Manhattan Office Demand Won’t Reach Pre-COVID Levels Until 2023

Vacancy could spike to levels not seen since the mid-1990s

By Tom Acitelli February 12, 2021 7:00 am

reprints

Buckle up. Despite an uptick in activity at the beginning of 2021, analysts don’t expect the Manhattan office market to recover to where it was pre-COVID until at least 2023.

That’s right: This year and next are a limbo of uncertainty.

The numbers coming into 2021 were promising, from a landlord and landlord/broker perspective, but not particularly sunny.

Leasing activity totaled 1.9 million square feet in January, the highest volume since July 2020, according to a Colliers International report that tracked Midtown, Midtown South and Downtown. That also represented an 18.6 percent increase from December, and was 20.3 percent higher than the monthly average — 1.58 million square feet — in the terrible year of 2020.

But it was still nearly 47 percent below the 2019 monthly average of 3.58 million square feet. That was, of course, before the pandemic’s stay-at-home health advisories emptied offices throughout America’s premier office market, and sent the volume of available sublease space soaring and asking rents tumbling.

The average asking rent for Manhattan office space, in fact, dropped for the seventh straight month in January, to $73.65 a square foot — the lowest average since April 2018. The average asking rent has decreased 7.3 percent since the start of the pandemic in March, according to Colliers International.

And that sublease space? The volume of such available space, depending on which measure one uses, has long been flirting with share levels not seen since the dot-com-bust-slash-recession at the start of the century, never mind the Great Recession of 2008 and 2009.

A report from brokerage Savills pegged the volume of sublease space at 18.6 million square feet by the end of the fourth quarter of 2020, the highest this century. That also represented a share of 27.2 percent of the available market, just shy of a share peak of around 30.3 percent in 2009.

Overall, the Colliers International report had the market’s availability rate at an all-time high of nearly 15 percent. That doesn’t include the companies not having their employees come into the office—which remains a lot.

As New York City approaches the one-year mark next month of grappling with COVID, most of Manhattan’s offices remain empty during any given workday. That reality will likely hold for at least several more months, as a shaky vaccine rollout proceeds, and the rate of coronavirus infections ebbs and flows.

Ryan Masiello is co-founder and chief strategy officer at VTS, an online platform that tracks office leasing of non-Class C space in major business districts nationwide. In particular, VTS tracks new demand — companies looking for space before they lease. VTS’ info, then, is a good measure of leasing on the horizon. (It should be noted, too, that VTS is just the sort of proptech landlords and brokers increasingly say they’ll rely on.)

As far as Masiello and his company can see on that horizon, demand is fragile at best, and nowhere near robust. He took CO through some data in the first week in February, dealing specifically with demand for office space in prime New York City business areas.

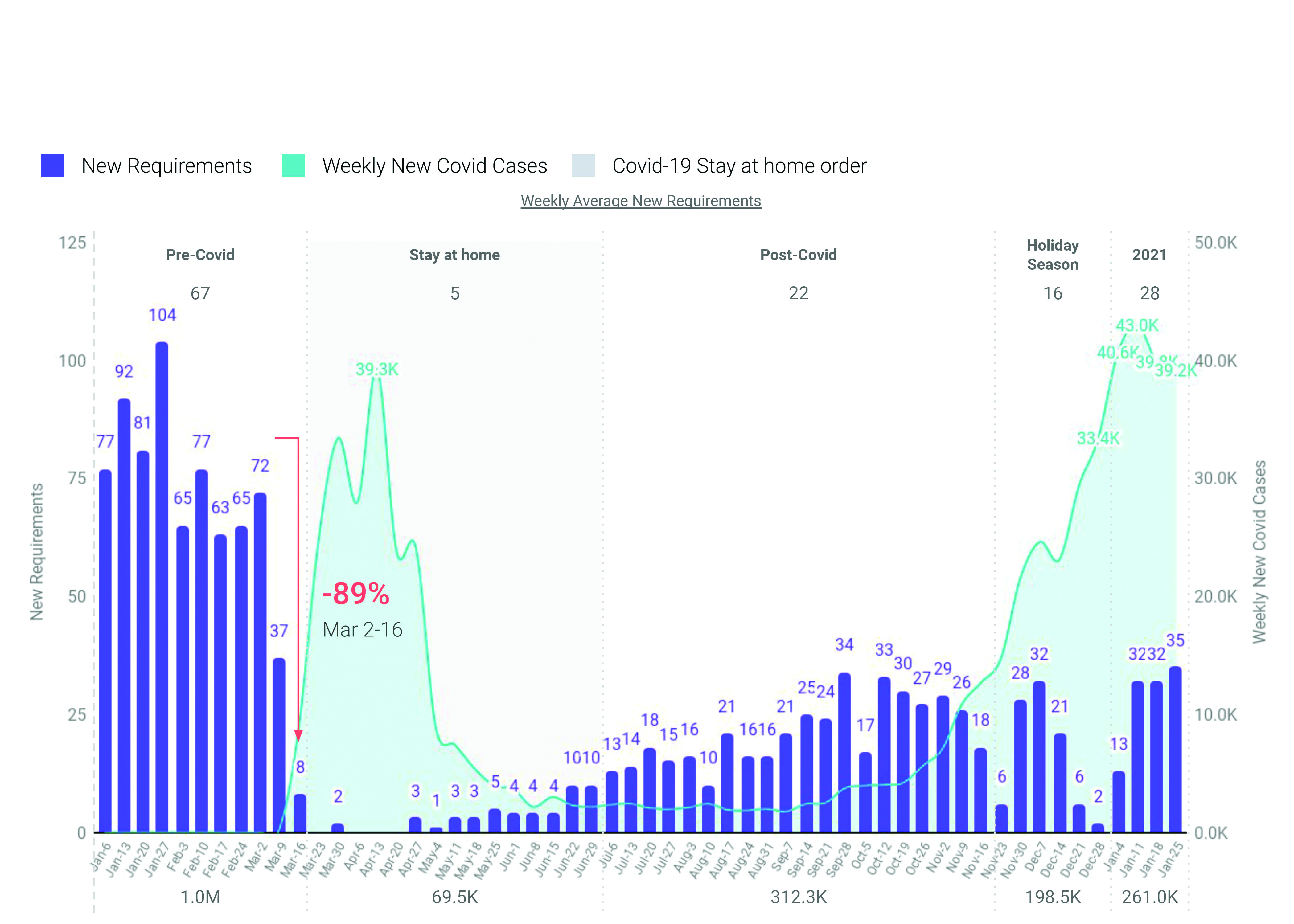

“You can see this kind of perfect inverse correlation between when COVID spikes and how tenants reacted,” Masiello said, while explaining a chart that showed hefty totals of companies looking to lease in New York City at the start of 2020, fresh off that busy 2019.

The number of companies looking declines sharply, though, after early March 2020 as COVID cases rise, and then picks up toward the fall, only to drop again as the year closes out and New York confronts another spike in virus cases (see chart).

The good news for landlords and their brokers is that the number of companies looking increased markedly this January, perhaps due to the vaccine rollout and a dip in the number of new COVID cases. There were 13 companies looking for the week ending Jan. 4, and 35 for the week ending Jan. 25, for instance.

“But the bad news is,” Masiello said, referring to that 35, “it’s 48 percent below the weekly pre-COVID average from a numbers-of-companies perspective, 69 percent below from a square-footage perspective.” Those 35 companies wanted a total of 342,000 square feet, to put it another way.

The increase in demand signals a reason for optimism, Masiello said, but it’s no reason to be particularly bullish on Manhattan office space.

“There will be this slow uptick this year, but I think we would be lucky if we saw two-thirds of the actual leasing activity for a normal year — that would be a home run,” Masiello said.

It might even be a home run in 2022, too. The Manhattan office vacancy rate is expected to rise through this year and next, to 12 percent, according to an analysis for CO from Victor Calanog, head of commercial real estate economics at Moody’s Analytics. His analysis placed the vacancy rate at 9.1 percent for 2020, up from 8.2 percent in 2019 — which, itself, was the lowest vacancy rate since 2008’s 8 percent.

On rents, the picture is a littler rosier, though not by much. Average asking rents are expected to decline through 2021 and 2022 — by as much as 6.1 percent this year, in fact — and then rebound slightly beginning in 2023, with an average of $69.71 a square foot.

Net effective rents are also expected to drop the next couple of years. That’s no surprise, really, given the drag on rents due to all of that sublease space. Effective rents are expected to drop 8.9 percent in 2021 and 1.7 percent in 2022, according to Moody’s Analytics, then rebound beginning in 2023.

Altogether, Calanog expects a tighter, more expensive Manhattan office market by 2024 and 2025. Vacancy rates will be between 11.5 and 12 percent, and both asking and effective rents should be on the rebound toward amounts seen before the pandemic. This will be good news for owners and investors who can hold on through the tumult.

Even then, though, rents are not expected to erase the pandemic-induced losses to get back to where they were in 2019. The average asking rent is slated to be $71.79 a square foot in 2025; in 2019, it was $75.26. The average effective rent was $62.49 that year, and should be $58.14 a foot in 2025.

These projections are based on decades of the Manhattan office market’s history. That, and the genesis of the current crisis, should give some comfort to owners and anyone else hoping to make pre-COVID money off the market.

For instance, the vacancy rates now and in the next couple of years have nothing on the early 1990s.

Due to a recession and several years of one new office development after another — some 9.793 million square feet of completed construction in 1986 alone, and another 8.8 million-plus in 1989 and 1990 — Manhattan’s office vacancy rates climbed above 17 percent, and didn’t drop below double-digit percentages until the latter half of the decade, according to Moody’s Analytics. At the same time, both asking and effective rents dropped steeply — more than 8 percent for both in 1991.

For that matter, as Calanog points out, effective office rents fell nearly 20 percent during the Great Recession. They’re expected to drop a total of 13 percent from 2020 through 2023.

Unlike the previous downturns, too, the current one is not economic, nor tied to too much supply and not enough demand. Net absorption of office space in Manhattan was 5.76 million square feet in 2019, despite 5.82 million square feet of completed construction.

Instead, it’s a downturn related to an unprecedented health crisis. Once the crisis passes, the recovery will by definition begin. Or, to put it another way, if COVID had never hit, the Manhattan office market would have chugged unexceptionally along, albeit with vacancy rising to about 10 percent by 2024 due to an influx of new space and rent growth slowing, though still staying positive, according to Calanog.

There are some caveats to this recovery out of COVID. One, as noted, it’s going to take a while — two years, maybe three, in terms of filling empty space and absorbing new space, and in terms of enough demand to drive rents higher.

In the meantime, two trends might scuttle the recovery, or at least push it even further past this year than 2023.

One is the rise and the relative success of work from home (WFH). Companies that had to shift to WFH at the start of the pandemic in March 2020 have signaled they might continue the arrangement in some form post-COVID.

Numerous surveys suggest the proportion of companies embracing a hybrid model and, therefore, consolidating and shedding their office space could be sizable.

Some 53 percent of 450 C-suite executives surveyed in August said they expected at least some increase in WFH during the next 12 to 24 months, according to a report from investment house KKR. A full 27 percent expected a significant increase in the number of their employees working remotely. The report showed that financial services, technology and professional services firms — all major occupiers of Manhattan office space — were the likeliest to be able to embrace WFH.

The sentiment, too, appears to have outlasted the news of vaccines. A PricewaterhouseCoopers survey of office workers and company executives in November and December found that fewer than 1 in 5 executives expect a return to the office on the scale of what was normal pre-COVID.

“The rest are grappling with how widely to extend remote work options,” PwC’s analysis of the survey said. Perhaps the sole good news in the survey for Manhattan landlords was that only 13 percent of execs thought the conventional office is over for good.

The other trend that could prolong the Manhattan office market’s recovery is the leasing demand from the technology industry — or the lack of it.

Analysts and brokers have long seen the technology, arts, media and information sector (or TAMI) as the likeliest successor to financial services, insurance and real estate (FIRE), as well as Big Law, in terms of animating the Manhattan office market.

The statistics belie that. From 2006 to 2008, just before the Great Recession, TAMI firms accounted for 3 percent of leasing deals in Manhattan, according to brokerage JLL. From March to December, during the pandemic, such firms were on the tenant side of 24 percent of all deals. What’s more, TAMI companies, such as Facebook and Tik Tok, accounted for well over half of all leases for newly constructed space — often the most expensive offices — during the first nine months of 2020, according to JLL.

Yet, it appears, at least for now, in 2021 that TAMI will not be carrying the Manhattan office market through its recovery. The sector fueled more than one-fifth of the demand for office space in Midtown pre-COVID, according to VTS. Post-COVID, that share fell to 6 percent. By comparison, demand from financial services firms was 35 percent and 37 percent, respectively.

“That’s the real red flag for New York at this point in time. Do I think tech will be here to stay long term? Absolutely,” said Masiello, whose own proptech firm has hired at least 70 people during COVID. “But, given the urgency to get back into the office, I think that is really going to be the biggest lever in slowing the ultimate driver of leasing activity.”

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)