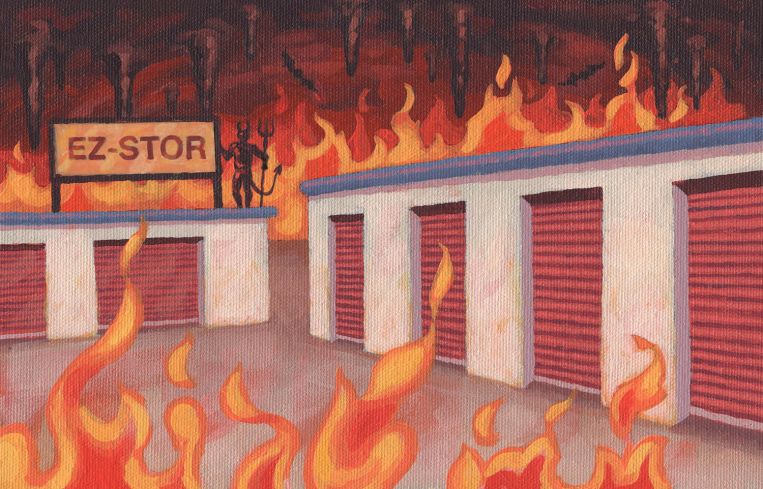

Self-Storage Is Winning the Pandemic

A commercial real estate sector that thrives on death, divorce and displacement looks ahead to a sunnier 2021

By Tom Acitelli November 13, 2020 2:26 pm

reprints

In October, self-storage operator CubeSmart closed on a $540 million purchase of eight storage facilities in New York City from developer Storage Deluxe. Malvern, Penn.-based CubeSmart bought the properties because of what it described as “a supply-starved market” that the coronavirus pandemic had done little to dampen, apparently.

The deal — which encompassed 780,425 rentable square feet, and which followed several other CubeSmart acquisitions in the five boroughs over the previous five years — underscored the resiliency of one of commercial real estate’s more steadily successful sectors.

“Certainly, compared to March or April, the industry has bounced back quite quickly,” said Chris Nebenzahl, a director at Yardi Matrix, a research company that tracks the self-storage industry. “We saw street rates falling in March and April, into May. They really stabilized in June and have since picked up even stronger than they have been.”

That these street rates, or rents, have tracked with the pandemic itself and the tightening and easing of related lockdowns since March is no accident.

The self-storage industry has long relied on what insiders describe as the four D’s: death, disaster, displacement and divorce. The pandemic has bolstered some of these conditions, and helped offset what had been a worrying trend for owners and operators in oversupply. But that trend is still worrisome, and the threat of another round of disruptive COVID-related lockdowns looms amid surges in virus cases nationwide.

As it stands now, though, the pandemic has highlighted self-storage’s resiliency compared with other commercial real estate asset classes. College students have had to move out of dorms, rental evictions have increased, and people trapped working remotely have cleared space for home offices, never mind the actual deaths from the virus. It didn’t hurt either that the for-sale housing market, too, picked up toward the end of the summer after a few straight months of declining sales, as moves often spawn self-storage leases.

At the same time, the industry continues to ride a decades-old wave of consumerism. Simply put, Americans bought a lot of stuff and needed a place to store it. Enter an increasingly professionalized industry that investors have come to view as a safe harbor amid more volatile sectors, such as retail and hospitality.

The modern self-storage industry grew out of the start of that consumerism wave in the 1960s. Cinderblock monoliths that often resembled parking garages popped up throughout the nation, mostly in the outskirts of urban areas. A wave of ownership consolidation led to a more professional self-storage industry. Larger players, such as real estate investment trusts and other institutional investors, began to dominate and reshape the industry. (Its largest players now are REITs, such as Public Storage, Extra Space Storage and CubeSmart.)

The leasing process and customer service became more formalized, and developments more strategic. Climate-controlled units proliferated in self-storage projects that came to resemble apartment complexes or office parks more than garages.

It all still hinged on the four D’s. And consistency from that served the industry well. Self-storage came out of the Great Recession in 2009 with strong street rate growth and steeply rising demand amid an economic boom that left more Americans with more things to stash. The number of U.S. self-storage facilities grew to more than 186,000 in 2020 from around 155,000 in 2011, according to an October report from research firm IBISWorld. Meanwhile, revenue increased 3 percent annually from 2015 to 2020.

This performance led to a surge in development and development proposals. The IBISWorld analysis projected a further 36,500-plus facilities nationwide by 2024, and Yardi Matrix calculated that the number of planned or underway projects came to account by the end of 2019 for nearly one in 10 self-storage facilities nationwide.

This surge led to nervousness among investors and operators surrounding street rates. It looked like supply might overtake demand long term. A Yardi Matrix analysis released in January showed street rates dropping in about three-quarters of the nation’s top self-storage markets, with more declines to come in the new year.

Then the pandemic hit in March, and the industry grappled with a whole other level of uncertainty. Various lockdowns forced owners to either curtail operations or close facilities completely. Stay-at-home advisories stymied visits from potential customers. Eviction moratoriums in various states and cities froze such actions against delinquent self-storage tenants. Street rates dipped further. Investment paused. One of commercial real estate’s safer havens seemed suddenly more dangerous.

“For a number of years, the institutional capital was slowly creeping into the storage industry,” Nebenzahl said. “March came around and COVID came around, and people said, ‘Whoa, let’s hit the brakes.’”

Yet the four D’s — or one or two of them, at least — appear to have carried self-storage through, from an ownership and investment point of view. The investment has picked up — in a particularly splashy way — and the most worrisome pre-COVID trend in the sector has started to roll back.

The number of newly created self-storage facilities is expected to fall about 10 percent for 2020, and by about 40 percent over the next five years, according to a Yardi Matrix report from September. Those that will get built will be delayed up to six months, the research tracker found. The report cited construction delays, as well as financing and permitting issues for the slowdown, but noted that it would not be an unwelcome trend in a market that had been fretting oversupply.

And that market seems to have responded favorably for owners, operators and investors.

Due to increased demand and economic re-openings in many places, September marked the first year-over-year growth in self-storage street rates nationally since 2017, Yardi Matrix said. The largest self-storage REITs saw average rates increase about 12 percent in October, too, according to Green Street. That followed an 8 percent rise in September. (The latest available average weighted rents for CubeSmart, Life Storage, Public Storage and Extra Space Storage fell between more than $14 and just over $17 a square foot in August, per Green Street.)

At the same time, the last few months have seen some of the most high-profile investments in self-storage since institutional investors began creeping in 10 to 15 years ago. In mid-October, StorageMart, which bills itself as the world’s largest, privately held self-storage firm, announced that it was taking on minority investors in a deal that valued the firm at $2.7 billion total. These investors included Cascade Investment, a private investment vehicle that billionaire philanthropist and software tycoon Bill Gates exclusively controls.

Less than two weeks later, Blackstone’s real estate investment trust announced it was buying Simply Self Storage, one of the country’s five largest self-storage firms, from a Brookfield Asset Management fund in a deal valued at $1.2 billion.

There have been smaller deals, too, including CubeSmart’s play for Storage Deluxe sites in New York City. These trades are helping self-storage’s reputation in the short term during the pandemic, as well as in its long evolution beyond being seen as an alternative investment.

“The more institutional capital sources like these pursue storage, other debt and equity sources will start to look at storage as more mainstream,” said Joe Iacono, CEO and managing partner of Crescit Capital Strategies, an asset manager based in Manhattan.

Such investment, coupled with the upticks in leasing and rent, has it seeming like the self-storage industry skipped the pandemic. The wider industry is back to worrying about fundamentals like supply and demand.

“Where there’s pressure on fundamentals, it’s far more driven at this point by the supply cycle than it is by anything related to the bigger economic picture or pandemic,” said Ryan Clark, investment sales director at Tampa-based SkyView Advisors, which specializes in self-storage.

The resiliency has made self-storage a port in the storm again, much as it did post-Great Recession. Investor interest is coming from individuals and firms that usually buy into typically better-performing and more scalable asset classes. That’s because some of those sectors, especially retail and hotels, are faring poorly during the pandemic. Delinquencies and bankruptcies are high and returns uneven.

“We’re seeing a lot of crossover money,” Clark said, “money coming in from hotels, from multifamily, from retail investors who see the consistent returns that self-storage has been able to generate.”

Revenue and net operating income for the largest self-storage REITs are expected to end 2020 flat, but start ticking upward in 2021 and 2022, according to Green Street.

The commercial real estate intelligence firm also found during the pandemic that self-storage was a better financial investment, in terms of returns, than some of the usually more vaunted commercial real estate sectors.

At a 5.9 percent risk-adjusted rate of return in August, the latest month for available figures, self-storage performed better than office, industrial, and even life sciences, which has garnered particular attention given its growth due in part to the race for COVID therapeutics and vaccines. It also outpaced struggling hotels, but fell well-behind returns on multifamily, single-family rentals and health care, among other sectors.

Still, self-storage faces challenges, both in the long- and the short-term. Whatever dip in future supply, there’s still enough oversupply to risk rate declines again. And another round of COVID-related lockdowns this winter could destabilize things further. In the end, 2020 might end up a wash.

As a Yardi Matrix assessment for the fall put it: “The slog in self-storage continues for the next 18 to 24 months, with some emerging upside.”