After Chewing Up Retail, Amazon Spits Out Its Own Plans for Brick-and-Mortar

By Rey Mashayekhi May 23, 2017 10:30 am

reprints

Twenty years ago this month, Jeff Bezos took Amazon—the online book retailer he started up in his garage in Bellevue, Wash., in 1994—public with an $54 million initial offering on the NASDAQ stock exchange.

The IPO valued Amazon at $438 million. While Bezos would subsequently have to steer the company through investor concerns about its profitability (Amazon wouldn’t turn a quarterly profit until 2001) as well as the dot-com bubble’s eventual collapse, Amazon would persevere.

Today, you can forget about that $438 million valuation; Amazon’s market capitalization is approaching $460 billion, with its growth having accelerated in recent years thanks to its dominance in the increasingly influential e-commerce sphere it helped revolutionize. The company has long since outgrown the label of online bookseller, with loyal customers turning to Amazon for everything from electronics and appliances to clothing and furniture.

Along the way, Amazon—which accounted for a remarkable 43 percent of all online sales in the U.S. in 2016, according to a recent report by e-commerce data firm Slice Intelligence—has helped bring about an existential crisis of sorts in the traditional, brick-and-mortar retail sector.

As consumers have drifted toward the convenience of online shopping, retail chains dealing in products from shoes, like Payless, to electronics, like RadioShack, have drifted into bankruptcy. Department stores like Macy’s and J.C. Penney and big-box retailers like Sears and Kmart (both owned by Sears Holdings) have been forced to shutter hundreds of stores across the country, and even higher-end brands like Polo Ralph Lauren—which announced in April that it would close its flagship Fifth Avenue location, despite still being on the hook for $70,000 per day in rent—have vacated prime brick-and-mortar real estate.

By early April, nearly 2,900 physical retail store closings had been announced across the U.S. in 2017, according to Credit Suisse, with closings on pace to exceed 8,600 over the course of the entire year—a number well above the 6,200 locations that were shuttered in 2008, during the height of the Great Recession.

It is a trend that has forced retailers to adapt or die. Last month, it was reported that Wal-Mart was in talks to acquire online men’s apparel retailer Bonobos for around $300 million. That would follow similar recent ventures into the e-commerce space by Wal-Mart, which last year acquired Jet.com for $3.3 billion and picked up outdoor apparel website Moosejaw for $51 million in February.

The irony, then, is that just as Amazon’s business model has forced about a recalibration of the entire retail industry, so has Bezos’ company sought to venture into the brick-and-mortar space itself via an ambitious, multi-pronged approach to physical retail locations.

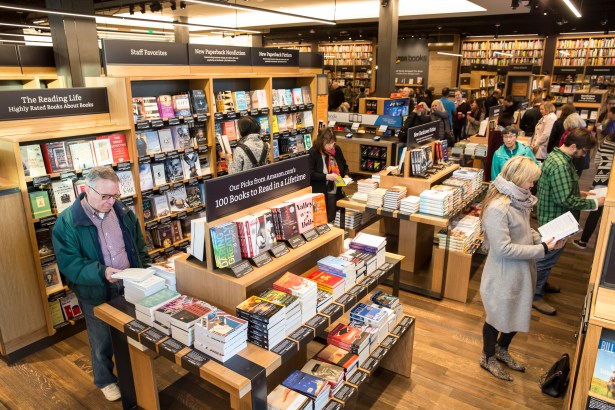

Since opening its first bookstore in Seattle in 2015, Amazon has opened an additional five stores in markets including Portland, San Diego, Chicago and the suburbs of Boston—venturing into a market that it helped annihilate, putting bookstores like Borders out of business in the process. The company has announced plans for another six stores across the country, including two in New York: one at Related Companies’ Shops at Columbus Circle in Midtown and another at Vornado Realty Trust’s 7 West 34th Street, across from the Empire State Building.

In addition, it emerged last year that Amazon plans to significantly expand its pop-up retail presence at malls and other shopping locations across the country, with as many as 100 kiosks and small-footprint spaces expected to be open by the end of this year (Amazon had only around 16 such popups open as of last summer). The stores allow the company to directly peddle its electronic products, like the Kindle e-reader and the voice-interactive Echo “smart speaker,” to consumers.

Meanwhile, in Seattle, Amazon continues to pilot its Amazon Go convenience store concept, a grab-and-go store using sensor technology allowing customers to buy snacks, beverages and other goods without having to go through checkout lines. And 10 years after launching AmazonFresh, its grocery delivery service now active in around 20 markets in the U.S. and Europe, Amazon has sought to further grow the platform via AmazonFresh Pickup, which is being piloted at two locations in Seattle and seeks to cut delivery costs in the already low-margin grocery business by enabling customers to pick up their orders on-demand.

Most of these physical retail initiatives have launched or been announced over the course of the last year, and they signal a tangible shift toward brick-and-mortar operations that promise to further grow Amazon’s influence in the current retail climate. However, they still represent a mere fraction of the company’s overall business, and questions remain over their effectiveness as a business strategy.

“I think there’s a wait-and-see approach; on the surface, it does seem counterintuitive to how they’ve built up their business, which is bypassing stores and getting a wide selection of products delivered to [the customer’s] door,” R.J. Hottovy, a Morningstar analyst covering the retail, restaurant and ecommerce sectors, said of Amazon’s brick-and-mortar initiatives.

Hottovy added, however, that many facets of the company’s physical retail operations are “complementary” to Amazon’s business model. The bookstores, for instance, are perceived as a way to drive Amazon Prime memberships, Hottovy said, since Prime members get reduced prices on the books and products available. Like the pop-up stores, the bookstores also create another platform for Amazon to spotlight and sell its electronics products directly to consumers.

Amazon has also sought to bring the hallmarks of its online experience—convenience and personalization—to its brick-and-mortar offerings, further separating itself from traditional retailers whose business model it has torn up.

“I’ve been asked for 20 years, ‘Will you guys ever open physical stores?’ ” Bezos told Fast Company last year. “And I’ve answered pretty much the same way the whole time, which is that we will if we have a differentiated idea…It can’t be a ‘me too’ offering, because the physical world is so well-served already.”

Barbara Kahn, the director of the Jay H. Baker Retailing Center at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, told Commercial Observer that she had recently visited both Amazon’s bookstore in Seattle and its Amazon Go pilot location and was struck by the extent to which the company seeks to deploy technology to provide a personalized, “frictionless” consumer experience.

“From a retail point of view, the merchandizing isn’t what’s driving it,” Kahn said. She noted how prices are not listed on the books sold at Amazon’s bookstores; rather, customers are able to scan the books (which face cover outward on the shelves, rather than spine out as in most traditional bookstores) with an Amazon app on their phones to receive information on the product.

“You not only get information about the book but also the price they’re going to charge you,” she said. “And they get all sorts of information that they can use.” Kahn speculated that Amazon would be able to use this data—the specific titles, authors and genres that customers browse through—to “calibrate what price they’re going to charge you” for specific items. (An Amazon spokesman disputed Kahn’s speculation, telling CO in a statement: “We offer the same great low prices on all products to all our customers.” Amazon declined further comment for this article.)

Hottovy echoed that Amazon’s wealth of customer information and ability to predict consumer preferences is part of the “end game” of every aspect of its retail operations—and one that will continue to give it an advantage on the traditional brick-and-mortar retail sector for years to come. “That [data] is going to be something nobody else has access to,” he said. “That’s clearly part of the design of the bookstores.”

Amazon Go, meanwhile, remains in the pilot stage at its solitary location in Seattle, despite plans to open the store to the public this year and expand via locations in other markets. That delay has been a consequence of technical issues related to the store’s sensor technology—which is supposed to automatically detect the items customers pick up off the shelves, allowing them to leave the store without having to go through a checkout process. (In March, The Wall Street Journal reported that the technology was experiencing difficulties when more than 20 people were in the store.)

Of course, Amazon is far from the only online retailer to have expanded into the physical world in recent years with the likes of Bonobos and eyeglasses designer Warby Parker, to name only a few, among the companies that have parlayed their e-commerce success into brick-and-mortar locations. Many of those brands have already seen the strategy pay off—and in perhaps unexpected ways.

“When I’ve talked to other clicks-to-bricks retailers, almost all of them have told me the same thing—that when they open a store in an area, their actual e-commerce [sales] in the same area shoots up 15 to 20 percent,” Garrick Brown, Cushman & Wakefield’s director of retail research for the Americas, told CO. “The physical store becomes the embassy of their brand.”

Physical locations also assist online retailers with an easier, more cost-effective way of dealing with merchandise returns and shipping those returns in bulk—a method that Amazon, with its business-wide emphasis on customer service at the expense of margin, is anticipated to deploy at its own locations in the coming years.

Brown noted that Amazon is entering the brick-and-mortar space at an opportune time from a real estate perspective, with the company able to capitalize on the rising vacancies and declining taking rents that its success has helped bring upon the market.

“They would get great real estate deals right now, especially with all the [store] closures,” he said. “Now suddenly, we have contraction from a lot of apparel [retailers] and markets where restaurants are struggling to make it. Vacancy is ticking up, and on a cyclical basis if you’re going to make a move, now is the time to make deals.”

Thus far, Amazon has shown a desire to open locations in high-traffic locations in close proximity to transit hubs and a relatively affluent customer base. James Famularo, a principal and senior director of retail leasing at Eastern Consolidated, noted that Amazon’s two announced New York bookstores to date, at Columbus Circle and West 34th Street, take advantage of heavy tourist and commuter traffic, respectively.

Famularo said that he and his team at Eastern have shown several retail locations around New York to Amazon on behalf of their own clients, and he echoed the widely acknowledged sentiment of the company as “tight-lipped” operators who are reluctant to give away any indication of their next move.

“You’ve got to give it to them: They’re aggressive,” he said, noting that retail landlords are largely more than receptive to whatever concepts Amazon may throw their way. “Nowadays, with the uneasiness of Ralph Lauren turning in the keys [at 711 Fifth Avenue], I think people are testing out different markets. And landlords won’t say no to the money.”’

AmazonFresh has had a slightly rockier road to market share. Amazon has had to grapple with logistical and economic challenges associated with grocery delivery—notably the “last mile,” as the transportation of goods from a local hub to the actual consumer is known in supply chain jargon—as well as customer reluctance associated with the psychology of buying food without seeing it first.

Cushman & Wakefield’s Brown noted that, while Amazon’s ambitious expansion of its fulfillment centers in recent years means that there’s now an Amazon warehouse “on the outskirt of every major metro area in America,” that infrastructure doesn’t necessarily offer itself to AmazonFresh.

“These [warehouses] are 40, 50 miles outside of city limits; you can’t deliver groceries from there,” he said. “You’re looking at your [food] distribution hub being within a one- to two-mile radius, at most.” (Brown did cite the view that Bezos’ 2013 acquisition of the The Washington Post was at least partially motivated by the major daily newspaper’s expansive distribution network. “When they rolled out AmazonFresh in the Baltimore market [in 2015], they used The Washington Post distribution chain that was already in place [to deliver],” he said. “He did not just buy a newspaper; he bought trucks.”)

AmazonFresh Pickup, which was announced in March, is one way the company is seeking to work around that challenge.

“What [Amazon wants] to do to be efficient is to have the consumer take control of that last mile,” Kahn said. “If you can make it convenient for the customer to pick up the groceries, then they’re handling the last mile.”

There is also the possibility that, rather than looking at hard-to-find industrial properties in urban centers that it could use as food distribution hubs, Amazon instead looks at smaller retail locations—similar to Amazon Go—as a means of addressing the obstacles associated with the AmazonFresh delivery model.

“When I look at that [Amazon Go] convenience store they opened in Seattle, I ask myself, ‘Does Jeff Bezos want to sell slurpees?’ ” Brown said. “Instead of looking for an 80,000-square-foot warehouse that does not exist in the urban core, what’s readily available? There’s plenty of small retail space.

“This could be the way that they really ramp up the growth of AmazonFresh,” he added. “I’m not surprised if we’re seeing hundreds of these Amazon food and convenience stores popping up. Of course, they’ll have the benefit of being brick-and-mortar [stores], but the real goal would be to boost their delivery of AmazonFresh.”

Whatever direction Amazon ends up going in with its real estate, virtually no one expects that Bezos’ appetite for expansion is sated. In March, The New York Times reported that Amazon is exploring the idea of “showcase” stores specializing in furniture, appliances and other home merchandise that customers are usually reluctant to buy online without seeing in person first.

The Times also reported that Amazon has been working on a venture, known internally as “Project Everest,” that would see it open brick-and-mortar grocery stores in India—a massive, underserved market. And just this month, it was reported that Amazon is getting increasingly serious about long-gestating plans to get into the pharmacy market and compete with the likes of CVS, Rite Aid and Walgreens.

“It’s at the point where it’s clear, based on the number of closings in the retail space just this year, that Amazon is in a good position,” Hottovy said of Amazon’s physical retail operations. “Now is the time to take it to the next step. If done right, it’s a way to make it an extension of the online platform.”

After a wildly successful first two decades as a public company, no one is certain what the next two decades will bring for Amazon. But should it become the world’s first trillion-dollar company—as some have suggested is Bezos’ goal—it would likely be in no small part due to the fact that it pivoted at a critical moment and conquered both internet and brick-and-mortar retail simultaneously.

Update: This story has been updated to include a statement from Amazon.