Eli Broad Was LA’s Great Champion, and the Catalyst to Its Evolution

The billionaire philanthropist built two Fortune 500 companies before leading massive efforts behind civic developments

By Greg Cornfield May 6, 2021 8:05 am

reprints

It’s impossible to imagine today’s Los Angeles without Eli Broad, and it’s just as difficult to quantify the impact he had in helping to reshape what became his adopted hometown for more than a half-century.

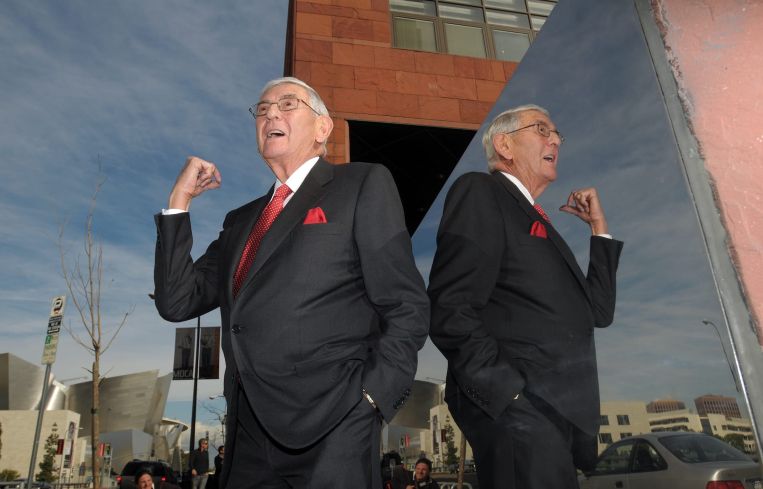

The billionaire philanthropist died last week at 87 years old after becoming, perhaps, the largest individual force and the most effective person behind the city’s modern evolution. While few people ever get the chance to carve out a strip in the skyline of a metropolis like L.A., Broad led efforts that helped revitalize an entire corridor downtown, and catalyzed unprecedented cultural development.

“Eli Broad, simply put, was L.A.’s most influential private citizen of his generation,” L.A. Mayor Eric Garcetti said in a statement.

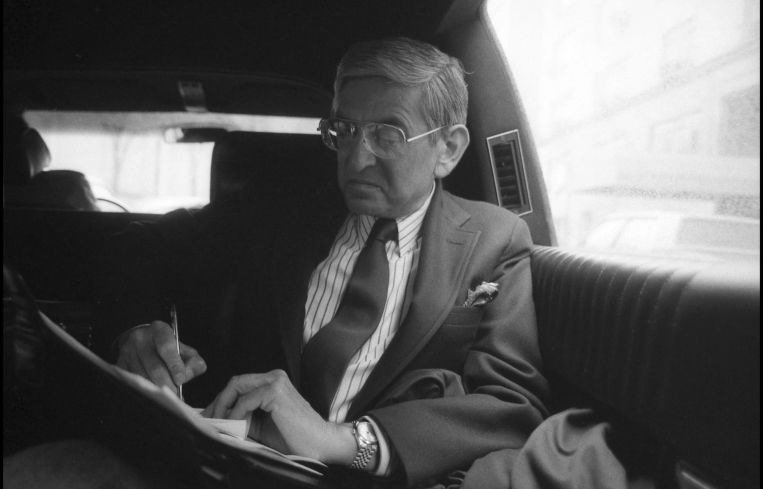

Broad made a fortune twice over. First, he and business partner Donald Kaufman started what would become the powerhouse development firm KB Homes. Their key was constructing houses within a streamlined process that didn’t include common basements, which introduced an affordable alternative for young families around the country. In 1971, Broad used that success to acquire SunAmerica, a subsidiary of insurance giant AIG, which he turned into a retirement savings firm that later sold for a cool $18 billion in 1999.

And still, with that said, Broad will be mostly remembered for how he used those fortunes to improve the city he loved.

With an estimated net worth that outstrips most cities’ yearly budgets, Broad had more leverage than most politicians. He made waves for using his wealth to make his way onto, or out of, influential trustee boards, and for diving head-first into contentious education reform efforts. A 2003 LA Magazine cover asked, “Does Eli Broad own LA?”

“Love him or hate him, we stand in the shadow of his vision of a better world,” David Ambroz, former president of the L.A. City Planning Commission, said via email “Harnessing his privilege, especially later in life, he labored to create and improve. Walking through his museum, by his Concert Hall, and by the schools he supported — Broad leaves a deep imprint that defines our days.”

Zev Yaroslavsky — who was a member of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors for 10 years, and the L.A. City Council for almost 20 years — told Commercial Observer that Broad’s impact was huge because of his civic leadership.

“He was one of the most consequential civic leaders and philanthropists, and I don’t think it can be overstated,” he said. “He invested his wealth, not in profit-making enterprises, but in civic projects. The thing that differentiates him from so many other philanthropists is that he had a civic conscience. Not everybody agreed with his civic views, but, through his sheer force of persistence and vision and intellect, when he spoke, people listened.”

Eli and Edythe Broad moved to L.A. nearly 60 years ago and almost immediately planted a flag in the art scene. They helped found the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA); played an active role at the L.A. County Museum of Art (LACMA); and donated millions to support public museums around the region.

Their goals were ambitious: to establish L.A. as a world-class, cultural hub with the likes of New York and Paris, and to share their personal collection with the world. As modern art purveyors, the two grew a collection of works that became one of the most prominent holdings of post-war and contemporary art in the world. And they since established The Broad Collection and The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation to lend their library of iconic pieces around the world.

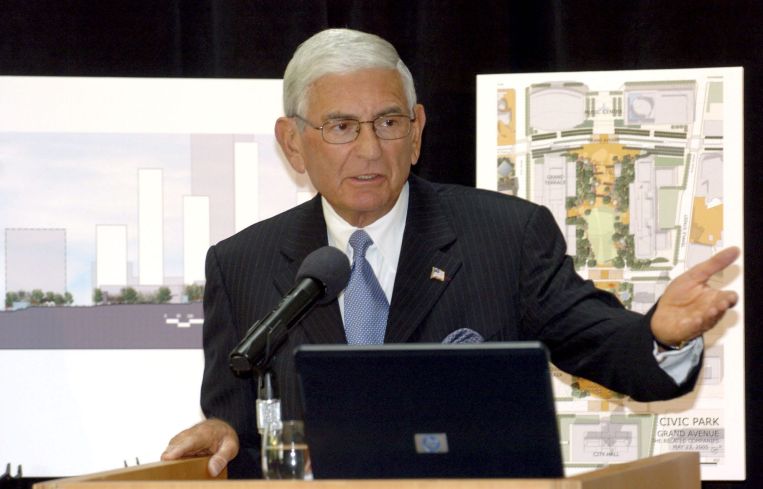

Broad also led the transformation of Grand Avenue in Downtown Los Angeles. He was a founder of the Grand Avenue Committee that brought together county and city leaders around a common goal of bringing downtown back to prominence, and strengthening the city as a hub for culture and arts.

Outside of downtown, Broad has also donated nearly $70 million to LACMA over the years, helping to revitalize the landmark museum and expand its campus, which also led to The Broad contemporary art museum (BCAM) at LACMA in 2008.

“No one spent more time and energy promoting L.A. as an art capital than Eli,” Michael Govan, CEO and director of LACMA, said in a statement. “His impact on L.A. will be felt far into the future. Though he will be dearly missed, his legacy lives on in so many places including BCAM at LACMA, continuing the Broads’ vision of making great works of art accessible to the public.”

Broad also romanticized about bringing the city of L.A. together — figuratively and literally. He often said L.A. is 100 neighborhoods pretending to be a city. Broad wanted to change that narrative and establish L.A. as a cohesive hub, as well as build physical places that bring people together to celebrate their city’s culture and diversity.

In the 1990s, Broad spearheaded a campaign to fund the Walt Disney Concert Hall project on Grand Avenue. After helping to raise hundreds of millions of dollars, he is credited with rescuing a failing project. He also bailed out MOCA on Grand Avenue from financial obscurity with a $30 million donation in the early 2000s.

Broad said his and Edythe’s hearts are on Grand Avenue. Today, it is home to the Ramón C. Cortines School of Visual and Performing Arts — another initiative led by Broad — the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Walt Disney Concert Hall, MOCA and Grand Park, which are some of the most notable architectural achievements in Los Angeles over the past three decades. The corridor also includes The Broad Museum, which opened across the street from the concert hall in 2015 as a permanent home for the Broads’ personal collection, which features works from artists like Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Damien Hirst.

“His fingerprints are all over the cultural landscape of L.A.,” Yaroslavsky said. “He didn’t do it alone, but he also transformed the definition of civic responsibility in L.A. […] When civic leaders who have made their wealth look how to best establish their legacy, it’s Eli Broad who has set the bar. He set the bar quite high.”

There are other notable donations by the Broads, including more than $20 million for the Richard Meier-designed Eli and Edythe Broad Art Center at UCLA. Broad also helped fund a ballot measure in 2002 that would have helped bankroll a number of cultural institutions’ rehabilitation projects. It didn’t earn two-thirds vote required to pass, but Yaroslavsky said it spawned the effort that led to the development of the Valley Performing Arts Center at Cal State Northridge, as well as private fundraising for LACMA, and it accelerated the completion of the Walt Disney Concert Hall.

Broad also spent the past 20 years working to improve the public school systems nationwide after seeing drops in education rankings. His foundations have invested billions of dollars in public education, science and medical research, and efforts to expose the best art in the world. In 2019, Broad wrote an op-ed in The New York Times addressing issues of income inequality, and supporting raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour.

“Eli Broad was a truly great American whose generosity knew no bounds,” said Related Companies Chairman and Founder Stephen Ross in a statement. “What Eli did for education, public health, medical research, and, of course, the arts in this country — and especially in Los Angeles — are his eternal legacy. It’s hard to put into words how much I respected and admired Eli, whether it was across the table in a negotiation or as a partner along Grand Avenue in Los Angeles.”

Broad has said he was most proud of the medical and scientific advancements made via the Broad Institute. About 20 years ago, the billionaire put up $100 million and convinced Harvard and MIT in Cambridge to each contribute the same amount to establish an institute after geneticist Eric Lander helped sequence the human genome. After the first decade, the institute had developed the leading tools for analyzing genome data, and generated more cancer genome data than any other center in the world. To date, the Broad Foundation’s investment in the institute totaled more than $1 billion.

Yaroslavsky said Broad saw himself as a city builder and a civic leader, who invested his wealth for the good of the city, not for his own self-aggrandizement.

“It was about more than his own bottom line, it was about the communal bottom line,” he said. “We have more than our fair share of billionaires in L.A., but if half of them had the same sense of civic responsibility that he had, there’s no limit to what we could do collectively in Los Angeles.”