A Moratorium on Moratoriums: California’s SB 330 Clears Obstacles to Housing

Against NIMBY wishes, the new bill will remove added costs and barriers to new development, and suspend new local restrictions for the next five years.

By Greg Cornfield September 13, 2019 7:03 pm

reprints

A new state housing bill that will suspend added development restrictions by local governments, such as housing moratoriums and added fees, is set to become law.

Senate Bill 330, called “The Housing Crisis Act,” is made to address the housing shortage in California and spur more multifamily development by cutting down on the added costs and barriers involved with obtaining permits for housing. It aims to eliminate the top reasons cited by residential developers for the current homebuilding slowdown: Cities and counties adding new limits and fees on projects, and the lengthy delays that come after submitting applications for much-needed housing.

The bill is on its way to Governor Gavin Newsom, who has said he supports it. He has until October 13 to sign it into law.

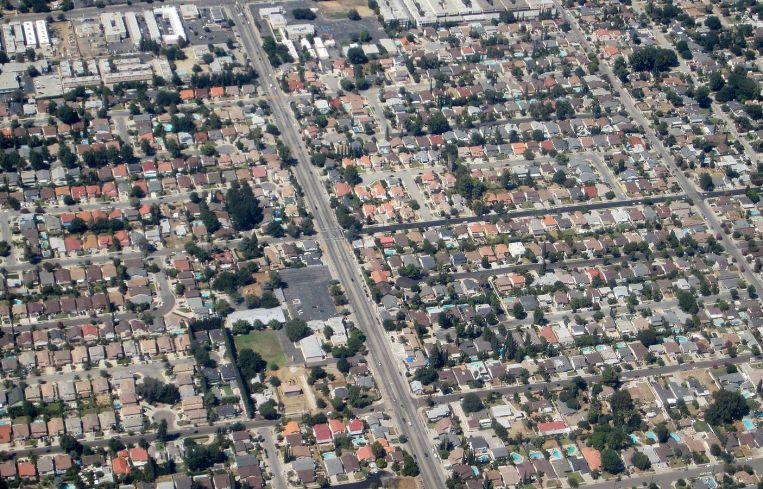

Newsom also set an ambitious goal and called for the creation of 500,000 new housing units per year, and for 3.5 million units over the next seven years. To achieve that, he’ll need bills like SB 330 to get there, considering state housing department reported that less than 80,000 homes have been built annually over the past decade. The state ranks 49th in the nation in the number of housing units per capita, and this scarcity has led to a median home price of more than $610,000. And in May, the California Housing Partnership estimated that Los Angeles County alone needs more than 500,000 homes to meet its current demand.

“Our failure to build enough housing has led to the highest rents and home ownership costs in the nation,” said State Senator Nancy Skinner, the author of the bill, in a statement.

She explained that the bill is based on the idea that a significant amount of housing projects that could help ease the shortage have already been planned. According to the UCLA Lewis Center for Regional Policy Studies, California cities and counties have approved zoning for 2.8 million new housing units. According to the L.A. Conservancy, a nonprofit organization that advocates for historic preservation, about 820,000 parcels are available in the city for new development, increased density, and much-needed housing.

“But that housing is not getting built,” Skinner’s statement continued. “In fact, the number of residential building permits in the first six months of this year plummeted nearly 20 percent compared with the same period in 2018.”

In effect, SB 330 will enact a moratorium on moratoriums, and prohibit housing limits and density reductions. The law opens the door to development by suspending new local restrictions and regulations for the next five years. It will prohibit a county or city from enforcing a moratorium on housing development, making new restrictions, or down-zoning, and it overrides local planning in favor of higher density projects in areas currently limited to single-family development.

Marne Sussman, a partner at Holland & Knight, told the Commercial Observer that she doesn’t expect SB 330 to lead to rapid housing production, and it’s not the ground-breaking legislation the state needs to open the floodgates to housing development, like SB 50 could have been by up-zoning massive amounts of properties throughout the state. But she said it’s an incremental step in getting there, and will eliminate uncertainty and some of the risks involved in the long entitlement process for developers.

“It will help hold cities and counties more accountable for their planning,” she said, and require them to stick to the housing in their general plans.

If a developer proposes a project that adheres to a city’s general plan, SB 330 will help ensure the project can become a reality, she said. With SB 330, cities can still set their own standard, but once it’s set, they can’t try to change them.

“You shouldn’t be able to turn around and deny those projects,” she said.

Construction has been stalling as builders face increasing costs from new requirements like those involved with Measure JJJ, which requires labor unions for developers who need to amend the zoning of a property, which costs about 20 percent more. But Sussman said it’s not always an issue for developers about high fees are. Rather, it’s when the fees are changed along the way, it makes the process more difficult for builders.

“It will affect just about all jurisdictions, especially if the ones that aren’t as pro-growth,” she said, pointing to areas in the Los Angeles region that fight development or otherwise don’t want it, and “push back against requirements to find properties for housing development.”

Municipalities in Los Angeles County and throughout the state have a track record of restricting development. For example, the city of Redondo Beach imposed a moratorium on mixed-use residential projects for nearly a year in hopes of easing traffic and preserving the city. And Huntington Beach in Orange County received a lawsuit from Newsom in his first month in office for not complying with state requirements to dedicate land for low-income housing. That city lowered its housing stock in 2015 after officials enacted a stricter cap on the number of new units allowed.

SB 330 also aims to speed up the entitlement process for projects that would add new housing by establishing a 12-month period for processing all housing permits. It also limits the number of public hearings for new housing development to three total.

It can take years for a developer to break ground after filing for a project. The process has expanded to a point where a market has grown in Los Angeles for entitled properties that are shovel ready, as firms chose to avoid the burdensome approval process.

Finally, the bill bans the demolition of affordable and rent-controlled units unless developers replace all of them and pay to re-house tenants and offer them first right of return at the same rent.

SB 330 was backed by the California Building Industry Association and the California Association of Realtors.

In a statement, C.A.R. president Jared Martin said SB 330 will “create certainty in the development application and permitting process for developers building new housing units, while expressly prohibiting local governments from changing the rules surrounding development fees in the middle of the game.”

Update: This story has been corrected since publication to reflect the correct number of parcels that are available in Los Angeles for new development.