Archaeology Dig To Precede Construction at Historic Astoria Cove Site

By Tobias Salinger August 1, 2014 6:00 pm

reprints

The swirling debate over the 1,723-apartment, 2.2-million-square foot Astoria Cove proposal overlooking Pot Cove represents just one more stage in the transition of an area where Hallet’s Cove namesake William Hallet operated a brick factory and the father of Astoria, Stephen Alling Halsey, bought property before he incorporated Astoria Village.

The site where American Indians once congregated in intermittent villages, ferry service to Manhattan ran from the 18th century to the mid-1930s and the federal government blasted out reefs and rocks to open up the treacherous Hell Gate demands archaeological study before any construction begins on the property, according to both a required city Landmarks Preservation Commission study attached to the development team’s environmental study documents and research by the Greater Astoria Historical Society.

“That part of Queens is one of the most archaeologically significant and historically significant areas in all of Queens,” said Robert Singleton, executive director of the society. He added, “Those streets in Old Astoria predate Wall Street in Manhattan by a generation. It’s the largest, most historic area without any preservation in New York City.”

While excavation teams won’t likely find any more artifacts dating before the 1830s in the area once frequented by the Maspeth Indians of the Algonquin tribe, the possibility of such discoveries in the area that got the name “Pot Cove” from Native American pottery remains in the cove–as well as potential excavations of cisterns and privies that could shed light on 19th-century mansions which once dotted Astoria Village–merit digs on the Astoria Cove site, according to the development team’s commissioned survey by archaeologist Celia Bergoffen Ph.D., RPA.

“Sites ranging in date from early archaic through the woodland period have been identified in the Astoria Cove project site’s immediate vicinity…Testing for prehistoric remains is therefore recommended,” reads the July 2013 study. But, the 48-page report continues, the former sites of the mansions would constitute “the most significant historic remains in the areas of potential archaeological sensitivity.”

After Dutch Governor Wouter Van Twiller granted roughly 160 acres on the Astoria peninsula to Jacques Bentyn of the Dutch East India Company sometime between 1633 and 1638, skirmishes between the Dutch and the Native Americans escalated into a brutal Dutch colonist attack on the Native American village in 1644. Governor Peter Stuyvesant later awarded William Hallet 160 acres on the peninsula in 1652, and, though Indian tribesman would ransack his farm, Mr. Hallet later purchased land on the peninsula from other Native American tribes and re-established a farm and a brick-making facility on a hill near the Astoria Cove site with clay from the grounds where high-rises could jut one day.

“That hill had one of the first brick-making facilities in the region,” Mr. Singleton said. “It was one of the earliest commercial businesses on Long Island, and I would venture to say those bricks built New Amsterdam.”

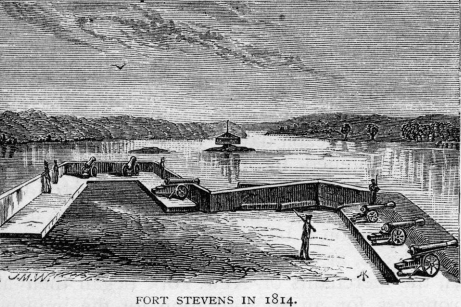

The area assumed importance during both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812—with the British controlling the Astoria peninsula and fusillading an American force in Manhattan in a 1776 cannon battle and Governor DeWitt Clinton establishing Fort Stevens to protect Manhattan in 1814 on the site of the present-day Whitey Ford Field baseball stadium.

In 1835, Mr. Halsey bought plots of land on the peninsula and began opening streets in the newly-incorporated Astoria Village, named for his mentor, the fur trader John Jacob Astor. He later established the Astoria Gas Works, built new wharves and took over ferry service to Manhattan from the peninsula. His efforts attracted new residents to the area who built their own mansions, including the Whittemores, whose house once stood on industrial lots the Astoria Cove project would build atop.

But the idea of re-establishing a ferry terminal and route to Manhattan has taken on political importance in the maneuverings around Astoria Cove, with both local Council Member Costa Constantinides and Queens Borough President Melinda Katz calling for consideration of a new ferry terminal on the site that’s a 15 to 20 minute walk from the subway.

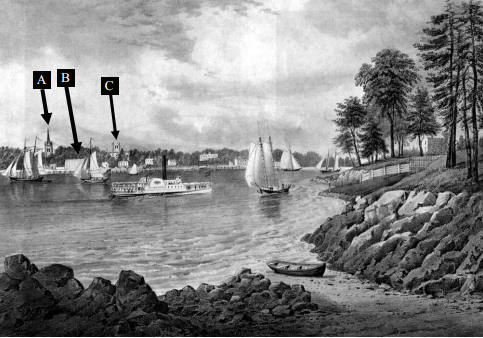

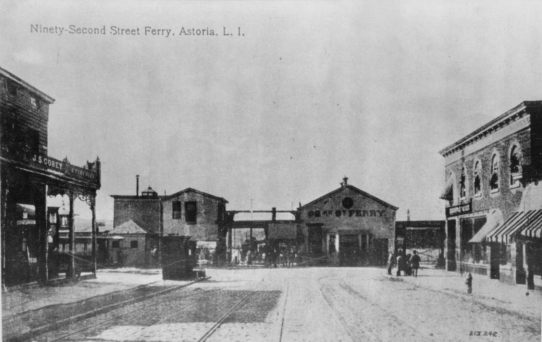

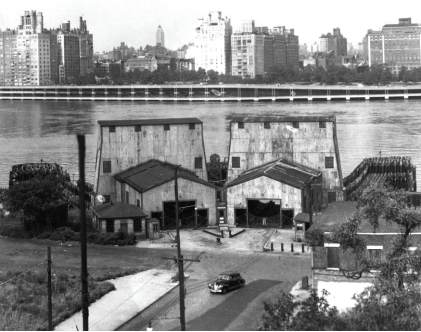

The ferry boats started as early as the 1760s or 70s before a merchant named Peter Fitzsimmons established regular trips to Manhattan in 1782, according to the historical society’s study. The ferries, which later featured trolley tracks and tidy retail shops running up to the docks, would continue operation until Robert Moses completed the Triborough Bridge in 1936 and ended all commuter boats from Astoria.

“Moses didn’t want that ferry there and people kept using that damn ferry,” Mr. Singleton said. “He chopped up the dock so that it never could come back. It was the last ferry on the East River.”

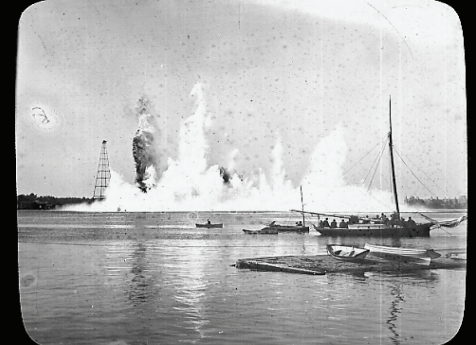

Yet, despite the frequent boats, the tidal strait north by the Astoria cove site between Astoria and Randalls and Wards Islands proved challenging to all ship pilots. Hundreds of rocks lurked in the East River at Hell Gate passage and difficult tidal currents caused “thousands of wrecks and countless deaths,” according to the society’s 2008 report.

In a passage quoted in the archaeology report for Astoria Cove, early American literary icon and prominent New Yorker Washington Irving described the danger of the passageway as comparable to a “bull bellowing” in a passage from one of his books.

“Being at the best of times a very violent and impetuous current, it takes these impediments in mighty dudgeon; boiling in whirlpools; brawling and fretting in ripples; raging and roaring in rapids and breakers; and, in short, indulging in all kinds of wrong-headed paroxysms,” Mr. Irving wrote in “Tales of a Traveller” in 1824. “At such times, woe to any unlucky vessel that ventures within its clutches.”

But the federal government undertook surveys of the rock impediments, which had names like “Frying Pan Rock” and “Bald-Headed Billy,” as early as 1848. Engineers both under contract with the government and working under General John Newton of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began blasting away at the rocks, with the Sept. 24, 1876 demolition of the 270,717-cubic-yard “Flood Rock” playing out as the largest man-made detonation until the A-bomb tests in 1945, according to the society’s report.

So the project at Astoria Cove offers the potential to change the waterfront yet again, but it wouldn’t be the first transformation at the still-industrial landscape adjacent to the Astoria Houses, which the city completed in 1951. And it won’t happen at all unless the project is approved under the Uniform Land Use Review Procedure. After that, the development team, which has agreed to make any artifacts found on the site available to researchers, according to the draft environmental impact study report, will have to sponsor a dig for any historic remains on the site of Astoria Cove.

“The draft environmental impact statement requires that the applicant continue to investigate the archaeology of the area, and the Landmarks Preservation Commission will oversee the process to ensure it meets the necessary standards,” said LPC spokeswoman Damaris Olivo in a prepared statement.