Who are the City’s Biggest Non-Landlord Landlords?

By Lauren Elkies Schram October 19, 2016 10:30 am

reprints

When you think of New York City’s biggest landlords, names like Brookfield Asset Management, Vornado Realty Trust and SL Green Realty Corp. naturally come to mind.

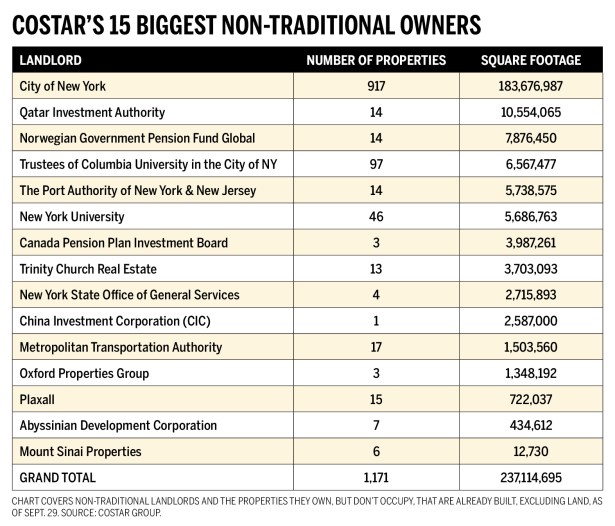

But when it comes to the city’s biggest real estate player—it is none of the usual suspects. It’s the City of New York, with a whopping 917 properties amassing 183.7 million square feet, according to data from CoStar Group. That square footage is more than five times the amount of space the city’s biggest traditional landlord (as in an entity that has a primary line of business in real estate), Brookfield Asset Management, owns.

The other biggest nontraditional property owners (of existing buildings that aren’t owner-occupied) have much smaller portfolios, according to a list compiled by CoStar for Commercial Observer. And while they are disparate, they generally fall into two categories: governments and institutions or sovereign funds

There is Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), for example, with an investment in 14 properties totaling 10.6 million square feet. And there’s Norwegian Government Pension Fund Global, with 14 properties and 7.9 million square feet; the Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York with 97 properties and 6.6 million square feet and the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey with 14 sites and 5.7 million square feet. (See chart below for the top 15.)

“I think the real takeaway, is that investors of all kinds continue to find New York commercial real estate more and more appealing given the alternatives,” said Joseph J. Sollazzo, a real estate economist for CoStar.

When it comes to the first group, government and institutions, “the goal is to advance the institution so whether it’s a church or a government, they’re not in the business of making money on real estate,” said Barry Hersh, a clinical associate professor at the NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate. “[They have] a different purpose, and real estate is just a way to meet that purpose.”

Unlike the typical real estate companies, these entities focus on whether or not they will need the properties at some point in the future. Or maybe a property has some community, historic of other value that makes its owner reluctant to sell it.

“[The] strength [of these organizations] is that they’re forever,” Hersh said. “They want to use their long-term status. They have to be really sure before they sell a property that they will never need it. They can hold them. They don’t pay real estate taxes because they are exempt. [And] they probably don’t have a mortgage.”

And while all the players we’re speaking of have some other primary business, you wouldn’t know it if you looked at the big teams involved in managing the real estate in question.

Many have in-house executives and decision-making boards, often with high-level real estate executives. Norges Bank Real Estate Management, which manages Norway’s fund, had 122 real estate employees all over the world at the end of last year, 19 of them in the New York City office, the company spokeswoman said. Carl Weisbrod, the director of the New York City Department of City Planning and chairman of the City Planning Commission, was the president of the real estate division of Trinity Church for five years. (Today, the landlord has 13 properties with 3.7 million square feet, CoStar indicates.)

At the Port Authority, Patrick Foye, the current executive director, was the president of Empire State Development Corporation under Eliot Spitzer. And until May, Scott Rechler, the chief executive officer and chairman of RXR Realty, was vice chairman, the highest-ranking New York appointee.

At New York University (which owns 46 properties and 5.7 million square feet), alumnus Larry Silverstein of Silverstein Properties serves as an honorary vice chair of the school’s board of trustees.

For out-of-town funds, they generally want someone on the ground in the local market, Hersh said. Oxford Properties Group, which is owned by the Ontario Municipal Employees Retirement System, has partnered with Related Companies at Hudson Yards. (Oxford has a stake in three existing properties, amounting to 13.5 million square feet, CoStar determined.)

It’s not exactly a surprise that the City of New York would be the biggest of all the non-landlord landlords.

“The city probably got a lot of their property through tax foreclosures, people not paying property taxes in the 1970s,” said Robert Knakal, the chairman of New York investment sales at Cushman & Wakefield. Added Hersh, “The city acquired properties when it did in rem [when property owners fail to pay taxes and the city takes legal action to gain title to the sites]. Today the city doesn’t do that. It sells the tax lien. They make a much better return on their investment.”

But just because they’re the biggest, doesn’t mean they’re the most sought after. Two investment sales brokers CO talked to who requested anonymity said that when it comes to dealing with city or state real estate, there are so many layers of bureaucracy and deals take forever.

“The city is impossible to deal with because it’s too bureaucratic,” one of the brokers said. “Deals take years and you have to have so many people provide input and sign off. It’s painfully slow and you have administration changes. As soon as the administration changes you start from scratch again.”

Then there is the second group of nontraditional landlords, comprised of sovereign funds, which resemble traditional real estate investors.

“They are investing to make money and in fact to some degree are competing with insurance companies and banks and developers,” Hersh said. “Sometimes they’re partnering with them. [They have] the same goal.”

QIA is the second-biggest nontraditional landlord on CoStar’s list due to an acquisition of a 9.9 percent interest in Empire State Realty Trust, through a $622 million investment this summer. Norway’s fund is No. 3 on the list. A 2010 mandate from the Ministry of Finance called for the fund to invest up to 5 percent in real estate, according to a spokeswoman for Norges Bank Real Estate Management.

What is evident from the list of the city’s biggest nontraditional landlords is that international funds are investing in New York City real estate. Other entities with holdings include the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (with three properties amounting to 4 million square feet) and China Investment Corporation (with one property, the 2.6-million-square-foot 1 New York Plaza).

“I think the regularity with which you find the sovereign wealth funds on this list is further evidence of international investors coming to New York,” Sollazzo said. “Many institutional investors, both domestic and foreign, have been increasing their exposure to real estate as an asset class in recent years, which makes perfect sense given the low-yield environment we currently find ourselves in. And if you look at the economic outlook for the U.S. compared to other parts of the developed world, it looks good, providing favorable growth prospects, and typically, safety from global turmoil.”

With additional reporting provided by Terence Cullen.