Despite a $17B Valuation and Expanding Business Model, How Long Can WeWork Work?

By Tom Acitelli June 20, 2017 6:00 pm

reprints

In the first quarter of 2017, technology firm Edulence took space in 79 Madison Avenue, a NoMad building where coworking giant WeWork operates 10 of the 17 floors.

For Edulence, which specializes in subscription platforms for educators and other experts, the move closed a real estate circle. The company had launched in 2002 in tech incubator space in New York not unlike the sort WeWork leases, creates and operates.

Then, as it grew, the company went the more traditional route: It leased 5,000 square feet of conventional office space in the Union Square/Flatiron District area, long term.

Soon, though, more employees were working remotely, and Edulence reassessed its real estate needs.

“They had decided that their model had changed, and they didn’t want that amount of space,” said Andy Udis, a partner at ABS Partners Real Estate and Edulence’s broker.

So, in an agreement typical of deals with WeWork, Edulence rented parts of 79 Madison on a month-to-month basis for costs based on the number of employees or the number of desks it might need. (Some employees, after all, don’t use desks, as you see in the typical tech incubator.) A desk at 79 Madison costs $550 a month per person, and private offices start at $800 a month.

It wasn’t just the flexibility that the short-term agreement created that the company found appealing, Udis said. It was that WeWork handles much of the office-related responsibilities that often fall to firms in more traditional setups: cleaning services, copious amounts of coffee, high-speed internet, even social and networking events.

So, while it might cost renters more to occupy WeWork space rather than more familiar office floorage, the allure for entities that don’t want 10 or 15 years of set space is powerful, particularly in industries where turnover can be high and layoffs routine.

The model has served WeWork well: The Soho-based company now operates 33 locations in Manhattan, four in Brooklyn and one in Queens—never mind 149 worldwide with a further 40 planned as of mid-June. It does not break out the amount of space it actually controls and leases out to individuals and businesses, according to a WeWork spokesman. But industry figures familiar with WeWork said it’s probably around 3 million in New York City. (WeWork otherwise declined to comment for this article.) That much square footage makes them no longer a peripheral player in New York’s office market but a major one.

The company also surpassed Google parent Alphabet in 2016 as the nation’s largest leaser of new office space, according to CoStar Group. Also, its valuation earlier this year hit $17 billion, and it signed a major deal with IBM, one of the world’s largest and most durable technology companies. And just last week, Adam Neumann, WeWork’s co-founder and chief executive officer, told attendees at a Wall Street luncheon that the company is currently generating revenue at a rate of $1 billion annually, and is planning to launch an initial public offering in the future (Neumann did not specify a time frame for the IPO).

Such turns have had people comparing WeWork to the likes of Uber in its capacity to disrupt its industry. And similar kinds of criticism leveled at Uber could probably be tweaked to apply to WeWork—another company with seemingly gargantuan potential not yet fully realized. (Uber lost $2.8 billion last year, according to New York magazine. WeWork is hardly losing money, but it is a multibillion-dollar real estate company that doesn’t own any real estate, much like Uber doesn’t own any cars.)

Its success—and potential for more—has divided real estate professionals in New York: Those who are willing to accept WeWork’s vision of its place in the real estate firmament and those who are not willing.

Sam Zell, the chairman of Equity Group Investments, which includes major office properties, put it like this during a May appearance on CNBC: “We have yet to find out what happens to WeWork when the office market softens, which is probably not too long from now.”

However blunt that comment is, it is nothing compared with earlier criticism. In June 2015, Empire State Realty Trust’s Anthony Malkin dismissed WeWork as something that would forever remain small fry.

“When these companies grow up,” Malkin, the trust’s chairman and chief executive, said of WeWork’s clients, according to The Real Deal, “they’ll want a real building and a real landlord.”

Such strong talk is no longer as much in vogue, according to several interviews with those in the industry. That is because for now WeWork seems to be working quite well in New York.

But suppose WeWork brewed fantastic coffee, and nobody showed up to drink it?

The story of red-hot WeWork begins, ironically enough, amid a cooling office market.

It was just after the 2007-2008 financial crisis, which drove the Manhattan office vacancy rate to more than 13 percent, according to brokerage reports (and which would not come down to pre-recession levels until 2016). That was the highest level, in fact, since the late 1990s and reflected widespread layoffs and the quick liquidation of unnecessary space.

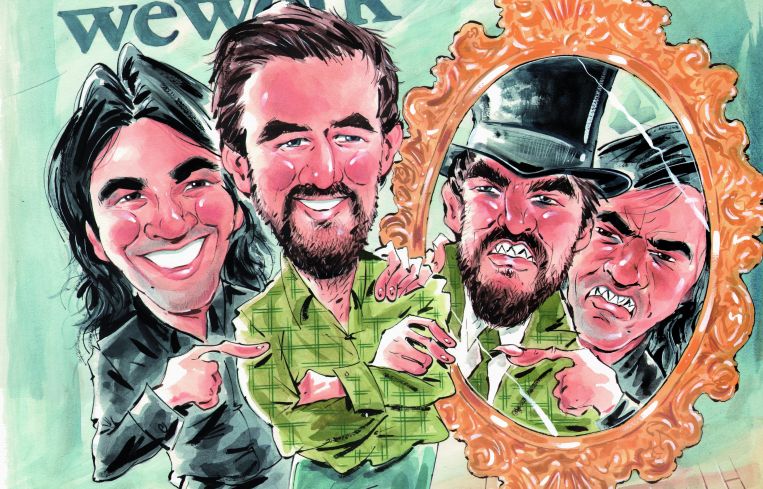

Adam Neumann and Miguel McKelvey saw an opportunity in the tumult. The pair had started and sold a Brooklyn-based company called GreenDesk, which rented out environmentally friendly coworking space, and decided to do much the same thing on a larger scale with more services thrown in.

What the pair called WeWork would include perks such as social networks, in-house cafés, even health insurance, never mind standard office fare such as desks and wireless. (They dropped the green focus.)

WeWork launched in 2010 in Soho and, within a few years, had drawn investors such as Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan Chase. By 2014, it was the fastest-growing leaser of office space in New York City, according to Forbes magazine.

It seemed to have had perfect timing, catching the sharing-economy wave that popularized other startups such as Uber, Airbnb and TaskRabbit.

Then came 2016, when WeWork overtook Alphabet as the nation’s largest new-office leaser and a round of venture-capital fundraising pegged the company’s value at around $17 billion.

A year later, Japan’s SoftBank used that same valuation in investing $300 million in WeWork. The Wall Street Journal reported that sum is probably mere prelude to a $3 billion investment total.

While it’s no Uber, with its approximately $70 billion valuation, WeWork, only seven years old now, could easily soon overtake Airbnb, the apartment-renting hotel disruptor. A March fundraising round put Airbnb’s worth at about $31 billion.

WeWork doesn’t face the same regulatory headwinds in office leasing that Airbnb does in renting apartments or Uber in taxi hailing—in those cases, states and cities, including New York, have tried to curtail their reaches, often in defense of the traditional industries they’re upending. No such effort has been made to stymie WeWork.

Its only limit seems to be the office market itself, and that has led to a division in the New York real estate industry over WeWork, particularly that $17 billion—and counting—valuation.

The difference in opinion boils down to how industry insiders and analysts view the durability of its business model.

On the one hand, according to an executive at a major New York landlord, WeWork has a “very good reputation” in terms of operating its space. The amenities and the community fostering come in for particular praise. Moreover, as another executive pointed out, a leasing deal with WeWork can reduce risk to the landlord because the coworking company covers much of the space buildout that would otherwise fall with the owner.

Some see a harbinger of the future office environment in the WeWork setup, according to this executive—a sign that just so happens to be helping along a scorching-hot Manhattan office market.

Average asking rents hit an all-time high of $73.92 a square foot for the overall Manhattan market in the first quarter of 2017, according to a Colliers International report, whereas a hot desk at WeWork starts at $220 per month.

A particularly tight market—the vacancy rate was 6.5 percent in the first quarter—is sustaining such rents as private companies lease what’s available and the only real substantive new office spaces coming online this year are “modest…boutique properties in Midtown South,” according to Colliers.

Plus, it doesn’t hurt its reputation in the industry that, for now at least, traditional direct landlords do not view WeWork as much of a threat. If anything, these landlords have taken a kind of benign view of WeWork as part of the larger coworking phenomenon, one that will go up and down with the market.

Grant Greenspan is a principal at the Kaufman Organization, a commercial landlord with more than 6 million square feet. He sees WeWork, too, as a kind of incubator for direct landlords such as his firm. Tenants might start out in a coworking space, such as one that WeWork runs, and then graduate to larger digs in spaces that more traditional landlords operate.

“I would say 30 percent, 40 percent of my leasing traffic and leasing business is still coming from that coworking sector,” Greenspan said.

On the other side of the opinion divide are those like Zell, who see WeWork in much more malignant terms. Its success contains its fatal flaw, one that might one day spill a lot of empty office space onto the market.

What if the economy currently sustaining this hot Manhattan office market suddenly turns? Things were as rosy in 2007 and 2008, right before the last downturn, as they are today, a real estate executive noted.

Then came the recession and a once-in-a-generation dumping of office space onto an unprepared market.

WeWork might be part of that spill. As one analyst put it to CO, a company using WeWork space would surely pull employees from that space at the first opportunity to save money. The employees would be told to work from home or at the corporate office, the analyst said. As for individual freelancers renting WeWork space, the flow of their paying assignments would presumably ebb in an economic contraction. They, too, would not need to rent a remote desk.

Then what?

In April, IBM inked a deal for all of WeWork’s 70,000 square feet in eight floors at 88 University Place just south of Union Square.

The deal represented the first time a single corporation had taken the entirety of one of WeWork’s New York City locations—IBM plans to relocate around 600 employees to 88 University from 51 Astor Place nearby (and probably elsewhere)—and points to a third possible way for the company to dig into the larger economy or the local office market.

Instead of a razor’s edge between obsolescence due to a downturn and success due to legions of freelancers and smaller companies, WeWork might lean instead on larger, marquee names. These names can weather a downturn better, the logic goes, and not leave WeWork holding large blocks of space.

The approach, which the IBM deal seemed to signal, did not go unnoticed in the industry.

“Here’s IBM, a large corporate tenant with I’m sure very defined, specific real estate workspace conditions, going into a WeWork,” said Udis, who was not involved in the deal.

Terms of that April deal are not known beyond the location, IBM’s estimated headcount for the space and that it was a membership deal wherein the company bought into WeWork’s space as well as its services. The ability to farm out office-management services to WeWork would appeal as much to bigger players, such as IBM, as it does to smaller companies, Udis said.

Whether deals with better-established companies, such as IBM, buoy WeWork in the bad times—and whether the company even has such deals pending—remains to be seen. The economy is still doing well, and the city’s office market is still one of the tightest in the world.

Should things turn, though, the $17 billion disruptor may turn out to be not necessarily fatally flawed but something perhaps much worse for a high-flying startup: utterly normal.

“I don’t know how much pent-up demand there is,” Francis Greenburger, the chairman and chief executive officer of Time Equities, which controls 23 million square feet worldwide, said of WeWork. “It may already be well-satisfied. [WeWork] will follow the normal ups and downs of the economy, just like all real estate usage does.”