WeWork Documentary Director on Adam Neumann’s Downfall, Massive $47B Valuation

Jed Rothstein directed Hulu's "WeWork: Or The Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn."

By Chava Gourarie March 24, 2021 4:34 pm

reprints

At one point in WeWork’s time as the darling unicorn of Silicon Valley, it was hiring more than 50 people a week. On Mondays, the new employees would attend an orientation that schooled them on the mythology of WeWork. Afterwards, they would chant, “We. Work. We. Work. We. Work.”

It was part of the cult-like environment that the overhyped and overvalued WeWork engendered, as it chased growth at all costs, burned through money while it claimed to be profitable, and sold itself as a transformative and extremely valuable force.

In “WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn,” a new documentary about the office-sharing startup, director Jed Rothstein charts the arc of the company: how it went from young startup to millennial trendsetter, to Manhattan’s largest landlord, and ultimately, after its disastrous initial public offering (IPO) effort, to a humbled shadow of its former self. The documentary premiered at South by Southwest (SXSW) earlier this month and will be available on Hulu on April 2.

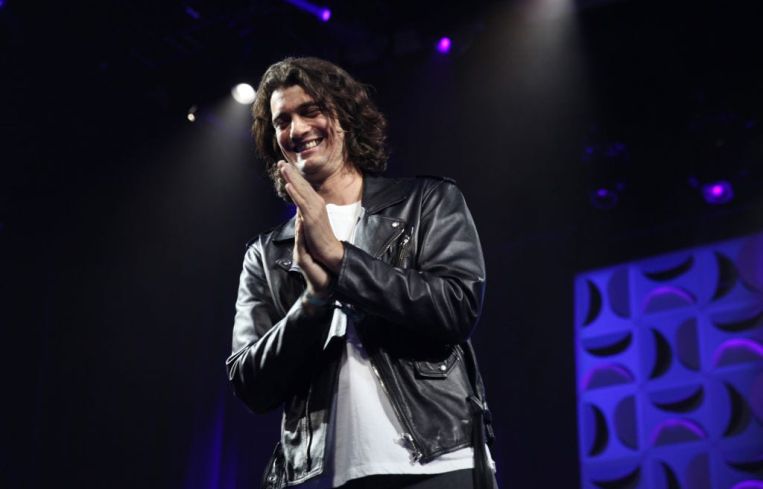

Of course, the WeWork saga is the story of former CEO Adam Neumann, the charismatic, Israeli-born immigrant who led the company’s growth and downfall, along with his own. Neumann founded the company with Miguel McKelvey in 2008, with the idea of chopping up office spaces and selling them by the desk. Both he and McKelvey had grown up on communes on opposite sides of the world — Neumann on an Israeli kibbutz and McKelvey in a women-led commune in Oregon — and wanted to recreate the community aspect of the commune, minus the socialism.

The story of WeWork is fairly well-trodden because of all the real-time coverage, one book already published and another on the way. Where the film shines is in its use of extensive footage of Neumann, which starts off invigorating, and eventually becomes draining as disillusionment sets in. The documentary frames the rise and fall well, offers insightful (and, sometimes, enraging) interviews with insiders at WeWork, and highlights the employees that were hurt by believing in a vision that was so much air. What it doesn’t necessarily offer is significant insight into the question of how Neumann managed to pull it off. Despite showcasing how charismatic, convincing, and possibly manipulative Neumann could be, it isn’t enough to explain how he managed to bend the world to his vision for a decade — until its first contact with reality.

Commercial Observer spoke with director Jed Rothstein, who previously directed “The China Hustle” and “Killing in the Name,” about the making of the film, the layers of the WeWork story, and what it was like to film during COVID-19. The following is an edited version of the conversation.

Commercial Observer: Why did you choose to tell the story of WeWork?

Jed Rothstein: I was very excited to do a New York story, a story that I think has in its bones this kind of financial mystery, but also is about something a lot deeper — which is how can we form the way that people spend so much of their time, because a lot of the institutions and groups that people used to be part of are no longer here. People move around companies a lot, so these types of communities that people used to form weren’t there for them, and I think that coworking in general is an interesting way to try and create some of this community in a time where it’s largely absent. So, I was interested in both the wild financial ride, WeWork starting and being bid up to $47 billion, and then collapsing so rapidly.

Have you ever met Adam Neumann?

No. I tried pretty strenuously to get him into the film, to meet with him and [his wife] Rebekah [Neumann], but they wouldn’t.

You open with footage of Adam filming a speech for the IPO roadshow, and it’s not going well. Adam is fumbling over the words, and while he continues joking around, it’s clear he’s frustrated. Later, you reveal that despite a whole day of shooting, Adam couldn’t pull it off and it was left out of the presentation. Why did you open with that?

I think that it was in the absence of having Adam sit down with us, I knew that the film was going to include a lot of archival footage. I knew that WeWork had filmed a lot and filmed all sorts of documentaries all the time. And, more importantly, that people within the WeWork community had generated an enormous amount of social media content. I actually thought this was a really attractive way to tell the story, because it’s this story of a community of people, [but] it’s also a story about a company that is creating a narrative for itself. So, picking through that material to create this narrative visual to what happened seemed like a great way to tell the story.

And because Adam was so often “on” — meaning [that], when he was on camera, he was performing so much of the time — I thought it was really important to show right up front that we were going to look at him from a different angle. So, having something that hadn’t gone out, and where he was not performing in the way that he hoped to perform, to me was a way to open up with the type of intimacy that you’d want to have with the person who’s at the center of the story.

The documentary is ostensibly about WeWork’s rise and fall, but the actual film is essentially the story of Adam Neumann. Is there any other way to tell the story of WeWork but to tell the story of Adam?

One of our characters at the end of the film says that it’s kind of a shame to focus the story on Adam, because it overlooks the work of so many others. I do feel it’s important to look at both sides. I mean, Adam was the charismatic face of the company. He and Miguel founded it together, but Adam was much more of the sort of front-of-the-room guy. And, as the company grew into a much bigger and bigger business, I think Adam was more involved with that side. So, while I think it’s important to emphasize all of the other people — both for the workers at WeWork, the members, of course Miguel and some of the other senior executives — it’s important to emphasize their role. But, at the end of the day, I don’t know how you would tell the story of WeWork without Adam pretty centrally focused.

The million-dollar question in a lot of these kinds of stories — about very charismatic, visionary figures who take people on a ride that ends up imploding — is usually: Did they believe their own vision or are they conmen? Is that the question at the heart of this story, and do you have an answer for it?

I’m always attracted to stories that have some nuance and gray area. That maybe is not always popular. I think it’s easier to make a film where you just say, “We’re unmasking this terrible villain and here they are.” I don’t think that’s the case here. I think Adam stepped into a tradition, a great New York tradition, of hustling, and he came up with the idea of WeWork and latched on to it, to pursue it seriously. Did he believe all the promises he made to some of his young workers that they were going to be millionaires? I don’t know if he believed those or not. Did he believe some of his grand pronouncements about curing the world of orphans, and some of these enormous global problems that he said they were going to tackle? I don’t know.

But he did want to create something new and different. And he did create something new and different. But, at the end of the day, when it became this very high-stakes financial game, some of the pronouncements he was making turned out to be clearly false. And my guess is that he knew some of those things he was saying that were not true would become problematic as they marched through the IPO process. So, I think it’s somewhere in the middle. My sense is that he did believe some of it; he did have some intentions that were good. And he also maybe believed too much of it, in a way. Maybe that’s the way to look at it. He believed too much of his own hype. And because of that, he wasn’t cautious enough when he ventured too far away from the hard facts.

The first act of the film, which focuses on WeWork as a young startup, highlights how the company did disrupt the office culture of the time — and even though there were Facebook and Google campuses and the like that were changing the millennial workplace — WeWork had a huge role to play in advancing an alternative to corporate office culture.

They’re nice places. There are things about it that one could like or not like, but compared to what was there … They did it on scale and they did have nice places, and they located them in nice spots, and the flexibility thing for a small businessperson is a big deal. I used to sign these long leases and it was scary, because you don’t know if you’re even going to be around in 12 months. That side of it, I think, will stick around, whether WeWork succeeds at it or other companies do. I think that the idea of well-managed and pleasant-to-be-in coworking spaces, I’m sure it’s here to stay.

Obviously, the throughline in the story of WeWork is what they said they were doing and what they were actually doing. There’s endless footage of Adam talking about changing the world and creating community, and changing the way people work and live. And then, you have the economist, Scott Galloway, who says, “For god’s sake, they’re renting fucking desks.” After producing this film, do you have an answer for how they were able to sell themselves as something transformative, and potentially worth tens of billions of dollars, when it was so far from the business they were actually running?

The thing that got them in the most trouble at the end, financially, in terms of their valuation, is they kept insisting, and Adam especially kept insisting, that they were a tech company. Tech companies, because of the dynamics of creating and selling technology, tend to have much higher valuations, say 10x [of revenue]. And real estate companies, as we talked about in the film, have much steadier and lower multiples. So, if you say you’re a tech company, investors can assume that you’re going to be, even if you’re not making money now, you’re gonna be making a lot more money later. And therefore, your prospective valuation can be much higher. If you’re a real estate company, where each additional unit requires you renting more real estate and hiring more people and more spacing, your ability to hit some kind of inflection point, where your growth just becomes astronomical, is much more constrained.

Part of it was maybe they believed in the spiritual side of what they were selling, but another part of it was if they sold themselves as a transformative tech company, they could sell the idea that their valuation would explode much more dramatically than it would if they were in real estate. And I think when they ultimately went public, the public’s reaction was, “Well, no, you are a real estate company and, therefore, this valuation is crazy. Because we don’t see how you could ever achieve the underlying profitability that you’re talking about that would make this valuation make sense.”

The movie dedicated some time to the role of Adam’s wife, Rebekah, who is a lesser known figure in the saga of WeWork, but who definitely appears to have shaped some of WeWork’s more questionable projects. Why did you choose to highlight her involvement?

I noticed that in the founding mythology of the company evolved from Adam and Miguel, two guys who have grown up, at least partly in the commune, who wanted to create this kind of office commune or capitalist office kibbutz. That evolved into there having been three founders, and Rebekah became woven into that story in their retelling of it later in the life of WeWork.

I thought that that was interesting, so we looked backwards to try and determine when and how that happened, and what role she had played early on. She played a very big role in shaping Adam’s thinking about WeWork, shaping his thinking about some of the more spiritual aspects in the company. And he highlighted that a lot. And, at a certain point, the company began to expand in direction that embraced that, and put real money behind it. WeGrow [its pricey, private school] was a big part of that. That was a project that she was instrumental in. A lot of people felt that taking on these types of non-core enterprises were a big part of the problem, or the beginning of them getting into a lot of problematic things, and got them into [the] pickle that they were in when they tried to go public. And the public didn’t want to buy or, at least, not at the price they were selling.

You start to hear Adam talk more about elevating consciousness later on, whereas earlier, he would have just said something like making the world a better place or changing the world. It’s like his language changed to become more spiritual.

That goes to your earlier question at the hype. I think, probably, he did believe it too much. Because at a certain point, he was talking about elevating consciousness, and changing the way people work and live, and go to school and do everything else. And when you have to publish an S-1 [an IPO form detailing a companies’ financial], the people who are going to buy this or not are not, by and large, people who care about a lot of these spiritual questions. They just want to see how much money you’re spending and how much money you’re making. And if you let yourself get too caught up, when you have to show all your cards, it can be a pretty tough reckoning. And it really was for them.

The documentary was filmed during COVID. How did that affect the story you told and how you told it?

Yeah, the entire film was made during COVID. We did a lot of archival work first, and started shooting only when that really became possible. There were certain people who probably would have come out and filmed with us in normal time, but weren’t willing to. Our attitude was, of course, number one, be safe. Number two, be respectful of people’s own feelings about COVID. And number three is get the people who are willing to do it and press onward, because otherwise, we wouldn’t have been able to tell the story and we would effectively still be sitting around now waiting for things to go back to normal.

The other thing I would say is that it was very nourishing, and my crew and I are very lucky to be able to work and make a movie throughout this.