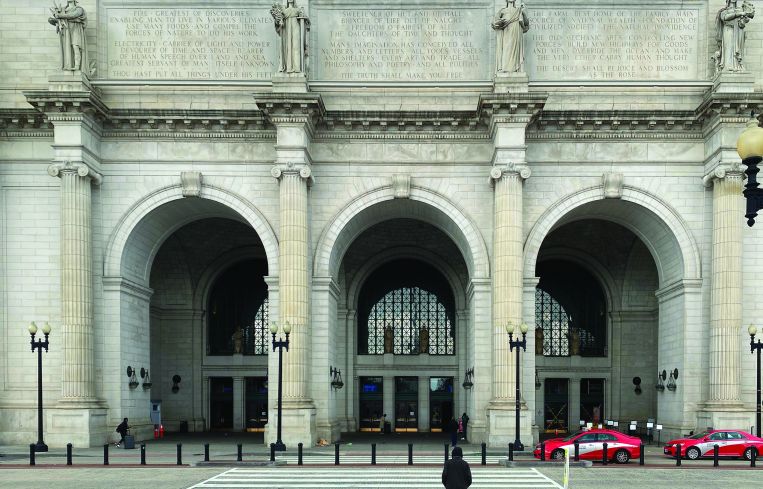

As UCC Foreclosures Soar, Mezz Lender Rexmark In Driver’s Seat at DC’s Union Station

By Cathy Cunningham October 19, 2022 9:00 am

reprints

As prolonged market volatility ensues, one of Washington, D.C.’s most treasured buildings, Union Station, is at the center of an ongoing legal battle with not two but three parties claiming rights to it: borrower Ashkenazy Acquisition Corp.; mezzanine lender Rexmark, a New York-based lender acting as U.S. agent for Korea-based Kookmin Bank; and Amtrak.

Amtrak, which utilizes Union Station as its headquarters building, filed an eminent domain claim to take control of the station in April.

But while that claim continues to play out in D.C., Ashkenazy and Rexmark went toe to toe for control of the train station in U.S. District Court in New York this past summer. Ashkenazy defaulted on its loan and was foreclosed on but then “refused to step aside,” per court documents, so the mezzanine lender sought a preliminary injunction to prevent the landlord from interfering with its contractual rights.

In a decision that may have mezzanine lenders breathing a sigh of relief, Judge Gregory H. Woods firmly sided with Rexmark’s claims, turning over control of the transit hub to the lender on Aug. 23, as first reported by Law 360.

“The lender is expressly authorized to take action to protect its interests in, and to, the collateral and collect on it,” Judge Woods said in a hearing dated Aug. 23.

The fight for Union Station apparently isn’t over quite yet, though.

A spokesman for Ashkenazy told Commercial Observer: “This matter is the subject of ongoing litigation. We are vigorously defending our rights. None of these matters have been fully litigated or determined with finality.”

Officials at Rexmark and Amtrak didn’t return requests for comment.

Both Sides of the Tracks

Market volatility has spurred a recent spike in Uniform Commercial Code (UCC) foreclosures as mezzanine lenders exercise their remedies and take control of troubled assets. It’s a ripe environment for distress, with some borrowers still reeling from COVID-aggravated turmoil, and now facing rising interest rates and an impending recession as an encore.

In the court hearing, David Scharf, chair and co-managing partner of Morrison Cohen, acting as counsel for Rexmark in the lawsuit, described the contractual rights of his client as being “clear” and “unequivocal.”

Indeed, by way of background, while a senior mortgage is secured by real property, or a leasehold interest, a mezzanine loan is secured by a pledge of equity interests in an entity that owns that property. Therefore, when a borrower defaults on a mezzanine loan, the mezz lender can foreclose on its collateral (the equity interests pledged to it) and become the borrower under the related mortgage loan.

In the case of Union Station, Union Station Investco LLC (USI) is the ownership entity at hand, owned by parent company Union Station Sole Member (USSM), or Ashkenazy.

The Union Station saga began back in 2018, when Ashkenazy, led by Ben Ashkenazy, secured a $430 million fixed-rate refinance for Union Station. Citigroup and Natixis provided $330 million in senior CMBS financing and Rexmark provided $100 million in mezzanine debt.

As the COVID pandemic wreaked havoc across the U.S. and halted foot traffic to the station, Union Station’s more than two dozen retail tenants who relied on daily commuters’ business faltered. Ashkenazy was unable to pay its full monthly debt service payments, starting on May 9, 2020, and fell into default. The CMBS loan was sent to special servicing shortly thereafter.

During a forbearance period granted by the lender, Ashkenzy took steps to pay down the loan, and also tried to secure a third-party investor to bring in additional equity. The investment, from a sovereign wealth fund, “fell through,” per court filings.

When the cash infusion fell through, Ashkenazy tried to negotiate a second forbearance period, but eventually a foreclosure auction was scheduled for January 2022. The auction was paused when, on Jan. 5, Rexmark — via Kookmin — acquired the senior loan for $358 million, but reinitiated in May and finally completed on June 14.

Cushman & Wakefield conducted the auction. Per court documents, 134 confidentiality agreements were signed and 70 parties reviewed the sale documents, but Rexmark was the only qualified purchaser to appear on the date of the auction. Per court filings, Ashkenazy permitted the foreclosure sale to “proceed without objection,” but afterwards “refused to step aside” when it came to the station’s daily operations. By that time, Ashkenazy had not paid its monthly debt payments for two years, per court documents.

“Mr. Ashkenazy and his companies are continuing to exercise control over an entity over which they no longer have an ownership interest,” Scharf said in the hearing.

Ashkenazy’s attorney, David Ross of Kasowitz Benson Torres, argued the imminent nature of any ownership changes would upset the day-to-day status quo of Union Station, which Ashkenazy has been operating for 15 years. Further, he stated that since Amtrak’s eminent domain claim was filed on April 14, Ashkenazy had been “continuously, safely and properly” operating the station.

Ross went further in likening Ashkenazy to “an expert pilot in operating a complex aircraft like a 747. They’ve been doing it continuously. They know what they’re doing. It doesn’t simply involve what any average person or any management company or any bank based in Korea or New York City knows how to do.”

He also pushed back on the prospect of the lender taking the station from Ashkenazy more generally, and the fact that Rexmark would be the ones eventually negotiating with Amtrak in the eminent domain action.

“They’re asking you to rule that they get everything completely forever and we get zero, and that they control the litigation [with Amtrak] even though it says we’re supposed to litigate,” Ross said.

Judge Woods, on the other hand, saw a “secured lender who was not paid when due and who, after a lengthy forbearance, executed its rights as a secured creditor to seize its collateral.” The judge also saw “a borrower who apparently believes that it can fail to pay its debts for years, ignore a foreclosure proceeding, snidely, sneeringly refer to that as ‘preparing papers’ and continue to act as though there were no consequences for its failure to meet its obligations.”

Woods went further in comparing Ashkenazy to an occupant of a foreclosed home who refuses to leave the premises, stating, “Using my analogy, they have gone from homeowner to trespasser. It is not the same for a trespasser to stay in the home and to make alterations as it is for the homeowner to do so and make such decisions.”

The judge also ruled the lender had demonstrated that “irreparable harm” would result in the absence of the injunctive relief sought, and so passed control of USI to Rexmark, along with the right to negotiate with Amtrak, a big part of the tangle that The Real Deal reported on in July.

All Aboard

Amtrak began its eminent domain proceeding on April 14 — an event that left both borrower and lender “blindsided” in Judge Wood’s words. “As an aside, I don’t know why Amtrak decided to act without notice to any of the players, all of whom had potentially hundreds of millions of dollars at stake,” he said.

While arguing the lender’s case, Sharf acknowledged that Amtrak’s case creates a “slightly different left turn” but also that the railroad operator doesn’t have a dog in the fight when it comes to the ownership interest of USI.

In New York, therefore, Amtrak wasn’t considered a “necessary party” with respect to the lender-versus-borrower case presented to Judge Woods. “This decision is about the managerial control over USI, not control over the leasehold,” Woods underscored.

For its part, Amtrak filed an amicus brief on Aug. 24. According to the brief, Amtrak “takes no position on the lender’s claims or request for injunctive relief relating to the management or ownership of Union Station Investco LLC.” Still, Amtrak said it disputes both the borrower and lender’s ownership and control of the leasehold interest and/or station. Amtrak has filed a motion for immediate possession, which argues that the company has the immediate right to possess the leasehold interest in the property.

Attorneys for the lenders, on the other hand, had already filed a letter on Aug. 10 stating that “Amtrak does not own Union Station. … Amtrak does not have possession of the station, does not control management of the station, and does not fund the expenses of the station.” The same letter alleges that for more than two years, it’s instead been Rexmark which has been making payments for the operating expenses of Union Station.

As an added curveball, Amtrak’s eminent domain claim values the station at only $250 million, a steep decline from the station’s estimated $1.24 billion value when Ashkenazy’s 2018 refinance took place. Court filings show that Rexmark and Ashkenazy both value the station today at somewhere between $700 million and $1 billion.

Sources familiar with the Union Station dispute said that the eminent domain action is a lengthy process that could take years to resolve. But, in the meantime, the contractual rights of the property’s mezzanine lender have been enforced, and Rexmark is in the driver’s seat at Union Station.