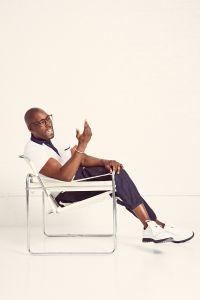

Bridge Champion: Steinbridge’s Tawan Davis on How Real Estate Can Impact Communities

By Cathy Cunningham August 1, 2023 10:30 am

reprints

Tawan Davis grew up in Portland, Ore., but his ancestry traces to Arkansas. His great-great-grandmother was born in 1896, the youngest of 11, and both her parents and grandparents were born into slavery. Later, his family worked as sharecroppers until the 1930s before moving west to Oregon — and that’s where his personal story begins.

Headed by his single mother, Davis’s family was reliant on Section 8 housing vouchers during his teenage years. He grew up surrounded by — and inspired by — strong women who ultimately taught him the profound impact that real estate can have on a community. Fast-forward to today, and Davis, 44, is CEO of The Steinbridge Group, an impact investment company with a focus on both single-

family rentals and multifamily properties, as well as public-

private partnerships.

His path to founding Steinbridge began with positions at Goldman Sachs, Prudential, the New York City Economic Development Corporation and Peebles Corporation. But, while his career has brought him full circle in many ways, leading him to a commitment to impact investing, the “numbers nerd” in him is always focused on great investment returns, too.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Commercial Observer: What was your first job out of business school?

Tawan Davis: It was with Prudential in New Jersey. The person who headed Prudential’s real estate division at the time was named Charlie Lowrey — he’s now the CEO of all of Prudential — and he recruited me. One day, he came downstairs into my little cubicle and said, “I think you should go to Europe. If you want to grow in this business, you should do an international stint.” I was 27 at the time, and I moved to London in 2006.

At the time, Prudential was doing everything from more conservative, core investing, to investing in ground-up developments and everything in between. We’d also invest in the underlying real estate companies, taking a double bottom line by participating in the real estate level as well as at the company level through a series of funds. It was an opportunistic business, and a great experience for me. I was still in London when Lehman Brothers failed in 2008, and I remember I was in Canary Wharf and saw all of these people carrying boxes with their belongings.

You never forget those images. I was a junior reporter at the time, and I vividly remember covering Lehman’s failure.

It was a really crazy time. Some years earlier, I was also at the World Trade Center when the second plane hit — so I’ve had some dramatic experiences over the years.

I was living in New Jersey at the time and I was taking the PATH train to work, and I believe it was the last train to cross under the World Trade Center that day. I was working for Goldman Sachs as an analyst, and as I started walking toward 85 Broad, the windows of the World Trade Center were shaking. I looked over my shoulder and saw the second plane hit. I got to 85 Broad and people were walking around like zombies on the 14th floor. That building is like a bunker, so there was confusion around whether we should stay or go — just total chaos. Eventually, our managing director came out and said it was time to go, and, by the time we learned this, the South Tower had collapsed.

I just remember coming downstairs and you could barely see your hand in front of your face, just pitch-black dust. I happened to come within a few feet of a woman who looked exactly like my mother’s older sister, so I followed her to a ferry that was leaving the city and heading to Jersey City. On the ferry a woman screamed, so I turned around and the North Tower had fallen. I went home and slept for 20 hours — just from sheer shock, I think.

My memories of that day are deeply painful, but it also made me fall in love with New York City. New York became a city of love in the way that people embraced each other and helped each other out, and there was this unified determination to put the city back together again. I was able to participate — several years later — in what was that resurgence of the city, but this deep determination in the city to get back on its feet and to demonstrate its resilience was something I had never seen before.

Are you referring to your role at the Economic Development Corporation, under Mayor Bloomberg?

Yes, I was focused on public-private partnerships at the EDC [beginning in 2011], helping the city to build and rebuild. I helped with the revitalization of Harlem and restructured about $1 billion worth of city properties for redevelopment. It was a remarkable experience and, frankly, of all of the jobs I had, it was my least paid but most important job. I took a humongous pay cut and worked in public service for about four years, but I met true leaders in real estate and finance, and then almost every leading real estate family or CEO in the city.

One of the fun deals I did was Citi Bike. So Citi Bike is branded as such, but it was actually financed by Goldman Sachs. So, Citibank actually pays this royalty fee to the city, almost as a lease payment, and also makes a payment to Goldman for funding the actual infrastructure.

I did not realize that!

Yes, so technically it should be Goldman Bike [laughs]. I worked with Goldman’s Urban Investment Group on that deal, and with Margaret Anadu who was there at the time [now a senior partner at the Vistria Group]. She and I became friends through it.

When you were growing up, is there anything you gravitated toward in terms of a career path?

When I was in my early teens we didn’t have much money. My mother was single and we used Section 8 vouchers to support our rent. We were religious, and there’s a Bible scripture that says the cattle on a thousand hills belong to God. I remember asking my grandmother, “How do I get a hill?! I only need one!” [laughs]. I figured all I needed was one opportunity then I could help myself, my family and my community.

Thanks to my great-grandmother, I had the sense, at an early age, that one of the most impactful ways to do that was through real estate, because real estate is this very tactile way to create wealth and opportunities. When she moved from Arkansas to Portland, she bought her own house, but also bought three other houses on the same street. Her two sisters did the same. So these three Southern women bought all these houses on the street, and every year they would drive from Oregon to Arkansas at least twice a year, pick up friends and family members, and then drive them back to resettle in Oregon. To me, that was an example of an opportunity for housing to build a bridge. My great-grandmother and her sisters would bring people, house them until they got on their feet, and then rent the houses out.

Portland went through a lot of transition, between the 1960s riots, the drug epidemic of the 1980s and the gang epidemic of the 1990s. By the time my great-grandmother and grandmother passed away, the community was not what it once was, and we sold them. But today, the 97211 and 97212 ZIP codes are two of the most gentrified ZIP codes in the country.

The third event was, my mother rented a duplex in Portland and our neighbor, Mrs. Georgia Smith, was a widow. She remarried, and was going to sell her house, but my mother asked her if we could rent the house as we couldn’t afford to buy it. Frankly, we couldn’t afford to rent either, but, from the time I was in middle school to the time I got out of college, we rented Mrs. Smith’s house with Section 8. Mrs. Smith could have sold that house 10 times over but she chose to let my mother and my little sister have a beautiful and stable housing situation.

It sounds like you grew up surrounded by really strong, and kind, women.

I can go down the line at every stage of my life and see meaningful, bright and impactful women that helped me. That certainly started with a very strong mother, grandmother and my great-grandmother, but it continued throughout my academic and professional career, luckily for me.

What did you learn from working with Don Peebles at Peebles Corporation?

He is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met. I learned a lot from working with him, but two things stick out the most. First is that entrepreneurship distinguishes itself from the institutional mindset, and I learned to think like an entrepreneur. Second, I learned there are very few limits to what you can accomplish. Don doesn’t believe in limitations, he believes that the sky’s the limit.

So he taught me — as an African American businessperson and entrepreneur — that the sky’s the limit for all of us, despite background, despite ethnicity, despite color. That was a very powerful lesson to learn up front, and in advance of starting my own business.

Talk me through the beginning of The Steinbridge Group in 2016.

We actually started by acquiring close to $1 billion worth of stabilized office buildings, not residential properties. We executed the acquisition of a series of office buildings in Washington, New York and Boston, the most widely reported of which was the restructuring and acquisition of the Watergate office building in Washington, D.C.

In 2018, it became clear to me that offices may not be a long-term growth business. I tend to be very analytical, and there were a few things that I noticed. First, WeWork was eating the lunch of many office owners. Second, in Washington, D.C., in particular, tenants were taking smaller office footprints, with new tenants taking 20,000 to 30,000 square feet rather than 50,000 to 100,000 square feet. Then — and this was before COVID — a lot of office landlords were giving people some flexibility in their work schedule. I thought to myself, “Shucks, 30 years from now, people are going to need way less office space.” And, so, in 2018, we decided to pivot toward a more sustainable business for us.

Hotels struck me as too cyclical for an early stage company, the regional mall was failing at the time and there was a shift to online shopping, and industrial was so capital-intensive with large players who had such a tremendous head start in the space. That left residential, and, as we started to research, it became so clear that the United States was perennially, perpetually and dramatically underhoused, and that was going to be true for at least one more generation.

The way that people had responded to this residential demand was by building high-end apartment towers, so you had a lot of investors coming to the U.S., going to the major metros, and building high-end residences. Well, those are the $4,000, $5,000 or $6,000 units, and the average American family makes between $50,000 and $70,000, depending on whose numbers you believe — so they can’t afford $4,000. So, the response to the housing crisis left out the bulk of the demand, which is working American families.

The opportunity we saw was to find solutions to provide better residential opportunities for working American people in the middle, if you will, because you have low-income housing tax credits and other housing strategies that address a certain portion, then you have the wealthy folks who can afford whatever they want, but it’s the working folks in the middle who get crushed and overwhelmed by the undersupply of housing choice options. That’s where we decided to focus.

Today, we have around $700 million of active developments and pre-developments around the country and that should grow to $1.2 billion in the next 18 to 24 months.

The First category is buying and rehabbing single-family homes in clusters. The second strategy is partnering with nonprofits and other landowners on ground-up developments.

As you were starting your residential business, did you tie any of what you were learning back to your family’s history with housing?

It was not clear to me at first, because I’m a nerd and was busy looking at these numbers and what made economic sense. But, as we started buying, it dawned on me that I was coming full circle, and the opportunity wasn’t just to invest, but to invent and to connect. So, funnily enough, it wasn’t the cart before the horse, it really was the analytics that led me to residential. Still, that led me back to Mrs. Smith and other experiences that I had, and we decided to put as much intention around the impact as we put around investment. That’s what changed. We knew we had to put as much intention around the impact as we were putting around the investment.

You’re partnering with PNC Bank in Philadelphia today. Talk us through the partnership.

Once we started rehabbing and building these homes for working families, our first impact was to provide high-quality homes for families that needed to move out of one-bedroom apartments, but then we started thinking about how these folks get from rentership to homeownership. It’s important, because 30 percent of the net worth of any family in the U.S. is in our homes. People who do not own a home have just lost 30 to 40 percent of their net worth at retirement.

So, we started this program with PNC, where PNC is providing mortgages and financial guidance but also providing a down payment of $5,000 to $10,000 to potential homebuyers, waiving certain fees, and waiving certain requirements. For example, a first-time homebuyer usually has to have six months of savings in the bank, and they’re waiving that requirement to get people into the homes. They are helping people to qualify for FHA loans that require a 3.5 percent down payment instead of the traditional 15 to 20 percent down payment. It’s a tremendous partnership that we think can be hugely impactful. We’re starting in Philadelphia. Our hope is to broaden that to around the country.

Cathy Cunningham can be reached at ccunningham@commercialobserver.com.