Larry Silverstein On Lower Manhattan 23 Years After 9/11

The developer, who had just taken over the lease for the original World Trade Center in 2001, talks redeveloping the site, including the latest plans for 2 WTC and 5 WTC

On Sept. 12, 2001, as New York sat smoldering under the worst attack in its history, Larry Silverstein got a call from Gov. George Pataki.

“What do you think we should do?” the governor asked Silverstein, who had the lease on the ruins of the World Trade Center.

“I don’t think we have any options,” Silverstein replied. “We need to rebuild.”

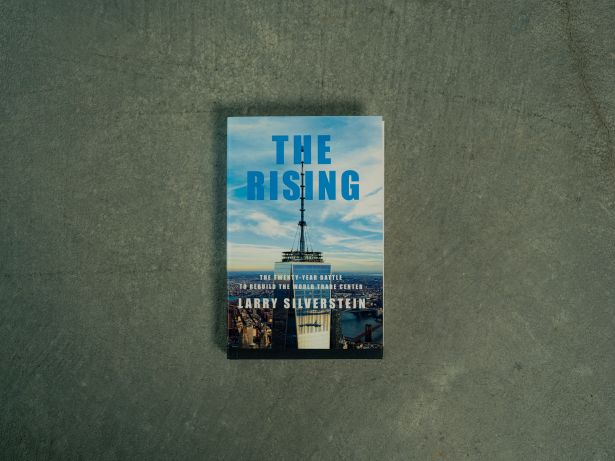

That conversation, as recounted in Silverstein’s riveting new book, The Rising, has been the animating principle of Silverstein’s life in the 23 years since.

Silverstein’s book should serve as a kind of urtext for future historians of the massively complex redevelopment. Pataki is hardly the only politician who wafts through these pages. Rudy Giuliani is there. So is Hillary Clinton. And Chuck Schumer. And George W. Bush. And many others.

Commercial real estate audiences will thrill to legends like John Cushman or Steve Roth showing up — but, unlike in a lot of books that politely cover up the feuds and embarrassments of long ago, Silverstein pulls no punches. When Roth’s Vornado won the initial bid for the WTC in early 2001, Silverstein graciously offered to let him use the financing that he assembled for the enormous project. When Roth walked away from the deal a few weeks later, Roth declined the same largesse when Silverstein asked to see the sticking points in Vornado’s contract dispute with the Port Authority, the trade center’s owner. “You’re a much more generous guy than I am,” Roth is reported to have tossed off to Silverstein.

“I think, to date, we’ve probably spent $20 billion to replace what I acquired for $3.2 billion,” a casually dressed (as in no necktie) Silverstein told Commercial Observer from his office at 7 World Trade Center last month, sitting beneath a skateboard that his employees gave him when he moved into a condo only two blocks away at the Four Seasons. (Which he built.)

“But I think when you look at everything — the problems we faced, the difficulties, all of the naysayers, and God only knows they were there in super abundance telling me when I was making all these mistakes — we look out the window today with a deep sense of pride and maybe a wee bit of satisfaction.”

He is quick to add, “I’m realizing this thing is not quite finished. We still have a couple of things to do, as I’m sure you’re aware, but when you look at what we’ve done to date, I think it’s come off well.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Commercial Observer: Reading the book, it felt that you must have pretty good political skills. Being a developer you have to appease a lot of different parties. Was that something that you ever thought about?

Larry Silverstein: Honestly, no. I think back to the early days after 9/11. The difficulties encountered among various officials made moving forward even more difficult than I thought it had to be because there was so much dissension. There was such a high level of uncertainty of what to do, how to do it, with whom to do it, who should be responsible at the end of the day.

The issues were extraordinary, determining what should be included and how. Should the new trade center have been built, or should this be a park? Or should this be a residential center? Should it be a memorial park in its entirety? Just in part? These were all issues that many factions inveighed on. And because there was no precedent, people didn’t know what to do, and it was very excruciating. So, you’re talking about political skills — I felt I was totally devoid in that capacity.

Yet, it all came together somehow.

Well, you know, it’s interesting from a legal standpoint. There were so many questions — unanswered questions, questions that surfaced. Here I was with a 99-year ground lease, responsible for rebuilding this thing because the legal documents provided that, God forbid, should there be any damage or anything, any consequence, our responsibility was to rebuild it as quickly as possible. We started with the very basic issue of who’s responsible. What has to be done by whom? The different aspects of that — it was really a massive undertaking on the lawyers’ part, and continued for years. Dealing with it all was a life’s experience.

I can imagine. What was the hardest thing?

Well, if you want to talk about difficult things, the most difficult was dealing with the families who lost their loved ones. That aspect was not my responsibility — it was the government’s responsibility. And they did a great job. But when families called and asked for appointments, I just couldn’t refuse. And so they came. They came in abundance, and kept coming, and they said, “My loved ones were vaporized, therefore there are no remains. If there are no remains you can’t have a burial. So their space is down there in this trade center — therefore there’s no place you can build.” It was tough.

I remember saying to them that I could understand their grief, their loss. I can’t fully experience it, because it’s not my loss, but I feel for you, and I have a sense of what you’re going through. But, you know, at the end of the day, we have to do what’s good for New York as New Yorkers. We have a responsibility to each other and to ourselves to do what’s right here and to put this back. And they said they can understand that, yes, but notwithstanding the fact that we have to do the right thing as New Yorkers, you can’t build anywhere on that site. The emotion was such that there was no way to deal with it other than to wish them well and express my regrets.

Another very difficult set of circumstances of a totally different type was dealing with 22 insurance companies who decided this could never be rebuilt. There would never be success here. And don’t waste our time because they would not pay a dime to rebuild this place. They said, “Get lost,” effectively. “We’ll compensate you in some fashion.” And I said, “Forget the compensation. I have no interest in that.” They said, “Come on, everybody has a price.” I said, “You don’t understand. I’m a New Yorker. I signed an agreement that said I have responsibility to rebuild. So, you don’t want to pay me, we’ll have litigation.” We sued for five years, and, then, at the end of the day, we couldn’t collect after the judgments were rendered.

They stalled?

They stalled. I remember going to Gov. Pataki and saying, “Governor, I can’t collect from them. I need your help.” He said, “Well, talk to my insurance commissioner.” I went to the commissioner, and he said, “Larry, I need the green light from the governor, I’ll get you the money.” I went back to the governor. He looks at me. He said, “Larry, I can’t do it.” I said, “Why can’t you do it?” He said, “Because I don’t want to create a bad precedent.” I looked at him and said, “Governor, we never had a 9/11 before. What precedent are you referring to?”

I was staggered by that, and I remember saying to myself, “Is it possible he has in his mind national office? … Is it possible that he thinks the insurance companies could somehow someday be helpful to him in some kind of national bid for office?” That, too, was in the book.

And then Eliot Spitzer finally came into office. I knew him, and called him, and immediately he said, [regarding Silverstein’s claims] “I’m going to get it for you.” One day he called me, said, “Larry, I’ve got all the CEOs of the insurance companies coming to my office. You need to be here at that meeting.”

Those CEOs looked at me … well, I just didn’t get a good feeling. They were furious. I just sensed their hatred for me. But, as it turns out, they did spectacularly well. It’s one of the most profitable deals they ever made, because, yes, they had to pay me $4.5 billion at the end of the day, but when you take into consideration the massive premiums that I paid for the coverage, and the fact that they had a reserve for all of this, in addition to that they earned a billion dollars on the float. From that, they had to deduct their legal fees of $200 million — so they netted $800 million on the float.

You gave them a very expensive loan. Can I ask about the current status of the site?

Well, Tower Two is the only remaining site to be developed, and that is in intensive negotiation currently with a tenant. We will be in a position to describe anything and everything you can ask when everything is concluded. [The Real Deal reported last week that Silverstein is in negotiations with American Express to anchor the building.]

I remember the Bjarke Ingels sketch for the building, and then Rupert Murdoch was in talks to anchor. That seems like a story all its own.

I think this is going to get done pretty shortly. I’m very excited. It’ll be a spectacular addition to what we have here to date.

What about Tower Five?

The Port Authority originally conceived of an office building for that site. As time went on, it became obvious to the port that perhaps the best use of that site might be residential rental housing. So we — with Brookfield — presented a bid for the site. And the Port Authority decided to choose us to develop a [1,200-unit, 40 percent affordable] rental housing plan for that site. But the present financing environment is totally out of whack. So we just have to wait until the financing world comes back again into reality and the project becomes a viable project. That’ll take a little bit of time, but my assumption is it’ll happen.

Obviously, you guys are doing life sciences and some stuff in Philadelphia and Los Angeles. How much of your attention was focused on the World Trade Center versus all these other projects?

My personal attention was focused on the trade center. I’d say 90 percent of my time was here. Maybe the other 10 percent on the rest.

My wife Klara complained to me one day, she said, “You know, you’ve got such an investment in the trade center. Wouldn’t it be wiser to diversify, spread around a little bit?” So I thought about it, and said, “Interesting thought. You’re right. Let’s see if we can diversify a little bit.” Next thing I know, I signed a lease with Moody’s for 800,000 feet here at 7 WTC. Talking to Moody’s, I asked, “When you move out of your building and into here, what do you plan to do with your building?” They said they’re going to sell it. I said, “You know what? I’ll buy it.”

And I did. I came home that night and said, “Sweetheart, we’re diversifying.” It’s 99 Church. [Across the street from the trade center, which Silverstein turned into that Four Seasons.]

What about your casino proposal?

Yeah, that’s in process. I think a determination is supposed to be made in 2025. I hope to be here. But, at 93, who knows?

I think you’ll be here. Reading the book, you talked about your first building that you bought, and it sounded like it was like a derelict building that you spruced up. Have you been tempted to do that again given that so much real estate today is just in need of that kind of rethinking and reimagining?

Well, it just so happens there is a building at 55 Broad Street in Lower Manhattan — an office building built by the Rudin family here in New York for Goldman Sachs — that is now about 50 or 60 percent vacant. They were no longer trying to improve the building for office users. We looked at it and said, “OK, let’s try to convert it to residential use.” We entered into a relationship with Nathan Berman, and we’re now in the process. I think the project is on its way to coming to fruition by the end of this year.

This area used to be overwhelmingly financial, 9 to 5, five days a week. By 6 o’clock in the evening, you could throw a bowling ball down Wall Street. Wouldn’t hit anybody, versus nobody around after 5 o’clock.

Today, you go walking down Wall Street, Broad to Water, and you’ll see that every building has been converted from commercial to residential — every one of the south side of Wall Street. It’s amazing. You’re going to see more than that happen.

And in terms of the commercial tenants, it used to be mostly financial. Now is it just mixed?

We have tech tenants. We have law tenants. I mean, you name it, we’ve got it.

Do you have a StubHub account?

Well, personally, it’s not my kind of interest. But we’ve got Uber down here, Spotify is down here. StubHub. You name it. It’s just terrific.

Tell me a little bit about Lisa Silverstein’s new role.

It’s just been a pleasure. I mean, I can’t tell you the degree of personal satisfaction that comes from having one of your own children take over a business that you started. It’s really a powerful emotional benefit. Her instincts are very good. But, then again, being around me all these years, it’s not surprising. She’s taken to it beautifully. And I couldn’t ask for better results.

Has there been any clash between you and her?

She started by telling me all the mistakes I made for the last 75 years. You know what? That’s OK. It really is, because her generation comes with new ideas and new thoughts. It brings a different perspective. I’m 93 — it’s a different world for her, and a much better world.

Max Gross can be reached at mgross@commercialobserver.com.