New York State Budget Looks Like a Dud for Commercial Real Estate

Development goals for the 'burbs and the much loved 421a development incentive land on the cutting-room floor in last-minute negotiations

By Aaron Short April 28, 2023 1:12 pm

reprints

New housing development will have to wait in much of New York state, and in particular in and around New York City.

Gov. Kathy Hochul announced April 27 that state leaders had reached a $229 billion budget deal nearly one month after it was due and without a plan to address the state’s affordable housing crisis. In fact, the new fiscal blueprint had little to offer a commercial real estate industry that had spent months — and millions in campaign donations to Hochul — hoping for major wins.

“I know this budget process has taken a little extra time but our commitment to the future of New York was driving us,” Hochul told reporters at the state Capitol in Albany after she and lawmakers struck a deal. “What was important was not a race to a deadline but a race to the right results.”

The spending plan includes revisions to the state’s bail laws that allow judges more discretion over setting bail, a funding windfall for the state’s transit agencies, a minimum wage hike to $16 an hour, and the addition of about a dozen new charter schools.

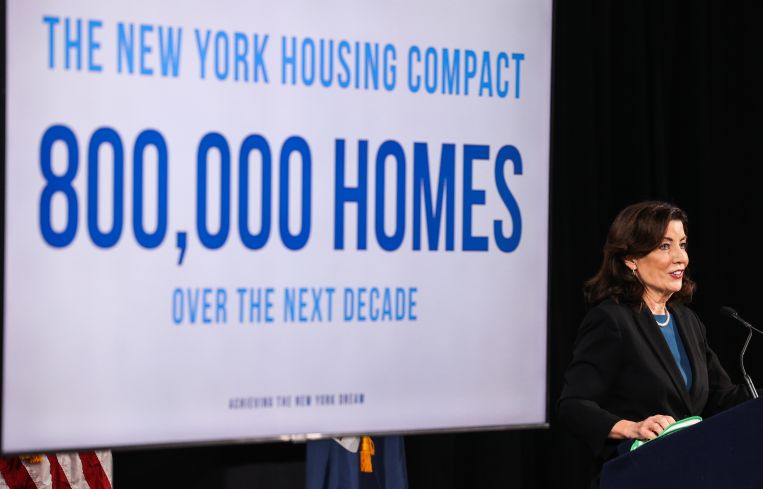

But most of the governor’s housing agenda was slowly demolished throughout negotiations. In February, Hochul outlined several measures that would override local zoning laws, incentivize development, and fund supportive infrastructure that would lead to the construction of 800,000 new homes throughout the state.

State lawmakers, county legislators, and local mayors had other ideas. They objected to her proposals one by one during weeks of negotiations.

Suburban legislators from both parties on Long Island and in Westchester and Rockland counties objected to mandates to build 3 percent more housing every three years — in some areas mere dozens of units — and to concentrate residential development near regional rail stations.

Manhattan and Brooklyn Democrats opposed Hochul’s move to lift a state limit on the floor area ratio (FAR) of new development sites, which would have enabled larger, denser apartment complexes in New York City’s most desirable neighborhoods. It would’ve also helped in efforts to more speedily convert hotels and offices into apartments, efforts that Hochul and Mayor Eric Adams — and the commercial real estate industry — support.

Hochul lashed out at the legislature for tearing down her housing ideas and doing little to replace them. “What is your plan? Because I am not done. I am coming back to say if you can do this on your own, let’s see the results,” Hochul told NY1 on May 1. “And some communities, 80 percent of communities, had to build 80 units or less. That is one apartment building.”

Real estate leaders were pining for a four-year extension of a deadline that would allow more unfinished housing projects to qualify for a lucrative tax abatement popularly known as 421a, but that too was lopped off before the final budget agreement was announced.

It was probably the industry’s No. 1 priority in the budget negotiations. Mayor Adams drew a standing ovation at the annual Real Estate Board of New York (REBNY) gala on April 20 when he called for industry support in lobbying lawmakers to revive 421a. REBNY had argued the extension would have enabled construction of 32,000 units, but lawmakers were not persuaded. Now developers are pessimistic there will be any movement to replace the abatement that lawmakers let expire last June.

“We continue to build far too few homes and our central business districts — key drivers of economic activity and state and local tax revenues — are increasingly at risk,” REBNY President James Whelan said in a statement. “Unfortunately, this budget is yet another missed opportunity by the state legislature to address these issues that are critical to our city’s future.”

On the other hand, the real estate industry did squeak by on some issues. That is, legislative inaction during the budget negotiations could count as wins. Progressive legislators’ efforts to bolster tenant protections with a statewide law capping exorbitant rent hikes and preventing property owners from evicting tenants without a good cause sputtered with the governor, and were not included in the budget.

Few housing advocates were happy with the results. The sourness marked a rare alignment between such advocates and the owners represented by REBNY.

“The budget is an embarrassment and a collective failure,” Cea Weaver, campaign coordinator with Housing Justice For All, said in a statement. “In the face of a record affordability crisis that’s driving New Yorkers out of our state in droves, our state’s leaders put their head in the sand instead of reaching a deal to protect millions of renters and provide a pathway for housing for our state’s homeless neighbors.”

Hochul was able to make major changes to state bail laws after talks with legislative leaders had stalled for weeks. Both agreed to remove the “least restrictive means” standard for all offenses, giving judges more discretion for holding defendants in jail before trial. Commercial real estate industry leaders, including landlords, had blamed increases in crime in part on the current bail laws.

The move was heavily criticized by progressive lawmakers, however, many of whom said that bail laws passed four years ago were not to blame for rising crime rates and further changes were unnecessary. Some even voted against the budget in protest.

“I will not be among those subjecting more people to the trauma that comes with being locked up pretrial,” Brooklyn Assemblywoman Latrice Walker said in a tweet. “I will not be among those who send people to death’s door at Rikers where people can wait more than a year for trial. I will not be among those who are content with sending our criminal justice system backwards.”

State leaders also delivered a bailout to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, which has been slowly gaining riders since the pandemic but still faces a $3 billion budget shortfall by 2025.

Under the deal, the state would fork over $300 million a year while the city would give $165 million per year — significantly less than the $500 million per year Hochul originally proposed — while the city’s largest businesses would see their MTA payroll tax doubled, which could amount to an additional $1 billion per year. Riders weren’t spared a fare hike, although the fare increase was adjusted from 5.5 percent to 4 percent.

In exchange, the MTA will expedite weekend and weeknight service as frequently as every six to eight minutes on several subway lines. The transit authority will begin adding more trains to the G, J, and M lines on weekends in July. Lawmakers also won a two-year bus pilot that would make one route in each New York City borough free to straphangers.

Transportation advocates took credit for securing improved subway service and the bus pilot, which was not in the governor’s original budget proposal.

“Public transit riders have been gaining power in New York for a decade,” Riders Alliance Executive Director Betsy Plum said. “Albany’s past transit funding deals left riders waiting longer, but this unprecedented budget will finally fund more frequent subway service.”

Environmentalists hailed a long-awaited measure eliminating natural gas connections in newly built buildings that was almost cut from the budget. When a Biden administration official warned about the dangers of appliances earlier this year, the idea that the state would seize gas stoves from residents’ homes prompted a nationwide backlash. The debate nearly engulfed Hochul’s gas hookup phaseout but state lawmakers resisted the pressure and new buildings will be gas free starting in 2026.

Now that the budget has been finalized, legislators will spend the remainder of the session determining if they can reach any consensus on a housing plan. When talks stalled in late March, State Senate Finance Committee Chairwoman Liz Krueger of Manhattan suggested creating a housing summit to hash out proposals for affordable housing. It is unclear whether a summit will occur before the legislative session ends on June 8.

“We’re going to start talking about housing again,” Hochul said at a bill signing ceremony in Albany May 2, although she added she was not optimistic anything would happen before the legislative session will end in June.

Housing advocates, developers and business leaders will have to wait and hope after missing out in the budget.

“We remain hopeful that in the coming weeks the legislature will put forth and pass housing policies that will finally equip the city to resolve its housing and affordability crisis” said 5 Borough Housing Movement Executive Director John Sanchez. “With housing instability being a top displacement factor for so many city residents and particularly for minorities, lawmakers must act.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated throughout as details and reaction to the budget came in.