What Office Landlords Spend on Amenities to Draw Tenants

Office landlords are laying out real money and trading valuable floor space to include doggy day cares, golf simulators and other features to entice quality tenants

By Celia Young April 18, 2022 9:00 am

reprints

Landlords and employers are spending more money to draw staffers from their home hidey-holes — as those same workers are questioning the need for a company office altogether.

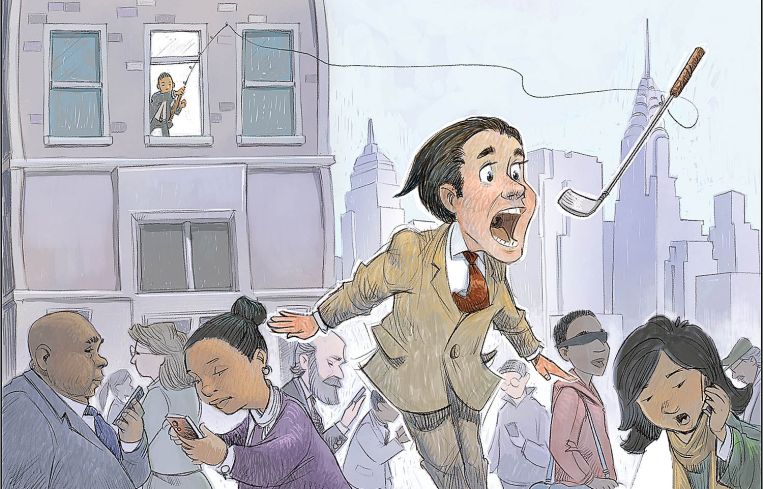

At the start of the pandemic property owners were spending on HVAC systems, cleaning supplies and signs directing people away from high-touch surfaces and each other. Today it’s the more unconventional amenities’ time to shine — doggie day cares, beehives, grab-and-go cafes and golf simulators among them. But the perk gold rush comes at a price — and a high one for full-floor amenity spaces.

A not-so-shocking byproduct of remote work is that staffers need a lot more convincing to get back in their cubicles — that is, if they ever plan to return at all. With 61 percent of workers surveyed in February choosing to stay home when they have the option, amenities and perks have become integral to the modern, pandemic office as a result, said Jonathan Bennett, president of AmTrust Real Estate.

“The same way you have to have a boiler to provide for the building, you have to have these amenities as well,” Bennett, who oversees 12 million square feet of office properties across cities like New York and Chicago, said. “It’s become essential.”

The amenities arms race started before the coronavirus was a part of our shared vocabulary, but the pandemic has brought it into sharper relief. The actual cost of lures for office workers — like a putting green or a parking subsidy — is fairly low for landlords and tenants alike, but the cost of potential lost rent on the space itself is far from negligible.

One such example is the real estate firm that opened a dog day care for its tenants — in direct response to the pandemic puppy boom, where people rushed to find furry friends in the absence of human ones. (It’s worth noting that not everyone kept their new pets, and shelters struggled to take in a higher number of cats and dogs last year.)

For those that didn’t give up their new dogs for adoption, the firm had a solution: 2,000 square feet of previously unused space transformed into a place for dogs with a hired caretaker that watches about 12 to 15 pups for six hours a day.

The company is a client of Robert Gilman, the co-leader of the real estate services group at the accounting advisory firm Anchin, who couldn’t identify his customers but shared specifics on their spending habits. Gilman advises property owners in Manhattan and the tri-state area in the office, multifamily, studio and storage sectors, and has several clients giving the amenity game a shot.

The canine day care facility cost about $20,000 to install, including with renovations to the space and supplies like cages and fences, and about $300 a day to staff, Gilman said. To a large corporation, dropping $20,000 on rent and $100,000 or so on staffing costs for the year, while not insignificant, is not a huge expense. For example, Prologis (PLD), which holds a 1 billion-square-foot portfolio, spent between $300 million and $315 million on general and administrative expenses, according to public disclosures, and SL Green (SLG) Realty Corp. spent $747 million in 2021 for all of the firm’s expenses and nearly $100 million on marketing and administrative costs.

But what landlords lose when a firm adds an amenity space is the potential income from renters. Gilman gave the example of 5 Times Square — not one of his clients, but an RXR property with a 48,000-square-foot amenity floor equipped with fitness center, lecture hall, restaurant and lounge. The real estate giant spent $50 million renovating the amenity space, lobby, elevators and more in 2020. With asking rents in a recent deal there for Roku in the $90s per square foot, the cost of such a large amenity floor is far from negligible.

Even if RXR charged just $50 per square foot for the floor, the firm could rake in more than $2 million per year in renting out the space. But firms with large amenity spaces like RXR’s are likely pulling in at least $20 to $30 per square foot more thanks to its amenity spaces, according to Richard Jantz, executive managing director of project and development services at Cushman & Wakefield (CWK).

“I couldn’t even tell you what 5 Times Square spent on their amenity space,” Gilman said. “They must have spent several million dollars, but remember, they also have conference room space, which was part of their hook to get people in there.”

RXR wouldn’t say what it spent either, but the real estate giant talked about the importance of amenity spaces more broadly. The amenities RXR has rolled out at the Starrett-Lehigh building — beehives on its rooftop, an exhibit from renowned artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, a 40,000-square-foot amenity space — are crucial features of its portfolio; the pandemic just made that even clearer, William Elder, RXR’s executive vice president and managing director of New York City, said.

“The war for amenities is on right now,” Elder said. “These are not cheap projects, but it adds value to the asset. … If you don’t have these things, you’re not even on a tour.”

Amenity floors can buoy asking rents, encourage existing renters to renew and attract other tenants — something more important than ever in the age of remote work. Shared amenity space can even be built into a lease agreement, increasing a tenant’s rentable square feet without actually increasing a tenant’s individual square footage, Wendy Feldman Block, a Savills executive managing director, said.

Without those amenities, a building is no doubt at risk of losing tenants, Jantz said. Those investments, even the costly ones, help attract tenants and raise rents, he added. With higher-quality, amenity-ridden space being the clear winner of the pandemic-stricken office market, property owners may be forced to invest in perks just to get someone to sign on the dotted line.

“Twenty or $30,000 — that you could always find in a deal,” Gilman said. “It’s not like [knocking] out a floor that you’re going to rent and do a full amenity space, so not only are you spending a couple of million dollars but you’re losing that rent.”

Basically, bigger might not always mean better. But bigger might be the only way to entice office workers back to an in-person setting. And, so far, it seems to be working, according to Peter Trivelas, an executive managing director at Cushman & Wakefield. He listed two examples, 2 Park Avenue and 545 Madison Avenue — both buildings with generous amenity spaces and lounges already built or on the way.

The Park Avenue property, between East 32nd and East 33rd streets, has a 7,000-square-foot full-floor lounge on the 27th floor with a billiards table, a cafe and lounge style seating — previously plug-and-play office space. Over on Madison Avenue, the 17-story building will have an eighth-floor amenity space on part of the floor with a “signature scent,” said Trivelas. (The smell was created by the owner, Marx Realty, and rolled out first at 10 Grand Central before the pandemic began, through Trivelas stopped short of describing what it smelled like. Apparently it includes “leather and wood scents with a touch of jasmine and lemon,” according to Marx President and CEO Craig Deitelzweig.)

Both spaces were key for tenants to sign leases — in fact, tenants wanted assurances that the spaces would be completed before committing to deals, Trivelas said.

“There is no doubt in my mind that there’s a strong correlation between the success we’ve seen and the amenities,” Trivelas said.

Of course there are other, less expensive ways to get people in the door without sacrificing so much rentable space. Another one of Gilman’s landlord clients is considering buying a golf simulator for about $35,000, which takes up only around 200 to 500 square feet. Cushman & Wakefield happens to have installed a putting green in one of the firm’s conference rooms in its New Jersey office, though it was more because the firm had the extra space and the $2,000 to install it than anything else, Jantz said.

Project Management Advisors (PMA), a real estate advisory and owners representative firm, tried to address lingering fears over taking public transportation due to the airborne virus — which inspired a huge boom in used car sales in 2020. The firm created a free parking reimbursement program for its employees in Los Angeles, Boston and Chicago, spending less than $10,000 between May and December 2020, Roger McCarron, president and CEO of PMA, said.

Another of Gilman’s clients installed a miniature cafe, where ownership purchases about $500 of sandwiches per day from a local deli and then sells the food to tenants. The one-time cost of the installation was only a few hundred dollars and the firm only loses another few hundred on the sandwiches it fails to sell each day. All in all, Gilman said, it’s a fairly negligible sum.

Terraces became extremely popular as well — because open-air spaces tend to be safer when it comes to airborne diseases and because rooftops aren’t usually selling space, meaning a landlord isn’t losing potential income from renting them. One of Gilman’s clients spent around $40,000 to renovate a rooftop with a new concrete floor and furniture — with no lost rental income.

But landlords might want to limit their expectations — even with all this spending, said Feldman Block. With a clear preference among workers for flexibility, if not staying remote altogether, New York City might never completely go back to the pre-pandemic office norm.

Still, landlords, particularly larger landlords of higher class, newer buildings, will need to invest regardless to keep up with the fierce competition, Jantz said. Giving up on office, for someone in the attached landlord business, is not really an option.

“There’ll always, always be a cross-section of people that say, ‘I just want the cheapest rent. I have to be in New York City [and] I don’t care what it has [or] where it is,’” Jantz said. “But the majority of people are looking to use this as a marketing tool to get people in their offices. … Is a building at risk of losing a tenant because they don’t have amenities? Without a doubt. Without a doubt.”

Sometimes you’ve got to spend money to make money. And sometimes you’ve got to spend money to convince everyone that you’re still relevant.