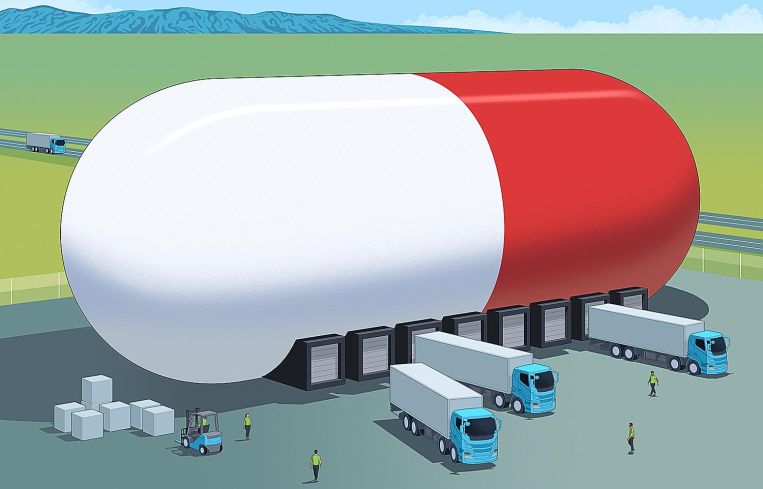

Cold Storage Is Hot — and It Will Stay That Way for A While

Changing eating habits, shifting grocer and restaurant needs, even the rise of a new class of diet pills — the stars are aligning for a once niche asset class

By Patrick Sisson February 13, 2024 9:00 am

reprints

Forget labs or data centers. The true mission critical infrastructure of American life is the 3.7 billion square feet of big, boxy refrigerated warehouses that have recently become a real estate asset of interest.

Significant changes in grocery shopping, restaurant operation, pharmaceutical storage (including new diet drugs), online ordering and meal kits, agriculture, food manufacturing and even grocery logistics all demand increasing refrigerated storage space and food prep areas, which has supercharged demand for cold storage. Colliers predicts annual growth of 13.2 percent through 2030, and real estate stalwart Related Companies last fall launched a $1 billion affiliate business, RealCold, to develop new freezer space across the country.

Cold-storage warehouses aren’t just full-size Frigidaires. Incredible technological sophistication underlies these spaces, including heated flooring — to avoid cracked surfaces from extreme cold — and multiple temperature zones for discerning tenants and different products. After all, Americans’ increased consumption of specialty coffee creamers and premium ice cream, which have high fat content, requires much lower temps than other frozen items.

“These facilities are way more complicated than biotech labs,” said Jonathan Epstein, managing partner of BGO (formerly BentallGreenOak), a global real estate investment firm that’s become a cold-storage developer and operator since launching a dedicated fund in 2021. Since big food operators are focused on cutting emissions, and the food chain produces nearly a third of the world’s carbon, some of BGO’s warehouses have sensors that can track all the carbon emissions from departing and arriving trucks. “I look at this really as food infrastructure, and less about cold storage.”

American diets have become more diverse in recent years, incorporating more fresh and healthy options, requiring more chilled and refrigerated space for organic food as well as food processing areas for packaged herbs and produce. Diet shifts and the demand for proteins and whole foods have shaped dining and grocery behavior. Much of the clamor for cold storage comes from frozen food, which has seen a huge spike in popularity since COVID. The category racked up $72 billion in sales in 2022, a third more than in 2019.

It’s a global phenomenon. Even countries like China, with a traditional everyday-visit-to-the-market culture, have seen freezer purchases spike in recent years.

“You can see it in the frozen section at the store. The number of frozen aisles has expanded,” said Rick Kingery, a senior vice president at Colliers.

This, in part, is why even the juggernaut of Ozempic and other new drugs for weight loss aren’t seen as a huge impediment to the sector’s strength. While nearly 25 million Americans by 2035 are expected to be taking these drugs, which can cut calorie intake by 30 percent, analysts believe the impact on snacking and fast-food consumption won’t significantly alter the frozen market.

There’s lots of money in these once-in-a-generation blockbuster drugs, with Goldman Sachs predicting the market could be $100 billion within the decade. But an analysis from Green Street found that if drugs like Ozempic achieved 27 million users, overall food consumption in the U.S. would decline by just 2 percent. They don’t change near- or long-term fundamental forecasts for the sector. If anything, the demand for storage of such drugs might increase demand for cold storage that much more, since Ozempic needs to be kept just above freezing before first use.

“If you’re on one of those medications, you’re still eating,” said Kingery. “And so you may be snacking less. But most of your snacks aren’t in the cold aisle.”

Siting, financing and filling a cold-storage warehouse represents a significantly more difficult challenge compared to dry, ambient industrial space. Just a handful of builders have experience in the field — maybe a half-dozen out of the hundreds of contractors who regularly do tilt-wall industrial spaces. That limits the pace of new construction and retrofits, and explains why the average cold-storage space is 43 years old.

That doesn’t even begin to reckon with the financing challenges of space that can cost more than $350 a square foot. Specialized spaces for ultra-cold food and medicine can run four times the cost of standard industrial products. These aren’t commodity spaces, either: Different uses and users require radically different layouts and designs.

Finding tenants for new buildings can also present a challenging courtship for operators, since these sites are so central to their operations. Typical cold-storage leases run 15 years, twice the length of typical industrial leases, and tenants tend to require much more on-site monitoring. And, since food production, distribution and waste account for so much carbon, tenants also have high expectations about sustainability, meaning lower carbon footprints and a better energy efficiency. Many big owners don’t build new facilities until they’re pre-leased.

The risk has scared off many potential investors. Kingery said that during the big pandemic run-up in standard industrial construction from 2020 to 2022, many cold-storage warehouses under development pivoted to traditional warehouses mid-construction. Why not take the cash at the top of the market and run instead of going ahead with a riskier asset?

“Tenants don’t show up in cold storage until the buildings are done,” said Kingery. “It’s scary to be inside a building that costs $300 or more a square foot, walls are up, roof is on, and you have no activity. ‘What have I done?’ ”

The sector has experienced the same winter of financing challenges and uncertainty as other parts of commercial real estate. Americold, one of the largest operators, had less-than-stellar earnings reports this fall and cut annual development funding from $200 million to $100 million.

But over the long term, demand isn’t slowing, and supply is unlikely to catch up due to those food and pharmaceutical trends. BGO’s Epstein estimates the nation was already short 40 percent in terms of cold-storage capacity due to changing demographics and migration patterns, and 90 percent of the existing stock needs to be replaced. With roughly 350 million square feet of space in operation now, Epstein estimates a $150 billion potential market for new development. A March 2023 report from Newmark found 9.8 million square feet was in the pipeline, a record, but not enough to overcome persistent undersupply.

“It seems like the industry’s always been that way, there’s just more use than there is space available,” said David Greek, managing partner at Greek Real Estate Partners, which operates and develops these spaces. “I think one of the reasons it’s stayed that way is that it’s just a very hard business to run. It’s much more expensive to run a third-party logistics company out of a freezer-type use than a dry use. There’s just more moving pieces. Operating and fixed costs are higher.”

That’s one reason that the sector has consolidated so dramatically. A drive toward professionalism and private equity investment has meant fewer mom-and-pop operators and more giants like Americold and Lineage Logistics, which combined run roughly 70 percent of existing freezer space. That, however, is creating opportunity. Newmark analysts suggest that this domination by a handful of big companies is presenting new opportunities for smaller, regional operators.

Cold storage has room to grow in different kinds of places as well as specific markets. Grocery stores and larger restaurant chains continue to experiment with centralizing production and distribution at cold-storage-adjacent hub kitchens, meaning smaller footprints for individual restaurants and a change in a common form of commercial leasing. That can mean savings , and shifts in restaurant leasing, if companies go from a 5,000-square-foot space with a walk-in refrigerator and freezer, and a dozen workers on shift, to a 1,700-square-foot distributed location that needs just four workers at a time.

Kroger, which has been using the Ocado robotic system for automating warehouses and distribution, found that a single cold-storage-enabled fulfillment can handle the same volume as a dozen grocery stores. When grocery retailers figure out how to improve the cost efficiency of such a system, Kingery predicts a bigger swing toward e-commerce.

In addition, new markets with growing populations demand more cold food storage. These include Sun Belt cities like Houston and Dallas. States such as Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana also have persistent need for spaces due to the prevalence of agriculture and food manufacturing. Cold storage at ports continues to be in high demand, including long-standing centers of food distribution like Philadelphia and emerging spots like Jacksonville, Fla.

The recent raft of supply chain disruptions has ramped up demand at different ports, as food firms have sought more diverse ports of call to account for disruptions. A joint venture between Americold and Canadian Pacific Kansas City seeks to develop cold-storage facilities that would consolidate cross-border trade and send U.S. meat to Mexico and then produce back north. It’s another sign of the increased importance this kind of infrastructure has on significant swaths of economic activity.

“It is the definition of mission critical,” Kingery said, “because, if you go down and you melt, the product is spoiled.”