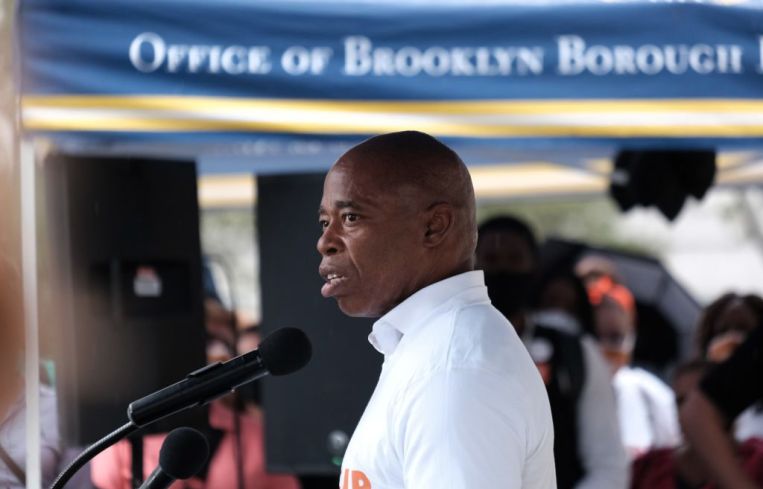

Eric Adams Wants to Turn Distressed NYC Hotels Into Supportive Housing

Hotel, motel, Holiday Inn: The Democratic mayoral nominee plans to convert all of them into affordable housing

By Aaron Short September 22, 2021 9:59 am

reprints

Eric Adams pitched turning distressed hotels in New York City into supportive housing to tackle a homelessness crisis that has worsened during the pandemic.

The Democratic nominee for mayor laid out his plan Monday to convert scores of defunct and underused hotels, primarily located in the outer boroughs, into 25,000 units of permanent affordable housing, noting that it would be cheaper to fix up hotels than build apartments from scratch.

“The combination of COVID-19, the economic downturn, and the problems we’re having with housing is presenting us with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Adams said in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, outside a shuttered hotel. “We can use this moment and find one solution to solve a multitude of problems.”

Six weeks before Election Day, Adams reintroduced his housing plan that he first floated in February, when the rate of homelessness reached a peak of 20,822 single individuals and a second wave of COVID infections buffeted the city. (Adams is the heavy favorite since Democrats far outnumber Republicans among registered voters.)

Less than half of the jobs in the leisure industry had been recovered as of March 30, and as many as 200 of the city’s 700 hotels had been temporarily or permanently closed — making a handful of non-union, low-wage hotels scattered across the city a ripe target for politicians.

Then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo included a provision in his State of the State address to convert vacant hotels and offices in Midtown for affordable housing in January. A month later, Adams complained about the “oversaturation” of lodges in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, and proposed the city adapt them for residential use.

By June, state lawmakers passed a bill allowing the state to purchase these properties and attached $100 million to fund the initiative.

But that money could dry up quickly. Hotels in Manhattan sold for a median price of $275,000 per unit by the end of 2020, Bloomberg reported.

Adams wants the city to chip in more of the cost to get the conversions going.

“You need the city to invest city dollars to acquire and convert these units,” he said. “The numbers just make sense.”

New York City has used hotels as temporary homeless shelters before. In 2015, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a plan to create 15,000 units of supportive housing over a 15-year period. But some sites ran into vehement local opposition. Elmhurst, Queens, residents protested a shelter the city opened in the former Pan American Hotel in 2015 and Maspeth demonstrators forced the city to scrap its plans for a shelter four years later.

When the pandemic started last spring, the city moved thousands of unhoused individuals and families from shelters into boutique hotels as occupancy rates plummeted. By June, the de Blasio administration reversed course and started moving 8,000 homeless people out of hotels and back into shelters after complaints from neighborhood residents.

Adams’ plan has the support of the city’s powerful hotel workers union, which has been simultaneously pushing a special permit that would significantly limit the construction of new hotels citywide like those Adams has decried.

“Even before COVID drastically reduced tourism, we saw unchecked hotel overdevelopment jeopardize good-paying jobs and community safety. And now, with thousands of rooms to be built, but no customers to fill them, the problem has only gotten worse,” said Rich Maroko, president of the New York Hotel Trades Council. “[Adams’ plan] is exactly the type of common-sense approach we need to better protect the safety of our communities and economic resurgence of the hotel industry.”

Vijay Dandapani, who represents the city’s beleaguered hospitality industry as president and CEO at the Hotel Association of New York City, said as long as the city refrains from using eminent domain to seize properties, hotel owners shouldn’t have any concerns about Adams’ idea.

“Owners would have to be incentivized to either sell or participate in the conversion process and, to that extent, the Adams proposal is laudable,” he said. “The outside boroughs do lend themselves more readily for that as the acquisition and conversion costs are likely to be lower.”

But some housing advocates say that for Adams to reach his goals, he cannot ignore vacant boarding houses in the heart of the city.

“You really need Manhattan in that calculus, but the policy to target vacant and underperforming hotels is a really smart policy and very timely,” said Brenda Rosen, president and CEO of Breaking Ground, a supportive housing nonprofit. “We really think it’s a smart idea and it’s one that is not going to come along again for a long time, as New York recovers.”