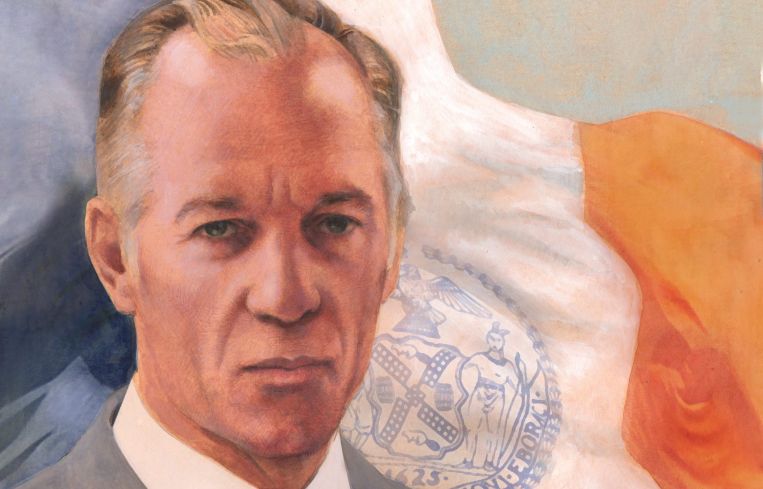

Paul Massey Takes on de Blasio, Long Odds With Mayoral Bid

By Rey Mashayekhi April 19, 2017 8:30 am

reprints

On a mild evening in early March, in an ornate yellow-dinned conference room located on a golf course in Dyker Heights, Brooklyn, Paul Massey took the stage at the Brooklyn GOP Mayoral Candidates Forum. Standing behind a podium, before dozens of local Republicans, Massey—who built one of New York City’s most successful commercial property sales brokerages over the course of a 30-plus-year career in real estate—made his pitch as to why he is the man to unseat Mayor Bill de Blasio in the mayoral election this fall.

“My wife had a lot of trepidation about this,” Massey told the room of his unlikely run for the city’s highest elected office. His wife, Gretchen, was a Hillary Clinton supporter, and Massey relayed an anecdote about how his youngest daughter had burst into the family’s living room after rumors began circulating last winter that Clinton was considering her own run for City Hall. “You’re dead!” Massey’s daughter had said.

The 57-year-old then launched into his stump. Massey, as has been frequently noted by the New York political press, is not a naturally gifted public speaker; charming and personable in one-on-one conversation, his delivery before a room of people can come across as clunky, cautious and overly considered. But that did not hinder the withering nature of his attacks on de Blasio.

“I think he has let us down,” Massey said of the mayor, describing a “leadership vacuum” at the top of the city government. He pegged de Blasio as “corrupt” and criticized him for rhetoric that was dividing the city into “rich against poor, black against white.” Massey didn’t stop there. “The laziness is something I can’t countenance,” he said, attacking the mayor’s work ethic and alleging a habit of “strolling into the office at noon.”

Massey, by contrast, “was at my desk before 7 a.m., every day for 30 years” (a habit frequently cited by colleagues and friends). As he has repeatedly mentioned on the campaign trail, he arrived in New York City in the 1980s, fresh out of Colgate University—where he was briefly kicked out for “not studying as hard as I should have,” as he told Commercial Observer last year—with $150 in his pocket. He worked as a bartender before landing a job at Coldwell Banker (now CBRE), where he met another young real estate broker named Robert Knakal. The two eventually decided to strike out together in 1988, forming their own commercial brokerage, Massey Knakal Realty Services.

Over the next two decades, the firm would grow to dominate the mid-tier investment sales market in New York, initially focusing on Manhattan and eventually extending its business to the outer boroughs. In 2015, Massey and Knakal sold their company to commercial real estate giant Cushman & Wakefield for $100 million, with both men joining the C&W empire as part of the deal.

“We started the business with nothing,” Massey, speaking in his native Bostonian lilt, told the room. “It wasn’t easy along the way…We scratched and clawed.” His experiences, Massey claimed, meant that he could relate to the everyday struggles of ordinary New Yorkers. What’s more, he would bring the same, client-focused approach that had served him so well as a real estate executive to the job for which he was now applying. “You’re going to be our clients,” he said to the assembled citizenry.

A Massey administration, he said, would be beholden to no special interests; the campaign had taken no donations from political-action committees or lobbies, Massey claimed—despite having a list of donors featuring some of the most influential real estate brokers, developers and landlords in the city. The mayor, by contrast, found himself the subject of multiple investigations by the likes of the U.S. Attorney for Southern District of New York and the Manhattan District Attorney, including inquiries into his campaign fundraising practices.

All the while, the gathered crowd listened intently as Massey worked his way through a litany of campaign issues. From quality of life to education, from public infrastructure to homelessness, he described the current state of the city as “unacceptable” and offered himself as the solution to New York City’s malaise—“I’m the answer,” he said. Massey then took several questions from the room about issues including stop and frisk (“I think we should let the police do their job…I don’t believe in racial profiling”), women’s reproductive rights (“I am pro-choice”) and immigration (New York, he said, is a “city of immigrants”).

He then ceded the stage to his only other declared opponent in the GOP mayoral primary at the time, Rev. Michel Faulkner. An All-American college football player who had a brief stint in the NFL in the early 1980s, Faulkner is a physically imposing figure with the charisma to match. Having moved to New York City around the same time that Massey and Knakal were starting up their brokerage, Faulkner spoke of how “God called me to serve” at a Times Square soup kitchen and how the experience had propelled him into a career as a pastor.

Faulkner—who, unlike Massey, has been vocal in his support for President Donald Trump—slammed the government for “taxing the middle class out of the city.” He told his fellow Republicans that while they need not model themselves after Democrats to win City Hall, they would “never win another election” in New York if they couldn’t reach African-American and Hispanic communities. The path to victory, Faulkner said, would be through a platform focused on “crime, education, jobs and ethics” and the advocacy of “market-driven principles.”

The room at Dyker Beach Golf Course, pensive and reserved for much of the evening, had suddenly jolted to life—Faulkner’s every turn of phrase met with approving yelps of enthusiasm from attendees. Massey, however, had long since left the building.

Today, Massey remains the frontrunner for the Republican nomination to face de Blasio in the general election in November. After bringing in $1.6 million in donations between July 2016 and January 2017 and notably out-raising the mayor by $600,000 in that time, the Massey campaign repeated the feat last month—raising over $850,000 in the January-to-March filing period, more than twice the amount secured by the de Blasio campaign. (Faulkner’s campaign, by comparison, has only managed to raise around $65,000 in total thus far.) Most politicos were stunned by Massey’s haul.

Yet the picture remains far from rosy for Massey. For one, the specter of criminal indictment that hung over the mayor for much of 2016 into early 2017—threatening to blow the mayoral race wide open for Democratic and Republican challengers alike—has since dissipated, although Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. reprimanded the de Blasio administration’s practices in a March 16 letter as “contrary to the intent and spirit” of campaign finance laws.

Massey, meanwhile, has had to fend off criticisms of the way his campaign has been run, as well as his own merits as a candidate who is still relatively unknown and unproven beyond the insular world of New York real estate.

The campaign, while having raised prolific amounts of money to date, has also been spending at a significant rate. Excluding the roughly $2 million that Massey has personally lent to his bid for City Hall, expenditures have outpaced contributions—with a sizable, high-priced team of paid consultants putting a particular dent in the coffers.

As well as bringing on former SL Green Realty Corp. executive David Amsterdam to serve as campaign chief executive officer, the Massey camp has recruited the likes of Republican strategists William F. B. “Bill” O’Reilly and Jessica Proud; William Sullivan, the former president and CEO of the Ronald McDonald House New York charity and a proven fundraiser; Douglas Schoen, who worked as a pollster for former Mayor Michael Bloomberg and former President Bill Clinton; and Joshua Thompson, a Democrat (and former aide to New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker during his time as mayor of Newark) who delayed his own mayoral ambitions to join the Massey team.

“To me, nobody is going to tell me how to build or manage a team,” Massey told CO last week. “Everyone would admire an organization that is six months old and in the black, with a revenue trajectory that’s incredibly positive. I’m feeling great about where we are and the investments we have made…I’m thrilled with everybody who’s a part of our campaign. It’s worth it.”

But despite the sizable team working behind the scenes, Massey’s efforts have met scrutiny from some observers as lacking the proper focus, direction or visibility, particularly in the first six months following the August 2016 announcement that he would be running for mayor.

Massey staged his official campaign launch event in March at a kosher supermarket in Flushing (a relatively low-profile setting for such a significant announcement), and while he picked up the pace of his appearances and announcements over the course of the spring, the campaign’s outreach efforts have underwhelmed those not connected to the Massey camp.

That has raised concerns about whether Massey can successfully garner the name recognition necessary to build a coalition of voters that would enable him to genuinely challenge de Blasio, who he trailed, 59 percent to 25 percent, in the most recent Quinnipiac University poll, released Feb. 28.

“For the amount of money they’re spending, the lack of knowledge of who this guy is around the city is amazing to me,” E. O’Brien Murray, a GOP strategist who ran businessman Bob Turner’s successful 2011 campaign for Anthony Weiner’s former seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, told CO.

Then there’s Massey’s perceived inability thus far to deeply engage on the issues via concrete, developed policy proposals. While he has built his platform around four key cornerstone issues—quality of life, schools, housing and jobs—the campaign has been slow to release specific proposals beyond advocating broad ideas like more support for charter school programs, more ambitious public infrastructure developments and the construction and preservation of affordable housing on a scale far larger than the de Blasio administration’s current plans (up to 400,000 new and preserved units, according to Massey, which would double de Blasio’s present goal).

It is a state of affairs that has not gone unnoticed by the media and political observers alike, who have cited Massey’s lack of specificity on issues—and his willingness to be openly noncommittal on topics he’s yet to craft a position on—as one of the candidate’s most visible weaknesses.

“When you’re the CEO of a company, you can walk into a room and command a presence,” Murray said. “When you’re a candidate, you have to remember that people respect you, but you’re a candidate—they won’t hold you on a pedestal. You have to be able to have a coherent message about where you stand, and voters have to see you as authentic.”

Those who know and support Massey, however, claim that the campaign’s protracted approach toward developing concrete policy is merely part and parcel of the real estate executive’s transition into politics.

“He’s not a lifetime politician—he’s a small businessman,” Knakal, Massey’s business partner and one of his most active fundraisers, told CO. “Knowing Paul, he’ll research every issue to the nth degree. He’ll listen to everybody’s point of view. He’ll analyze everything and come up with positions that will be very granular on every issue.”

At a press conference in Staten Island last week, Massey told reporters that the campaign would be “coming out with policy over the next two months on everything that is important to us.” On April 17, the campaign took steps to doing just that—releasing an education plan, described as a “dramatic overhaul of the city school system,” that calls for the removal of caps on charter schools, expanded vocational training opportunities at city schools and the implementation of teacher merit pay and performance incentives, among other measures.

But with the Republican primary five months away, sources said that local party leaders are keeping an eye on possible alternatives to Massey—namely billionaire John Catsimatidis, who ran for mayor in 2013 and would be able to largely self-fund his campaign, and Richard “Bo” Dietl, the former New York Police Department detective-turned-actor and entertainment personality who announced in February that he would be running as an independent.

Dietl (who has his own real estate industry connections via friends and business associates like developer Steve Witkoff) described Massey as “a nice guy” in an interview with The New York Times last month—but added that he did not believe Massey has “the horses to run against de Blasio.” Dietl has succeeded in raising more than $390,000 in campaign donations to date, well above the likes of Faulkner. (The Dietl campaign did not return a request for comment.)

Catsimatidis, meanwhile, told CO that he has yet to decide whether he’ll run again but is currently “exploring the possibilities.” He, too, described Massey as “a very nice man…I think he has worked very hard in his life, and he wants to contribute back [to the city].” But he added that the wealthy, real estate industry donors who have so far backed Massey’s candidacy “do not make the decisions in this city.”

Massey’s chances of success, Catsimatidis said, would depend on how effectively he could reach the working communities of New York. “If you come down by my office on 49th [Street] and Third [Avenue] and you stop the next 100 people who walk by and ask them about Paul Massey, how many of them would know him?” Catsimatidis asked. “He’s got to catch fire. It’s up to him.”

Last week, after holding his Staten Island press conference at a nondescript location along the Clifton waterfront (between views of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and the Lower Manhattan skyline), Massey sat down at a nearby Italian restaurant to discuss his candidacy. Unbeknownst to many outside the campaign, he was due to undergo hip surgery the very next day, and the Staten Island visit would be his last chance to get in some time on the trail before a couple weeks of rest and recuperation.

Massey had staged the presser on the site of a proposed landing stop for the upcoming citywide ferry service that will take effect this summer—a stop that had subsequently been scrapped by the de Blasio administration in yet another example of the “inequity” that Staten Islanders face in traversing the city, he said.

The mayor himself had just kicked off a week’s worth of outreach events taking place across the borough, an effort that Massey characterized as “a campaign publicity stunt” that was being “taxpayer-funded.” Somewhat interestingly, given the distance he has kept between himself and Trump, he criticized the mayor for being “incendiary” with rhetoric that was “taunting the president” to the detriment of average New Yorkers. “We need to have a mayor who’s a consensus-builder,” Massey said, drawing on another frequently used phrase to describe himself on the campaign trail.

In response to a reporter’s question about who he had voted for in the presidential election, Massey noted that he was on the record as having written in Michael Bloomberg for president. “I thought he would be the best man,” he explained.

The specter of Bloomberg—his background as a successful businessman, his political centrism, his influence on rezoning, reshaping and redeveloping New York City—looms large as a reference point for Massey’s mayoral bid. At the Brooklyn GOP Mayoral Candidates Forum in March, Massey cited the “Bloomberg path” toward building a coalition of voters and lines that would carry him to victory. He also noted how his candidacy had secured the backing of the Independence Party—a valuable endorsement for any Republican seeking to win City Hall. (Bloomberg received the endorsement of the Independence Party three times, including in 2001, when he narrowly defeated Democratic nominee Mark Green.)

De Blasio, by contrast, has served as little more than a target for Massey’s ire over the direction of the city. Massey, who counts boxing among his hobbies, has treated the mayor like his personal speedbag; when he sat down to discuss the race so far, he discarded de Blasio’s affordable housing accomplishments to date as a remnant of Bloomberg-era policies, blamed the current mayor for exacerbating the city’s homelessness problem (“It’s a human tragedy”) and slammed his relationship with the NYPD (“[The police] are unsettled because they don’t have a leader who supports them, and the general population knows that tension exists between the police force and the mayor. That’s incredible unsettling to people.”)

He also took yet another opportunity to attack de Blasio’s work ethic, claiming the mayor “strolls into work three days a week and campaigns out of a bar in Brooklyn” and floating the idea that de Blasio doesn’t actually want the job he’s held for the past three-and-a-half years. “If he’s incompetent and distracted, it’s understandable given how little time he’s putting into the job,” Massey said. “I think he’s miscast and probably not all that happy about being mayor.”

In a statement to CO, a spokesman for the de Blasio campaign said, “Mayor de Blasio expanded pre-K for every 4-year-old and raised wages for tens of thousands of workers. Crime is at record lows, jobs are at a record high, and New York City is building affordable housing at a record pace. That is the mayor’s record, and one that New Yorkers are rallying around.”

Massey saved his most cutting rebukes, however, to attack the mayor’s ethical integrity. “Could you imagine if I was the CEO of a major business and there was a letter from the [Manhattan] District Attorney to the public saying that I had violated the spirit and intent of the law?” he said. “I wouldn’t have my job anymore. He shouldn’t have his job anymore.”

He added it was obvious that a “pay-to-play [culture] exists in City Hall” with a “for-sale sign on the city” for people looking to do business with the de Blasio administration. Massey cited the city’s controversial removal of a deed restriction on the Rivington House health care facility on the Lower East Side, which enabled landlord Allure Group to sell the building for $116 million to buyers who planned to redevelop the property into residential condominiums.

Massey, looking to draw a contrast, has pledged to not do city business or give preferential treatment to campaign donors should he be elected to office—something that may be far easier said than done, given the vast network of real estate donors who have contributed to his campaign. (Massey himself remains an employee of Cushman & Wakefield—noting that while the brokerage “remains apolitical,” C&W has “been wonderful in allowing me to pursue this passion.” He also said he remains kept in the loop with goings-on at the firm and its business.)

“I’ve taken no PAC money. I’ve taken no special interests’ money. I’m completely independent in all the good ways,” he said. “I think that’s going to be a tremendous advantage to me as mayor, because I’ll be able to make rational, smart decisions and won’t be influenced by anything other than good decision-making and a great management team.”

Hank Sheinkopf—a veteran political consultant who has worked for politicians ranging from former President Clinton to Mark Green, the former city public advocate and mayoral candidate—noted that Massey’s real estate connections notwithstanding, political campaigns in New York City “are historically heavily funded by real estate dollars.”

“The mayor has tremendous power over the real estate industry, especially development,” Sheinkopf said. “By writing a check to Paul Massey, people in real estate are saying that they don’t want Bill de Blasio in City Hall. That’s a very significant thing; people with money are saying, ‘I’ll take the risk [on Massey].’ ”

Massey has roped in contributions from a who’s who of real estate bigwigs: donors include Joseph Moinian, Darcy Stacom, Ziel Feldman, Richard and Haim Chera, Kevin Maloney, David Falk, Michael Colacino, Mitchell Steir, Ben Shaoul, Thomas Elghanayan, Simon Ziff and Aby Rosen, among others.

Another of Massey’s real estate donors is David Schechtman, the senior executive managing director at Meridian Capital Group’s Meridian Investment Sales division, who held a breakfast fundraiser for the Massey campaign last month. Schechtman said the industry’s support for Massey is to be expected given his background in the real estate world.

“How many people in the finance world got behind Bloomberg?” Schechtman asked. “It’s because they knew him.” He claimed that Massey’s top campaign issue is not real estate-related but, rather, education. “He believes there should be some form of voucher system so that not every child is destined to sit behind a desk for the rest of his or her life. He believes there should be more vocational schools.”

The candidate himself has naturally attempted to position his real estate industry experience, knowledge and contacts as strengths—particularly when discussing the need for more affordable housing.

“It’s my business; I understand it completely,” Massey said. “We need housing on a scale that nobody is talking about, and I’m going to make that happen…We’ll change the landscape in terms of housing creation in New York and build the city in a way that people will be proud of.”

While Massey has outraised the mayor by sizable margins thus far, the de Blasio campaign will benefit from the city Campaign Finance Board’s matching funds program, whereby the city matches donations of up to $175 by individual New York City residents on a $6-to-$1 basis.

Massey has chosen to opt out of the program, which is likely a financial calculation; by not receiving matching funds, he won’t be subject to the program’s campaign spending caps, which range up to just under $7 million for each primary and general election campaign (or just under $14 million total across both the primary and general campaigns combined).

That would enable Massey to raise and spend the substantial amounts of money most consider required for a Republican mayoral candidate to unseat a Democratic incumbent in New York City. “We intend to outraise [de Blasio] significantly, and I think we have an ability to do that,” Massey said, citing the record-breaking figures the campaign has been able to hit thus far. “There’s a groundswell of support for us that’s evident…The trajectory of our fundraising is excellent.”

Beyond fundraising, there are other challenges that lie ahead between Massey and his goal of becoming the city’s third consecutive Massachusetts-bred mayor. For one, Massey has spent much of the past three decades not as a resident of New York City but of Larchmont, in grassy suburbs of Westchester County. He re-established himself as a city resident in 2015, renting an apartment on Park Avenue in Murray Hill, and more recently moved into a rental near West 15th Street and Avenue of the Americas, just north of Greenwich Village.

The de Blasio campaign has already identified this as a weakness of Massey’s, poking him with statements declaring that the mayor would be happy to match his record “against any resident of New York City or Larchmont.”

“Everybody knows that you can’t out-New York me,” Massey told CO. “I’ve been in the city for 33 years. My background has given me an ability to campaign because I know community leaders in every part of the city. It’s going to be a huge asset in running the city, because I know what people are facing in every neighborhood.” He added that, these days, he’s “spending a large majority of my time in the city.” (He did not specify an exact number of days.)

Another line of attack that the Massey campaign will likely have to cope with involves their candidate’s brief—but not insignificant—run-in with the Internal Revenue Service. Massey and his wife owed the IRS around $4.1 million in federal taxes in the years following the Great Recession, as DNAInfo first reported last August—debts that Massey didn’t settle until March 2015, shortly after he and Knakal had sold their brokerage for a nine-figure sum.

Massey described himself as “an open book” when asked about the tax matter: “I’ve been verbal about any ups and downs that I’ve had in life.” He noted that Massey Knakal “struggled greatly during the recession” following last decade’s financial crisis, from which the Manhattan commercial property markets were not immune. “But I’ve had a history for 33 years of meeting all my obligations, and everybody knows that.” He said he settled his tax obligations “in full.”

Knakal offered a defense of his business partner’s previous tax issues. “Try running a service business in the most competitive marketplace in the world, when business cycles come and go,” he said. “There were probably three times in the 26 years we ran Massey Knakal that we almost went bankrupt…We had to let go of staff and do what we could to keep the lights on. We were all in, and we were going to do anything we had to do to make sure the company survived and thrived. And through all the hard times, we sold something we created from nothing for $100 million.”

“If we had some rough patches, so what? We came out the other side when some people would have folded,” Knakal added. “We did what we had to do, and Paul paid back every dollar he owed the government.”

Despite his background as a boxer, Massey will have to prepare for a fight unlike any other in his career over the following months—and an exceptionally public one at that. In addition to de Blasio himself, he’ll have to overcome decades of history that suggest knocking off an incumbent mayor in New York City (particularly a Democratic mayor in a city where Republicans are vastly outnumbered) is a near-impossible task—at least without a major, momentum-shifting series of events aiding the process.

As Sheinkopf noted, Ed Koch was able to unseat Abraham Beame in 1977, when the city found itself at arguably its lowest point of the 20th century—broke, burning and blacked out. Rudy Giuliani, meanwhile, seized the heightened racial tensions in the wake of the Crown Heights riot of 1991 to defeat David Dinkins two years later.

With the threat of indictment no longer hanging over the current administration, it seems unlikely that Massey will be able to bank on such political tumult opening up his own path to City Hall. But, as ever in politics—particularly in times like these—you can never be sure.

“The wonderful thing about having elections is that you can’t write off possibilities,” Sheinkopf said. “[Massey needs] a coalition with multiple lines on the ballot, significant amounts of money, and people need to keep believing…de Blasio is no great vote-getter either, and there are certainly enough people who don’t like him.

“The conventional wisdom thinkers,” Sheinkopf added, “just left the Oval Office after meeting with President Hillary Clinton.”