What Fuels the Northeast’s Life Sciences Industry

For one thing, the usual rivalries don't apply

By David M. Levitt September 23, 2021 8:35 am

reprints

A lab worker draws a blue fluid through a multi-prong blotter into a multitude of cups. Out of the experiment could come drug discoveries that might help with cancer or some other disease.

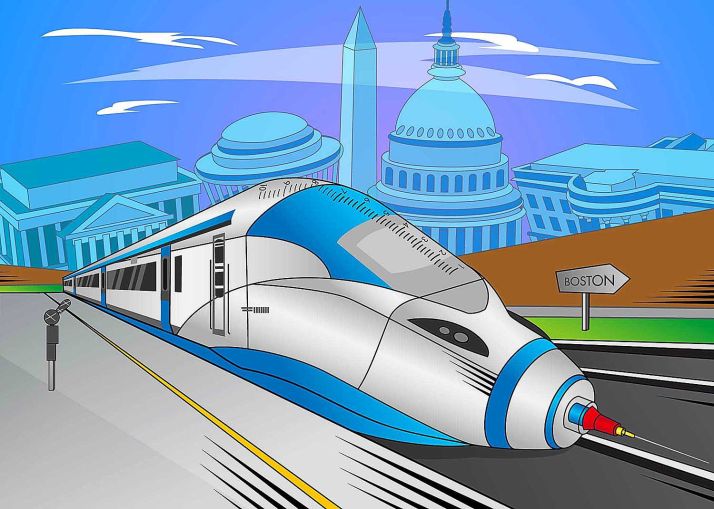

This is the Winchester Works in New Haven, Conn., a stone’s throw from Yale University. It’s a relatively new piece of a long ecosystem that stretches from the labs of East Cambridge, just northwest of Boston, the entire 450 miles down to the halls of the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration in Washington.

Life sciences, often called bioscience, or the study of ways to fight disease and help people live longer and more energetic lives, has become a dominant obsession in both real estate and city halls across the country, as local officials look for ways to add a new and growing sector to their local economies. The battle has taken on a new sense of urgency with the rise of the coronavirus, and the emptying out of cities, like New York, reliant on finance and other office-using industries. Hardly anyone is going to conduct experiments at home when they have a laboratory at their disposal.

But, from the perspective of life sciences entrepreneurs, it’s less important for an individual city to have all the support a growing life sciences company needs than for such things to be accessible in general.

It’s not a border war. It’s not New York vs. Boston vs. Philly vs. New Haven, or what have you. It’s the entire Northeast corridor, from Boston/Cambridge down to the D.C. area, all doing their part, all working together in providing bioscience businesses what they need to thrive.

“It’s really both,” said Brendan Carroll, director of Boston research and Americas life sciences for brokerage Cushman & Wakefield (CWK), and co-author of “Life Sciences on the Rise: North American Report”, a C&W study released in June. “Companies, for the most part, are really connected to one specific region, and within that region, they work really hard to find the right specific location.”

Still, with investors most comfortable and informed about market developments in densely settled regions with large life sciences industries, like Boston and New York, he said these providers “can quickly access the centers of cities elsewhere in the corridor.

“The other, and potentially more compelling, driver may be that scientific competency, to date, has been something that has accumulated over time, requires investment, and has become increasingly collaborative, especially as products become more complex. The pedigree, the capital and the dense settlement of institutions in the Northeast corridor may make these places inherently attractive in today’s biotech world.”

Boston — fed by some of the brainiest idea generators in the world, Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology — has created critical mass for some of the most ambitious life sciences companies in the U.S. According to Cushman & Wakefield’s study, 27 percent of the $70 billion invested in life sciences between 2020 and April 2021 was earmarked for Boston-area companies. New Haven has Yale University and inexpensive lab space where companies can get started and get through the early phases.

New York has Wall Street and an almost uncountable number of companies looking to finance the next big thing or, perhaps even more importantly, willing to finance those who will try and not succeed to make the next big thing. New York also hosts its own cluster of life sciences companies in Manhattan, Brooklyn’s Industry City and Queens’ Long Island City.

Long Island City was lagging in its life sciences development as recently as five years ago, said Liz Lusskin, president of Long Island City Partnership, a development organization. But when it pressed the matter with leaders in the industry, the answer it got back was, “It has to happen,” she said. That was because the industry was growing so fast that it needed places for incubators and where startups can happen, she said.

New Jersey has a well-developed, traditional pharmaceutical research and development sector with well-known names like Merck, Bayer, Johnson & Johnson, and Bristol Myers Squibb, as well as thousands of people who have both the intelligence and the experience to help bioscience startups get off the ground. Philadelphia, while nowhere near as built out as Boston, New York and Washington, has its own developing life sciences scene. Leading the way is a 250,000-square-foot, eight-story lab and office building backed by Silverstein Properties and Cantor Fitzgerald that’s supposed to be done in 2022.

And D.C. has regulatory agencies, such as the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration, which oversee and help fund all of that research and development, and issue the coveted permits that enable a product to be sold. The wider Washington area also has its own burgeoning, private life sciences industry.

No, other life sciences clusters, such as the San Francisco Bay Area and San Diego, are not going away. But the Northeast life sciences corridor can be just as important to the development of the industry as anywhere else, and maybe more so.

The lab worker described at the start of this article works for a company called Halda Therapeutics, an ambitious life sciences startup, which, like a number in the New Haven area, was co-founded by Craig Crews, the John C. Malone professor of molecular, cellular and developmental biology at Yale.

Scott Phillips, Halda’s chief financial officer, said it rented about 9,800 square feet at Winchester Works, and moved in early this year. It has about 20 employees and should double that number in the next two to three years. It expects to eventually outgrow Winchester, but it has not decided where it will move next, Phillips said.

The city has a contract with a company called Winstanley Enterprises to build a 525,000-square-foot bioscience lab and office building in Downtown New Haven at 101 College Street. Yale has agreed to be its anchor tenant.

Being on the corridor helps, Phillips said, “primarily from a recruitment of talent perspective. We have hired a few people from the New York market. You might have someone who may be in Fairfield County, and whose spouse works in New York. That’s definitely a positive.”

Winchester Works, part of a historic district, is so named because it is on the grounds of the old Winchester gun factory from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The slabs are so permeated by the oils that were used to make the guns that the main factory buildings can’t be salvaged and must be razed, said Jake Pine, a director of L+M Development Partners of New York, whose partnership operating the site includes Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group and Twining Properties. He is overseeing construction, leasing and management for the developers on the site.

“We are trying to create a 24/7 campus here that will be ‘live, work and play’, to use a much-overused phrase,” Pine said.

The site, when fully built, should have about 1,000 apartments, retail space, and about half a million square feet of office and lab space.

It can be costly to build life sciences space, as developers who’ve tried already know. Daniel Hackett, Cushman & Wakefield’s Eastern region life sciences lead, and an adviser who real estate leaders turn to for guidance through the ins and outs of such development, said energy costs can average two to five times the cost of climate-controlling conventional offices, and constructing a simple analytical lab two to three times your typical office.

Another part of the Winchester Works complex, Science Park 4 and 5, across a parking lot from L+M’s property, is home to labs and offices for Arvinas (pronounced “ar-vinnis” with the accent on the “ar”), which describes its mission on its website as nothing less than “leading the creation of an entirely new way to treat disease through therapies that target and degrade disease-related proteins,” targeting cancer, particularly prostate and breast cancers. The therapies have resulted in the shrinkage of some tumors.

Arvinas’ Chief Financial Officer, Sean Cassidy, said it was also the brainchild of Crews, and rents about 3,500 square feet at Science Park 4, where it originated and had about 25 people in 2014. It has about 60,000 square feet at Science Park 5.

Arvinas has since formed partnerships with Bayer, Genentech and Pfizer to further develop its platform.

“This year, we are going to end up with somewhere around 280 people,” Cassidy said. The company has continued to add space at Science Park 5 — 4 and 5 are owned by the Science Park Development Corp. (SPDC), a nonprofit established by Yale, the City of New Haven, the State of Connecticut and the Olin Corp.

L+M is working with SPDC “to realize the larger vision for Winchester Works,” Pine said. L+M ground-leases its property at the complex, he said.

“Is the Northeast Corridor a biotech life sciences hub? No doubt about it,” Cassidy added. “Look at the Boston market all the way down to New York — that’s probably the biggest life sciences market that there is in the country.”

Funding flowing into the biotech industry is accruing to the benefit of Arvinas, and the company continued to hire when other businesses all but shut down due to the virus, Cassidy said. The company actually doesn’t have enough seats for all of the employees it has hired. It shut down non-lab office space, which represents about half of what it rents at Winchester, and has continued to keep them closed with the rise of the delta variant.

We “continue to participate in a hybrid model of work,” Cassidy said. “For Arvinas, [that] means lab employees will primarily remain on-site, and a portion of our employee base will remain remote.” Remote work “has worked well for us,” he added. Arvinas has plans to open up at 101 College, and will continue the hybrid model when it does, he said.

Lauren Gilchrist, managing director of research for Longfellow Real Estate Partners, which builds and operates labs both inside and beyond the corridor, including on the West Coast and in North Carolina’s Research Triangle, said “it’s the nature of the Eastern Seaboard” to be conducive to life science.

Closely held Longfellow boasts on its website: “We’ll create the space. You bring the science.”

“It’s bookended by these two massive forces,” Gilchrist said of the corridor. “Boston has one of the most dense clusters of life sciences anywhere on the planet. It’s really the top life sciences market in the world. And, on the other end, you have NIH, the FDA. And, in between, it’s soup to nuts.”