While Occupancy Skyrockets, NYC Hotel Players See Cause for Concern

Room rates continue to fall while lending constraints, regulatory environment could hinder future pipeline

By Rey Mashayekhi February 8, 2018 10:00 am

reprints

Over the past several years, the unofficial motto of the New York City hotel market has been “If you build it, they will come.” Tens of thousands of new hotel rooms have cropped up across the city this decade, and there are tens of thousands more in the pipeline due to arrive in the coming years—but despite all that new supply, the rooms keep getting absorbed.

That’s undoubtedly good news for the hotel developers and operators who built those new rooms and plan on bringing more to the market in the near future. But a closer look at the statistics and conversations with hotel market participants reveal a more mixed view of the city’s hotel landscape—one that finds it attempting to strike a balance between the number of rooms sold and the prices being paid for those rooms, and bracing for a variety of headwinds that could make it hard to sustain future development.

The clear, undoubtedly positive story is that while the U.S. hotel industry has struggled recently—with declining tourism figures among the factors that have made it difficult to absorb the roughly 2 percent supply growth experienced nationally last year—New York City has shown little problem handling the 4 percent growth in its supply that it saw in 2017. As Jan Freitag, the senior vice president of lodging insights for data and analytics firm STR, put it, the city’s hotel market is experiencing a dynamic that “doesn’t make sense in any other market but does make sense in New York City.”

The average occupancy of New York hotels in 2017 stood at 86.7 percent, up 1.1 percent from the previous year—with the city now home to more than 119,000 hotel rooms across the five boroughs, according to STR. That 86.7 percent occupancy rate means that nearly nine out of 10 hotel rooms available in the city were sold out through the course of last year—a “stunning” figure given the added supply, Freitag said.

“What demonstrates the strength of the New York market is that all of those hotel rooms are being absorbed in the year that they open,” said Mark VanStekelenburg, a managing director in the hotels division at CBRE. “From an occupancy standpoint, the market is at or near its peak occupancy and is continuing to be, even while we’re experiencing 4 to 6 percent [annual] supply growth. We’ve never really seen something like that in the U.S.”

That should give confidence to the city’s hotel developers, given that room supply will only continue to grow in the next few years; STR tracks more than 22,000 new rooms presently in the city’s development pipeline, including nearly 12,000 that are presently under construction.

But while the city has shown an ability to absorb that kind of supply influx, the underlying economics of doing so—such as the daily rates those rooms are able to command and the revenues flowing into the pockets of hoteliers—are somewhat murkier.

Though hotel occupancy in New York has been on an upward trajectory, average daily rates have not; those slipped 1.4 percent to $255.54 in 2017, according to STR. Room rates in the city have continued to slide since peaking at more than $271 per night in 2014, as has the metric of revenue per available room (RevPAR), which has fallen 4.6 percent to $221.60 in that time.

Market observers attribute this inability to translate high occupancy rates to improved room rates and revenues to a number of factors. Some noted that most of the city’s new hotel rooms fall under the booming limited- or select-service category, where rates are on the lower end of the spectrum (such rooms comprise more than 6,000 of the nearly 12,000 rooms currently under construction in the city, per STR). Others cited the influence of Airbnb, which has forced hoteliers to re-evaluate the prices they ask of consumers who can now choose a cheaper, often more spacious lodging alternative.

Still, despite softening rates and the promise of even more supply to come, it’s not hard to find real estate players willing to bet on the hotel market’s continued viability.

“You can see from our commitment to the city hotel market that we’re still very bullish in our long-term view of hospitality investments,” Mitchell Hochberg, the president of the Lightstone Group, said.

Hochberg pointed to his development firm’s hotel projects around the city, such as its Moxy brand hotels in Times Square, NoMad and the East Village, as examples of Lightstone’s continued faith in the hotel sector. “New York is one of the strongest economies in the country, and it’s a global center for finance and media,” he said. “Although there’s been a supply increase in the last couple of years, the data indicates that demand has kept up with supply.”

But other hotel market players are far less convinced. Richard Born, the co-founder of BD Hotels and the hotelier behind boutique Manhattan brands such as the Mercer Hotel, the Greenwich Hotel, the Ludlow Hotel and the Jane Hotel, espoused his view that, “with some exceptions, by and large the hotel market in New York is terrible.”

He cited a combination of factors including the “erosion” of daily rates (which he attributed to the influx in room supply as well as Airbnb’s vast “shadow inventory”), higher property taxes and operating costs, and the increased influence of third-party booking websites like Expedia and Travelocity (which have brought more transparency and reduced hotels’ “pricing power” while also charging booking commissions that are an additional “line item” for operators).

“Any hotel operator operating today is making a fraction of their net operating income compared to what they were making 10 years ago,” Born said. He added that the operators best positioned to succeed in such a challenging market are the ones capable of differentiating themselves from the more malleable product of their competitors. “There’s a fungibility to the hotel market that makes pricing very difficult because everyone is looking at everyone else’s rates. But the exceptions are the hotels that are not fungible—the ones that are unique, designed and have something different to offer their customers.”

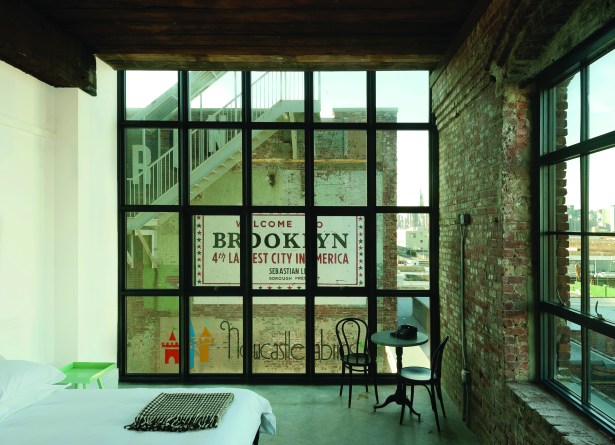

In addition to its higher-end boutique brands like the Mercer, Bowery, Ludlow and Maritime hotels—where rates are on the higher end of the pricing spectrum—BD Hotels has sought to differentiate itself from the landscape with projects like its Pod hotels, which have parlayed the micro-apartment trend into a concept the hotelier terms the “micro-hotel.” With four locations in New York and one in Washington, D.C., the Pod hotels offer nightly rooms of around 100 square feet but also come equipped with food-and-beverage concepts and boutique-minded aesthetics (such as the mural from Brooklyn artist JM Rizzi that adorns the elevator shaft at the recently opened Pod Times Square).

Born pointed to the Pod BK—the brand’s Williamsburg, Brooklyn location—as offering something specifically different from the new luxury hotels that have cropped up in that neighborhood in recent years, such as the Wythe Hotel and the William Vale. “We have a hotel that we don’t think is fungible, in a marketplace where all the hotels are four-star boutiques looking for high rates,” he said.

Hochberg cited a similar rationale behind Lightstone’s Moxy brand; the developer teamed up with Marriott International with the goal of “delivering an affordable product with a lifestyle component to it”—one that offers the sensibilities of a boutique product at a lower price point with smaller rooms and limited-service offerings.

“The industry has introduced many more products and choices for the consumer of the past few years,” Hochberg said. “There’s a whole variety of new genres and brands that are focusing more on the consumer and trying to understand what today’s consumer is looking for.”

Hoteliers may also receive a boost from the fact that, beyond this decade, the city’s hotel development pipeline is slated to slow down significantly, making it easier for the incoming supply to be absorbed and potentially driving up room rates again.

Multiple market observers and participants noted that the supply influx the city is now seeing is the result of plans initiated a few years ago, adding that a variety of factors—from risk-averse lenders shying away from financing new projects to regulatory pressures being placed on the hotel sector by the de Blasio administration—could slow future development significantly.

“When we go out to find financing, there are less people able to provide debt than there were before,” said Eastern Consolidated’s Adam Hakim, a managing director in the brokerage’s capital advisory division. “Lenders control supply and demand; when they give hotel developers money, people build hotels, and when they don’t, they can’t.”

Hakim’s colleague James Murad, a director at Eastern, described the hotel market as “one of the thinnest construction financing markets you can go out for” to procure funds, with lenders mindful about the sheer volume of new supply and how that may affect borrowers’ abilities to refinance in the future.

“That said,” Murad added, “for quality sponsors and the right product, there’s appetite.”

Jared Kelso, a senior managing director in Cushman & Wakefield’s global hospitality group, echoed that sentiment. “The last 24 months have been very challenging to find construction financing [for hotels],” he said, attributing the slowdown to lenders being in a “checklist underwriting” mind frame in considering hotel market fundamentals.

But Kelso added that financing is still available to “sponsors with a long and proven track record” with debt funds and alternative lenders also stepping in to fill the void left by the more risk-averse banks. He also noted that the tightening of the financing market is “frustrating for developers but not a bad thing at large” given the impact it will have on restricting supply. “After 2018, the supply pipeline thins dramatically, and that will ultimately be a good thing for the [hotel market] at large.”

And then there are regulatory obstacles that market observers say will impede hotel development in the future. That includes the de Blasio administration’s proposal to limit projects in industrially zoned M1 manufacturing districts by requiring developers to obtain a special permit, as well as the extension of Local Law 50, which prohibits large hotels (150 keys or more) from converting more than a fifth of their rooms to residential units or other non-hotel uses without city approval.

Both measures are perceived by many observers as meant to preserve the interests of the influential hotel workers’ unions and potentially damage the city’s future hotel supply. In the case of the zoning proposal, it will make it harder for developers to find parcels to build on and likely subject those projects receiving a special permit to higher-cost union labor requirements; in the case of Local Law 50, its preservation of existing hotel rooms would dampen the need for new supply in the interest of preserving existing hotel jobs.

According to Hakim, some of the developers behind the current supply pipeline—such as prolific hotel builder Sam Chang of McSam Hotel Group, a client of Eastern’s—are operating on the “thesis that hotel values are going to go up significantly in the next few years. The inventory is going to stabilize, and once it stabilizes, the theory is that you won’t be able to build new ones.” (Chang did not return a request for comment.)

“Twenty-four months from today, in 2020, I think your pipeline of hotels is going to drop to pretty close to zero,” Hakim added. “From there, you’ll see an increase in [room] prices.” But he was also critical of the influence that the current regulatory environment has had on exacerbating this dynamic. “I believe markets should correct themselves properly; you have a lack of [financing], and that’s a correction you’re seeing. But public policy and zoning laws being arbitrarily changed—that’s not how it should work.”

The de Blasio administration, for its part, does not think the proposed zoning regulations will negatively impact the flow of new hotel projects in the city. “We don’t believe the proposed rules will hinder hotel development across the city, which remains strong,” a mayoral spokeswoman said in a statement. “But we do aim to prioritize manufacturing businesses in the zones specifically designated for manufacturing. While hotels have a lot of options for where they can open and operate, these industrial firms don’t.”

The impact of all these various influences could start making themselves felt sooner rather than later, sources said. C&W’s Kelso said that the brokerage believes New York City room rates could start ticking upward as soon as the fourth quarter of this year, while Hochberg said Lightstone projects RevPAR “to be flat to slightly increased in 2018.”

That would be good news for hotel operators in the city—and a testament to its voracious appetite for hotels. Despite all the new supply, the city’s churning economy and robust tourism sector seems to always make room for even more places where people can stay.

“It’s a cultural mecca for the world,” Born said. “Every 14-year-old lives on a handheld device, looking at all this and dreaming of coming to New York, whether you’re in Oklahoma or Bangladesh, to live, work, study and visit here. It’s always going to be a dynamic place for tourism—the issues are going to be the costs of operating and the supply. But we do live in the greatest tourism market in the U.S. and in the world.”