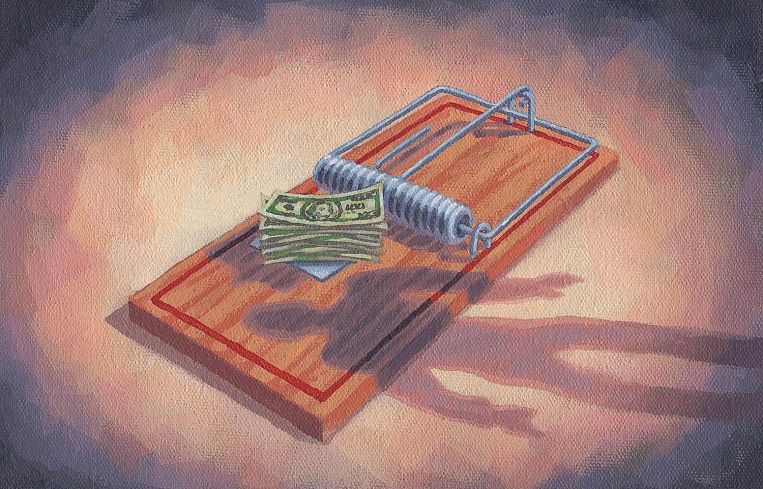

Margin Calls During the Pandemic Prove Risk in Repo, Warehouse Lending

Each line became a kind of leverage trap for borrowers

By Adam Bonislawski May 3, 2021 9:00 am

reprints

As far as cautionary commercial real estate tales from the COVID-19 crisis go, TPG Real Estate Finance Trust (TRTX) was perhaps the poster child for distress in the early days.

When the onset of the pandemic roiled markets in March of last year, the nonbank lender was besieged by margin calls that it ultimately met by selling off some $1 billion in assets, unloading the bulk of its CRE debt.

While TRTX was recapitalized in late May with $325 million from Starwood Capital Group, there was a point early in the pandemic when it appeared possible the firm might even have to close its doors, with CEO Greta Guggenheim (who stepped down at the end of March 2021) noting during its Q1 2020 earnings call that it might not have the liquidity needed to continue operations.

TRTX wasn’t alone. In March 2020, ag mortgage investment trust sold $880 million of bonds to cover margin calls. Invesco Mortgage Capital, meanwhile, announced the same month that it was not able to cover margin calls made by its lenders. In April, it announced its lenders had sold roughly $3.5 billion of the securities it had pledged as collateral.

Other mortgage REITs, including new york mortgage trust, had trouble making margin calls that came in at the beginning of the crisis and had to ask their counterparties for forbearance. Ladder Capital also received margin calls from some of its lenders in March 2020, though the company said it was able to meet them with available cash on hand.

The pandemic pulled the curtain back on the risk inherent in some finance companies’ reliance on repo lines and warehouse financing for leverage in order to provide lower cost of capital to their borrowers. A year later, the end of the outbreak and the start of a more normal economy are, if not here exactly, then at least in sight. The question then is: Will finance firms burned by their use of leverage return to circling the flame?

The short answer: Almost certainly. The slightly longer answer: Maybe that’s OK.

“If you look at what is going on today, [leverage] is very much back in the system,” said Josh Zegen, managing principal and co-founder of Madison Realty Capital.

One difference between now and pre-pandemic times, he noted, is that previously, while repo line and warehouse financing leverage was available across most asset classes, today it is typically reserved for more desirable segments like multifamily and industrial.

Within those strong-performing segments, it is essentially business as usual, Zegen said.

“Multifamily, in particular, is very much back exactly where it was before, in terms of leverage providers providing 75 percent or more leverage to lenders,” he said.

“A lot of that is sort of emboldened by the fact that the [collateralized loan obligation] market is back,” Zegen added. “So, a warehouse lender feels comfortable that their line is going to be paid off by a CLO execution.”

John Worth, executive vice president for research and investor outreach at Nareit, a REIT industry organization, said that mortgage REITs have actually deleveraged considerably since the 2008 global financial crisis, with the median leverage ratio of mortgage REITs now roughly half what it was in the years preceding that downturn.

Boyd Fellows, founder and managing partner of ACORE Capital, said that while fear of warehouse line leverage contributed to the decline in public mortgage REITs’ stock prices early in the pandemic, the actual stress due to margin calls was far less than was expected. In fact, he said that the crisis has served as a sort of stress test for the warehouse lending system, one that he said it had passed handily.

Where firms ran into trouble during the early days of the pandemic was largely due to leverage taken on via lines of credit leveraging securities, often referred to as “repo lines,” as opposed to “warehouse lines,” which are collateralized with whole loans, Fellows said.

Repo line collateral is made up of securities, which are liquid, and for which there are readily available market prices — CMBS bonds, for instance. This means that when a shock like the COVID-19 pandemic hits and drives down the value of that collateral, that decline in value is readily apparent. That triggers the repo lender to make a margin call to account for the decline in value, with the lender quickly selling the collateral if the margin call is not met.

“In the case of repo on securities, it’s a programmatic process,” Fellows said. “It is uncommon for much, if any, latitude to be granted by the repo lender.”

Such was the situation that firms like TRTX found themselves in a little over a year ago. COVID-19 shut down the economy overnight, crushing the value of the real estate securities they had used as collateral for their repo lines. AG Mortgage Investment Trust sued its repo lender, Royal Bank of Canada, to stop it from selling the securities it was holding as collateral, with the two parties settling at the end of May.

Worth said that also contributing to the difficulties that some mortgage REITs experienced was the fact that while the Federal Reserve moved quickly to buy agency residential MBS to support that market, it was slower to launch an agency CMBS purchase program.

“The Fed stepped in with purchasing programs, but the Fed did not include initially agency-backed [CMBS] in those purchase programs,” Worth said, noting that this was, perhaps, because these securities had not been a major contributor to the 2008 crisis.

“What happened was that having been sort of left out of the Fed purchase programs, [CMBS] was one of the few securities that didn’t have an easy source of market liquidity from the Fed, and so there ensued a period of around two weeks with a lot of market turbulence, where spreads widened, the repo market really froze up for those assets, and the mortgage REITs that held them really had some difficulties.”

While warehouse lines are also commonly used by real estate finance firms to take on leverage, they operate in a fashion that proved less problematic for borrowers during the pandemic than the repo market.

Fellows noted that warehouse lines importantly include covenants, which require warehouse lenders to demonstrate that the individual assets underlying the loans have degraded in order to make a margin call.

“They have to show, for instance, that net cash flows at a particular property have declined,” Fellows said. “And these things normally happen over long periods of time. Tenants move out, they can’t get a lease signed. But they can’t [revalue the loan] based on the general market.”

That provided warehouse lenders and borrowers some breathing room to work things out, he said. Even in the case of hotels, where Fellows noted publicly available occupancy data provided banks with the legal standing they needed to make margin calls on collateral comprised of hotel loans, lenders were, by and large, accommodating, Fellows said.

“As this was unfolding over March, April, May, June, I was thinking that investors are going to be even more concerned about the use of warehouse lines,” he said. “But the warehouse line market actually was quite resilient. Our warehouse lenders were reasonable, thoughtful, intelligent and calm.”

He suggested that the experience could actually lead to an increase in the acceptance and use of warehouse lines, rather than a pullback.

Zegen noted, though, that while it was true that repo lines were the major source of REIT troubles, the specter of a downward revaluation of warehouse line collateral put pressure on the overall market, as a number of firms withdrew commitments and term sheets in the spring to preserve liquidity, in case they needed to pay down their warehouse line leverage.

The nature of the crisis also likely contributed to the willingness of warehouse lenders to work with their borrowers. By and large, the problems with their loans weren’t due to any underlying economic weakness, but stemmed from the shock of a black swan event that most expected would resolve in a relatively short amount of time. It made sense to cooperate.

That same suddenness and unpredictability also underlay the difficulties in the repo market, where a decline that, in a more typical downturn, would occur over the course of months happened essentially overnight.

Zegen said that, in his view, firms that were highly leveraged pre-COVID were vulnerable to more mundane hiccups than a global pandemic anyway.

“I thought that the margins were very thin,” he said. “When you’re lending at LIBOR 300 and borrowing 75 to 80 percent of the capital at LIBOR 200, that’s pretty tight. I think one of the problems was, there was no room for error, whether it be through a capital market change, an interest rate change, or any shock to the system.”

“People,” however, “have a very short memory,” Zegen said. “So, it’s already changing back to what it was.”

Leverage isn’t as readily available for asset classes like hotels, retail or office, but segments like industrial, and especially multifamily, have seen a return to pre-pandemic leverage, he said. In some cases, Zegen noted, conditions are even more favorable than they were before COVID-19.

“If it’s multifamily in, say, South Florida, that may be a better asset to leverage as a lender than it was even going into the pandemic,” he said.

Eventually, repo and warehouse leverage will likely return even to currently less-favored segments, Zegen said. “I think things always go back to the mean.”

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)