a religious exemption is based on a “sincerely held” religious belief, Passarella said. Then, once that hurdle is cleared, the company has to make a reasonable accommodation, which could be as simple as letting the employee continue to work from home.

In New York state, in particular, the employer is under no obligation to bend over backward to accommodate the employee, Passarella said. The law permits the company to avoid complicated accommodations if it is found to be so disruptive as to actually get in the way of conducting normal business.

There’s little in either the Catholic or Jewish liturgies that would preclude receiving a vaccination, Passarella added. But that doesn’t mean someone couldn’t bring to the negotiating table their own personal beliefs, including beliefs not drawn from these two religions or others.

RELATED: How Companies Are Figuring Out Who’s Been Vaccinated

“It doesn’t have to be what would be considered in quotes an ‘organized’ religion,” Passarella said. “It could be somebody’s theistic beliefs. But they have to be sincerely held, and there has to be some explanation about why the vaccination is an issue.”

A letter signed by a friend or a family member might suffice, he said. So long as somebody in HR doesn’t smell a rat. In cases where an employer has reason to suspect someone is making up, or blowing up, some religious objection, an employer might have the right to demand more documentation.

“Agencies have cautioned not to be heavy-handed in their approach, when somebody comes forward with a request for religious accommodations,” Passarella said. “Certainly, I think asking for a little bit more information is going to be OK. But there’s no real set guidance on how much is too much.”

In most cases, the dialogue is internal, and, if both sides are sincere, usually something can be worked out, he added. Hanging over the process, however, is the possibility, if internal dialogue fails, that an outside party could review and pass judgment on whether either side bargained in good faith.

“Typically, when you engage in this process with an employee, you’re a long way away from getting in front of a judge,” Passarella said. “But, ultimately, where would it go? It would go to either the EEOC or the New York City Commission on Human Rights, or the state division on human rights.”

While mainstream Judaism is mostly silent on vaccinations, “strictly observant Jews depend on guidance from their rabbis and rebbes,” Robert Moses Shapiro, a professor of Eastern European Jewish studies at Brooklyn College, said in a reply to an email with specific questions. “Like many Americans, some Jews have doubts about the safety and efficacy of some or all vaccines. The failure of the [Food and Drug Administration] to fully approve any COVID vaccine, but provide only a EUA (emergency use authorization), raises some suspicion and doubt.”

What’s more, “some Hasidic and other Jews do not trust vaccines. One assumes a statement by a rabbi or a Muslim qadi or Christian pope would be sufficient. But freedom of religion is significant and not dependent on having a church hierarchy or establishment. See the First Amendment.” (Indeed, the Framers listed religious freedom first in the Constitution’s initial tweak.)

This individual approach, even in a wider faith tradition, can cut both ways.

For example, one might think that Christian Science, whose perhaps most famous precept is the power of prayer over disease, might present one of the biggest challenges to the vaccination push. But Kevin Ness, manager of the committees on publication at the First Church of Christ, Scientist in Boston — referred to as the faith’s “Mother Church” — said it leaves decisions about vaccines up to members.

“One’s views on these matters are highly individual and thoughtfully considered as a matter of personal religious choice and as the result of demonstrated spiritual practice,” he said, “not as a function of church doctrine or dogma.”