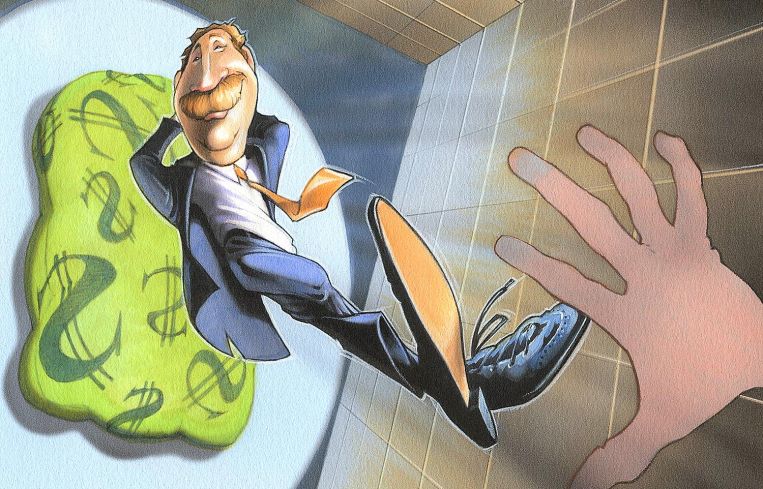

Why Some Developers Seem to Fall Backwards Into Success

By Adam Bonislawski October 6, 2021 1:00 pm

reprints

In 1991, developer Ian Bruce Eichner defaulted on a $250 million construction loan for his office tower 1540 Broadway. His company Broadway State Partners went bankrupt the following year and sold the building to Bertelsmann for $119 million. He lost the Midtown high-rise CitySpire to the Bank of Nova Scotia that same year.

Some 17 years later, the 2008 financial crisis hit. Eichner’s massive Las Vegas resort and casino development, The Cosmopolitan, sank with the rest of the market and lender Deutsche Bank took over the property.

A decade after that, Eichner found himself doing battle once again, this time at his Flatiron District condo building Madison Square Park Tower, with Madison Realty Capital stepping in to provide the project a $167.5 million first mortgage loan that allowed the developer to resolve his disputes with partners Fortress Investment Group and Dune Real Estate Partners.

All of which is a windup to the following question: Just how many chances does a person get in the commercial real estate biz?

For developers who’ve proved they can pull off big money-making projects (which Eichner, to his credit, has, with developments like his Miami condo complex, the Continuum), the answer would seem to be as many as they want.

It’s not like Eichner is alone, after all.

In the 1990s, Harry Macklowe defaulted on some $100 million in loans and was forced to sell his Hotel Macklowe property. When the 2008 collapse hit, he lost almost $10 billion worth of buildings when he couldn’t cover the bridge loans he’d used to finance the $7 billion collection of office towers he bought from Blackstone the year before. Four years later, he was back building supertall condo tower 432 Park, which became one of the most-hyped and highest-priced residential developments in New York City.

Or, take developer and bon vivant Aby Rosen, who a few years back was able to put together the money to buy (at what many now consider too steep a price) the Chrysler Building, even as he was struggling to hold onto his prized Lever House property (which he has since let go) and squabbling with partner Vanke US over their Midtown condo development at 100 East 53rd Street.

Real estate is a cyclical business, and getting stung by a down cycle just goes with the territory, suggested RXR Realty President Michael Maturo.

“Sometimes you have a good project with a good sponsor, and you can’t get it through the cycle,” he said. “You can’t get it designed and constructed and leased or sold all in the cycle. It’s inherent in real estate. There’s just so much that can go the wrong way.”

Stay in the game long enough, in other words, and eventually you’re going to have a flop, or several.

The key to surviving to fight another day is how you comport yourself during the collapse. Work constructively to reach as good an outcome as possible, and lenders and investors may well work with you again. Dishonesty, on the other hand, can be the kiss of death.

“The No. 1 rule when dealing with banks: If you are honest, if everything you do with them is honest to a fault and the bankruptcy is a result of something beyond your control … and you continue to work with them openly and honestly, you generally will live to work with that same lender again,” said David Schechtman, senior executive managing director at Meridian Capital Group.

“For me, as a counselor for clients, if I believe that a counterparty has a reputation for lying and stealing and doing fraudulent things, I would tell a client, ‘life is too short,’” said Jay Neveloff, a partner at Kramer Levin.

Neveloff’s most famous former client, Donald Trump — who does not, shall we say, enjoy a universally acknowledged reputation for honesty and rectitude — also happens to be one of real estate’s most famous comeback artists.

In the early 1990s, Trump lost three of his Atlantic City casinos and The Plaza Hotel to bankruptcy. By the mid-2000s, he was back building a Chicago high-rise behind financing from Deutsche Bank. When that project went south during the 2008 crisis, he and the bank ended up in court fighting it out. Nonetheless, Deutsche Bank lent to him again throughout the 2010s and only recently announced that it would be cutting ties.

That said, the Trump approach isn’t necessarily recommended.

Fighting rather than working with your lenders as a project falls apart isn’t quite as fatal as outright deceiving them, but it doesn’t exactly improve your future prospects, said Marc Warren, principal at Ackman-Ziff Real Estate Group.

“When you’re suing lenders, that’s a pretty bad set of facts that can keep you from getting financing, both equity and debt, in the future,” he said, though he noted that there certainly are developers who have done it and lived to build again, adding that “many people seem to have short memories or other motivations.”

“Lie to a bank? Be difficult for stupid reasons? That’s a big no-no,” Schechtman said. “You won’t be using that bank again. And the industry is small.”

At the end of the day, though, developers looking to come back after a bust have one overriding factor in their favor, especially when it comes to doing business in New York City: Banks and other investors have to get money out the door, and there’s a relatively limited pool of top-shelf developer talent.

“It’s extremely difficult to see a project from inception through to completion,” said Aaron Appel, senior managing director at Walker & Dunlop. “There are lots of different issues that arise along the way, and, while lots of people have built buildings, it’s a much smaller pocket of companies that have built high-quality buildings that can stand the test of time. Groups that have been able to do that are able to attract substantial amounts of capital.”

“People who say, ‘Oh, these guys, they’ve had losses, I don’t want to go anywhere near them’ — they aren’t going to be active players in New York real estate,” Neveloff said.

It’s a bit like being an NFL head coach. Once you’ve ascended to that level professionally, you have some staying power.

“Look at Rex Ryan,” Schechtman said, referring to the former New York Jets coach and his inglorious tenure. “It’s rarified air. Ultimately, it’s not easy, and it’s a small world.”

(For those not intimately familiar with the travails of New York’s junior football franchise: The Jets fired Ryan in 2014 after a 4-12 season. Two weeks later, he had a new job as head coach of the Buffalo Bills.)

“Certain types of people have some really unique skill sets and they are able to do things that become very attractive for capital to partner with,” Maturo said. “A lot of these players have great business personalities and they are great salesmen, and they have a great knowledge base and are good at understanding trends, and seeing what the next thing is and what the next great location is ahead of when it happens.

“Sometimes they are right on and they make a killing. And sometimes they’re not wrong, but maybe too early, and the pieces don’t come together,” he added.

Attorney Adam Leitman Bailey cited Macklowe’s history of booms and busts.

“He hits bottom, but he has incredible charisma and charm,” said Leitman Bailey, who represented Macklowe’s ex-wife, Linda, in the couple’s divorce proceedings. He attributed the developer’s comebacks to his ability to envision and package deals that capture the imaginations of lenders and investors.

“They would love the site, they would love his plans, they would love his drawings,” he said. “And they like his name. His name does sell.”

Another factor in Macklowe’s favor is that he “builds very well,” Leitman Bailey said. That aspect of the developer’s reputation could take a hit, though, given the ongoing controversy at 432 Park where, in September, the condo board filed a $125 million suit alleging construction flaws, including flooding, electrical explosions, and noise and vibrations coming from the building’s mechanical systems.

Eichner and Macklowe “are smart, creative guys,” said Neveloff, one of the few sources contacted who would speak on the record about specific developers’ ups and downs — itself a reflection of the fact that no one can ever be truly counted out. Eichner and Macklowe did not reply to interview requests. Rosen declined to comment.

“That doesn’t mean that they are always right, and that doesn’t mean that their vision doesn’t sometimes get clouded by their optimism,” Neveloff said. “But that is why they are great developers, because of that optimism. And it’s up to the lender or the equity investor to say, ‘You know, I think you’re being a little too aggressive.’”

Of course, lenders and investors have incentives of their own that can drive them to take a chance on a developer with a tumultuous past.

“What basically allows people who have had numerous debacles to get financing is lenders’ and investors’ short memories, greed, and the competition in the market to get the money out,” said Ackman-Ziff’s Warren. He struck a more skeptical note regarding second chances.

“I’d like to think people can learn from their past problems, but I’m not really convinced that that is the case,” he said.

“I’m not going to name projects, but sometimes you have seen foreign capital that is more outside the mainstream that will take risks just to get into the market and not really do enough due diligence on the sponsor or the project itself, and they get in trouble,” RXR’s Maturo said. “They don’t understand the market. They are just following a hot market. There is what they call ‘hot money’ that needs to find its way out of one place and into another.”

“There are lots of different reasons why you have capital that goes into something without really understanding it or doing enough due diligence in terms of the decision-making process,” he said. He noted, however, that this isn’t a particularly common phenomenon.

Another fact to consider, Schechtman said, is that even when a development goes under, there is sometimes still money to be made.

“Nobody wants bankruptcy, but oftentimes it is a vehicle by which you can hit the pause button,” he said. “I’ve seen bankruptcies where the borrower and the lender emerge and they actually go ahead and still manage to profit.”

Sometimes those profits are reaped by someone else down the road.

Deutsche Bank invested $4 billion with Eichner to build The Cosmopolitan. It took over the property in 2008 and sold it to Blackstone in 2014 for $1.7 billion. In the last week of September, the private equity giant announced it was selling the Vegas hotel and casino for $5.7 billion, making it the most profitable sale of a single asset in Blackstone’s history.

A total bust or a wild success? Depends on who you’re asking.