Delivering Amazon: This Is What’s Right and Wrong With the City’s Pitches for HQ2

By The Editors October 25, 2017 10:00 am

reprints

Earlier this week, The Associated Press reported that Amazon received 238 proposals from cities and regions that want to house its second North American headquarters.

Indeed, Amazon has a lot to offer: a promised 50,000 jobs and $5 billion to spend. Everyone—including Gotham—wants in on the action.

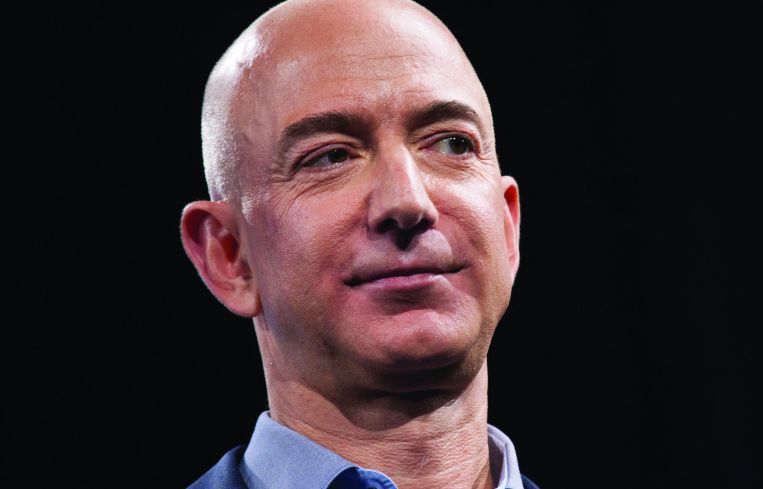

In its attempt to lure Jeff Bezos to our city, New York hasn’t shown this much leg since The Deuce era.

More than 70 elected officials—from Public Advocate Letitia James, to Manhattan Borough President Gale Brewer, to City Council Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito—signed a statement touting New York City’s accessibility to both Boston and Washington, D.C.; its commitment to sustainability; Citi Bike and the largest subway system in the world (wisely, nobody mentioned MTA’s “summer of hell”) and “affordability”—as in, the fact that the administration has promised 200,000 affordable housing units over the next 10 years. (Friendly advice: The word “affordability” isn’t something that really works to New York’s advantage in real estate matters. But too late now.)

“Companies don’t just come to New York,” Mayor Bill de Blasio wrote in his seduction letter. “They become part of New York.”

In its official presentation, the New York City Economic Development Corporation proposed four different neighborhoods that could conceivably do the job: Lower Manhattan, the Far West Side, Long Island City and Downtown Brooklyn.

And while everybody weighs in (Moody’s pegged New York’s chance of landing Amazon as sixth in the country—after Austin, Texas; Atlanta; Philadelphia; Rochester, N.Y.; and Pittsburg—as per a New York Times story), it’s worth considering the four areas up for consideration, what they all have to offer and what the NYCEDC probably won’t mention.—Max Gross

Lower Manhattan

Over the 16 years since the Sept. 11, 2001, World Trade Center attacks, Lower Manhattan has been transformed from a financial district to a commercial and residential hub.

It is this very evolution—plus its transportation network—that makes the neighborhood ideal for Amazon’s second headquarters in North America, Lower Manhattan boosters say.

Amazon wants 500,000 square feet of office space in 2018 with another 7.5 million square feet over time. And Lower Manhattan has the potential for over 8.5 million square feet of space, according to the city’s recent proposal to Amazon.

Granted, Downtown Manhattan would not be the cheapest option nationwide. But, “cost of space should be least of their concerns,” Marty Burger, the chief executive officer of Silverstein Properties, said in a survey for Commercial Observer’s upcoming Owners Magazine. (The landlord owns the majority of the World Trade Center buildings.)

“Most important is access to new talent,” he continued. “You want a place that has A) the best transportation, B) a great pool of people to draw from. When we look at the lower tip of Manhattan, it has the best access to all this talent—Brooklyn, Queens, Staten Island, Jersey City, even Long Island. There are 10 million people to draw that talent from.”

Lower Manhattan has a high concentration of mass transit with 13 subway lines and the PATH train, and those transit hubs have been upgraded with abundant retail and dining options as well as climate-controlled concourses, said John Wheeler, a managing director who runs JLL’s Lower Manhattan office.

Downtown Manhattan boasts access to the waterfront, more than 83 acres of open space and enticing dining options, from food halls like Hudson Eats in Brookfield Place to restaurants helmed by star chefs, like Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Nobuyuki “Nobu” Matsuhisa and Danny Meyer, to fast-casual chains like Chop’t Creative Salad Company and Dig Inn.

Burger has already figured out how to make it work for what’s being called Amazon HQ2.

“We could put together a campus for them,” Burger said. “They could take the top of 3 World Trade Center. We could work with Durst [Organization] to get them the top of 1 World Trade Center. We have a potential to build 2 World Trade Center and 5 World Trade Center. We could put together 7 million square feet.”

But there are also other options for Amazon.

Wheeler noted that, while the World Trade Center would be “part of the solution,” other candidates include Brookfield Place, 28 Liberty Street and Guardian Life Insurance Company of America’s headquarters building at 7 Hanover Square.

—Lauren Elkies Schram

Long Island City

Long Island City’s relatively recent transformation from an industrial outpost to Queens waterfront hotspot has been mostly fueled by residential development, with more than 14,000 new units built since 2006 and another 19,000-plus in the pipeline, according to data from the Long Island City Partnership.

As far as commercial development is concerned, however, the neighborhood by most accounts has some way to go. Most of Long Island City’s new office stock has come in the form of repositioning existing warehouse buildings into loft-like spaces mostly of a scale smaller than what Amazon would demand.

But the city is floating LIC as a legitimate option for Amazon, citing the neighborhood’s “creative” appeal as “home to over 150 restaurants, bars and cafés” and more than 40 “arts and cultural institutions” including galleries, museums and theaters, according to the NYCEDC’s proposal.

While the proposal cites “over 13 million square feet of first-class real estate” available in the neighborhood, how much of that qualifies as office space that would suit Amazon’s needs is murkier. Per the LIC Partnership, the area has roughly 7.5 million square feet of existing, nonretail commercial space—which would already fall short of the 8 million that Amazon will eventually require—and another 4.5 million square feet on the way by 2020.

But projects like The Jacx—Tishman Speyer’s two-towered development that promises to bring 1.2 million square feet of Class A office and retail space to Jackson Avenue—hope to further enhance the neighborhood’s office chops. And perhaps the biggest advantage LIC has is its relative affordability compared to the other areas under consideration with the city citing “price points that compare favorably with commercial centers across the five boroughs.”

For developers like TF Cornerstone, which was an early believer in Long Island City and has helped facilitate its transformation via multiple large-scale residential projects, Amazon’s arrival would be a massive boon to the neighborhood’s economy—one that would fuel demand for the thousands of new residential units due to come online, attract needed retail to the area and heighten its profile as an office destination. In turn, LIC’s relatively central location within the five boroughs and robust public transit offerings would give Amazon what it needs for a viable HQ2.

“The north Long Island City waterfront offers the best location for a large user like Amazon,” Jake Elghanayan, a senior vice president at TF Cornerstone, told Commercial Observer in a forthcoming interview for Commercial Observer’s Owners Magazine. Elghanayan cited the neighborhood’s large “contiguous development area” and robust public transit offerings, as well as its proximity to the new Cornell Tech campus on Roosevelt Island.—Rey Mashayekhi

West Side of Manhattan

Those associated with the Hudson Yards megaproject like to say that “a new city” is being built on Manhattan’s Far West Side, and it’s hard to argue with the assessment. With tens of millions of square feet of new commercial space due to come online in the area over the coming years, Hudson Yards would most likely serve as the centerpiece of the city’s effort to get Amazon to commit HQ2 to Manhattan’s West Side.

Besides the sprawling 28-acre development being undertaken by Related Companies and Oxford Properties, there is also Brookfield Property Partners’ Manhattan West project nearby, where Amazon already has a sizable footprint. Last month, the tech giant committed to taking 360,000 square feet of office space at 5 Manhattan West, where it will house 2,000 employees and serve as the primary location for Amazon’s advertising division. (CO first reported that Amazon was in talks for the space in April.)

The city’s proposal for HQ2 also cites the nearby Penn Plaza district, where Vornado Realty Trust—the largest commercial landlord in the area surrounding Penn Station—has in recent years talked up a large-scale repositioning of its assets in a bid to capitalize on the West Side’s newfound appeal as an office destination.

In total, the city says the West Side offers Amazon more than 26 million feet of available office space to build its campus—more than triple the 8 million Amazon will need long term—as well as ample transit options for the company’s sizable workforce: 15 subway lines, plus access to the PATH, the Long Island Rail Road, the Metro-North Railroad and Amtrak, not to mention the Port Authority Bus Terminal and the Hudson River ferry service.

But the West Side could prove cost prohibitive; it is the most expensive of the four New York City submarkets being floated as options for Amazon. With the cost of living and doing business in New York already the biggest drawback in the city’s bid for HQ2, the likes of Related and Brookfield may have to look elsewhere to fill up all that office space.

Such cost concerns aren’t discouraging neighborhood stakeholders, however. “Manhattan’s always been expensive, but it gives you other things,” said Robert Benfatto, the president of the Hudson Yards/Hell’s Kitchen Alliance Business Improvement District. “It has its upsides and downsides, but it tends to be attractive to businesses.”—R.M.

Downtown Brooklyn

Out of the four neighborhoods New York City proposed for Amazon’s second headquarters, the “Brooklyn Tech Triangle” of Dumbo, Downtown Brooklyn and the Navy Yard might hold the most promise. Although the area doesn’t have much office space right now, several large projects are either under construction or in the pipeline. At the Navy Yard, Rudin Management and Boston Properties’ Dock 72 will bring 675,000 square feet of offices—anchored with a 222,000-square-foot WeWork—to a former dry dock on the East River.

Besides Dock 72, landlord Brooklyn Navy Yard Economic Development Corporation is leasing up a newly renovated 1-million-square-foot industrial and office building called Building 77, and there’s available space at Steiner Studios, the film and television production complex on the eastern edge of the yard. The closest subway stations are about a mile away in Dumbo (certainly its biggest drawback), but the yard has begun running shuttle buses that take commuters into Dumbo and Downtown Brooklyn for easy transit access. It’s also about to open a new ferry stop next to Dock 72.

TerraCRG Founder Ofer Cohen dispelled concerns about the Navy Yard’s lack of transit, pointing out that it hasn’t prevented hip companies from setting up shop there. New Lab, an innovative science and tech coworking space, recently opened in Building 128. And Building 77 hosts tenants like startup incubator 1776, a commissary kitchen for small food manufacturers called Tiny Drumsticks and fashion company Lafayette 148. He noted that Dock 72 would probably be the only project large enough to accommodate Amazon’s requirement of 500,000 square feet of office space in 2019.

“Downtown Brooklyn and the Brooklyn Tech Triangle are poised for significant growth,” said Downtown Brooklyn Partnership President Regina Myer. “There’s a huge demand for Class A space in Downtown Brooklyn. We have 1,400 innovative companies in the broader tech triangle. And we have an amazing pipeline of new talent for companies relocating to the tech triangle because we have 10 different colleges.”

Myer pointed to several sites in Downtown Brooklyn that could host Amazon. Rabsky Group could build an office building as large as 770,000 square feet on its vacant parcel at 625 Fulton Street, and RedSky Capital could develop a huge commercial and residential project on its assemblage bounded by Dekalb Avenue, Flatbush Avenue and Fulton Street. And Tishman Speyer is developing the Wheeler, a 10-story office building, on top of the Art Deco Macy’s department store at 422 Fulton Street.

CPEX Real Estate’s Timothy King, the brokerage’s managing partner, pointed out that Amazon would have convenient access to plenty of retail and amenities in Downtown Brooklyn, including hospitals, hotels, shopping, restaurants and bars. And when you consider Atlantic Terminal, the broader tech triangle offers 13 subway lines. “Short of going out in the desert somewhere and building some kind of utopian village,” he said, “I’d be hard pressed to find some place better for Amazon than beautiful Downtown Brooklyn.”—Rebecca Baird-Remba