The Need for Feed: The Next Wave of Food Halls Reaches SI and the Bronx

By Lauren Elkies Schram September 28, 2016 10:30 am

reprints

Has New York finally achieved food hall saturation?

Think about it: In 2010, when Eataly opened in the Flatiron District, it was a phenomenon. It was an Italian market, a rooftop bar, a counter for a casual pizza, a place to have a gourmet dinner and a gelato bar for dessert—all under the same roof. There wasn’t much else like it in New York.

But in 2016 one Eataly is not enough for Gotham. A second Eataly opened in August at 4 World Trade Center.

Isn’t this overkill?

Apparently not. Since it’s been open, it’s attracted throngs of New Yorkers and out-of-towners, all eager to sit down with a board of salumi and a glass of wine, overlooking the World Trade Center memorial.

If you think the food hall phenomenon has peaked, you’re insane. If anything, the appetite for permanent artisan and chef-driven food halls appears insatiable as more and more iterations crop up in the city, even in areas once considered culinary wastelands.

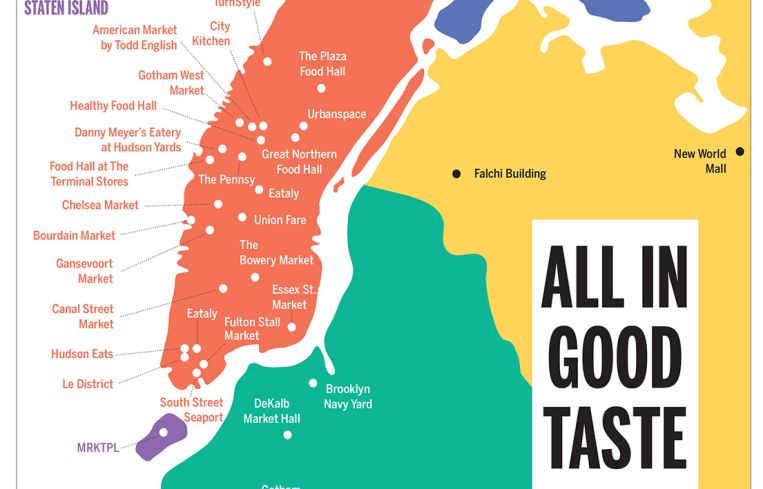

Today, there are at least 30 food halls operating or in the planning stages throughout the city, according to information compiled by Commercial Observer.

“This is a really popular space right now,” said Steve Zagor, the dean of the School of Business & Management Studies at the Institute of Culinary Education who is assessing food hall conditions in New York City for a consulting client. “It really fits the way we are now.”

In Manhattan’s South Street Seaport, chef and restaurateur Jean-Georges Vongerichten will be opening a 40,000-square-foot food hall in the Tin Building along with developer Howard Hughes Corporation next year. It “will be inspired by the original Fulton Fish Market,” according to a press release.

Even the outer-boroughs have gotten in on the act. Next year, the 35,000-square-foot DeKalb Market Hall will be opening in Downtown Brooklyn along with the rest of the City Point complex and the city-owned Brooklyn Navy Yard Building 77 will feature a 60,000-square-foot ground-floor food hall and manufacturing plant, anchored by the first Brooklyn outpost of Lower East Side store Russ & Daughters.

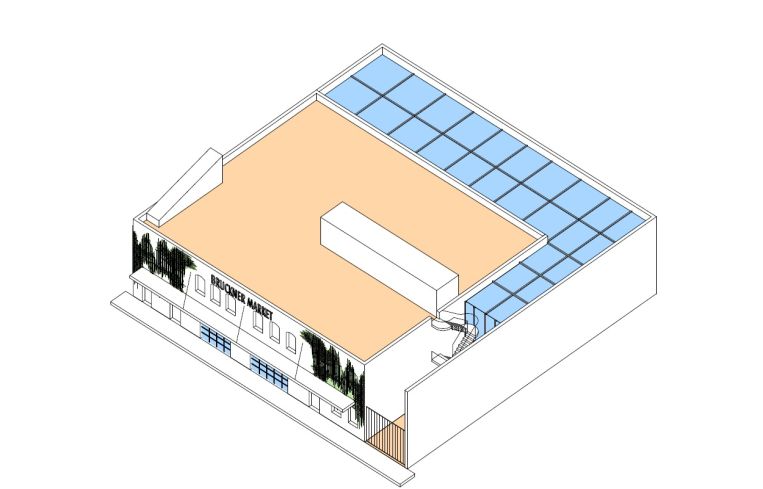

But Brooklyn is almost to be expected to go along with this kind of phenomenon (especially when you consider that food venues like Smorgasburg took root in Brooklyn.) What’s more surprising is that Staten Island will see a 12,415-square-foot food hall called Marketplace at Empire Outlets (MRKTPL) in November 2017. A year later, the South Bronx will become home to Bruckner Market in 16,000 square feet at 9 Bruckner Boulevard.

For New Yorkers and tourists, food halls provide ample, and often interesting, choices under one roof. For vendors, they provide a lower bar for entry (maybe $45,000 in a food court versus $1.2 million to $2 million to open a restaurant) and less risk. For landlords, they “serve the office tenants [and] add value to the office square footage,” said Chase Welles, a partner in SCG Retail. He recently brokered a food hall deal for Kushner Companies at the old New York Times Building at 229 West 43rd Street. (Outstanding Hospitality Management Group signed an 11,970-square-foot lease at Kushner Companies’ retail condominium at the building between Seventh and Eighth Avenues for a curated food hall by celebrity chef Todd English. Kushner Companies’ chief executive officer is Jared Kushner, who is also the publisher of CO.)

Not all food halls are created equal and not all are bound to succeed. Jeffrey Chodorow’s 15,000-square-foot futuristic food hall FoodParc (with touch-screen ordering) opened in the Eventi Hotel in Chelsea in October 2010 and closed under new management a couple of years later. The decor included a large movie screen in the courtyard, visible while eating indoors. One New York Times review said of the food, “Too bad most of the food at FoodParc is so disappointing.”

What might be most surprising is that so many of the chain fast-food restaurants, which would have dominated this kind of venue 20 or 30 years ago, haven’t had any place at all in them today (unless you count Shake Shack). The trend is toward fancy chefs and unique ventures.

“I think the cheesy food hall movement has peaked,” said Anna Castellani, the managing partner of the upcoming DeKalb Market Hall. “The good ones will survive. The ones that aren’t curated will not.”

Location is critical when it comes to a restaurant, and the same holds true for a food hall.

The 8,000-square-foot food hall The Pennsy, at 2 Penn Plaza above Penn Station, is benefiting from its close proximity to Madison Square Garden (and the fact that the surrounding area is a culinary desert).

Mary Giuliani of Giuliani Social, who curated and operates The Pennsy, said the five-concept hall has been performing well since opening at the beginning of the year.

“We see in The Pennsy that people are very excited about trying food that is served quickly and has a lot of thought put into it,” Giuliani said.

One of the vendors at The Pennsy who spoke on the condition of anonymity said there is a big drop off in traffic on the weekends, unless there is a big event at the Garden.

Establishing a counter in The Pennsy made sense from an exposure standpoint, he said, with the “millions [that] go through Penn Station on a daily basis [and the] tremendous foot traffic to the Garden.”

Butcher Pat LaFrieda, the chief executive officer of Pat LaFrieda Meat Purveyors, opened his first brick-and-mortar location in The Pennsy.

“I opened in The Pennsy because I was dared to help change the quality of food in the immediate area of the Garden by Vornado Realty [Trust],” LaFrieda said. “In touring the area, it quickly came to my attention there were little quality food options and the opportunity to be part of the revolution was too great to pass. Vornado gave us an amazing deal and the ability to offer our product directly to consumers for the first time.”

Operators cannot assume that just because they build a food hall, people will come. Beyond interesting and tasty food options like ramen burgers, Cambodian-inspired sandwiches and shrimp and pineapple ceviche, the area needs to have the density to support a food hall.

It boils down to “location, location, location,” said Vin McCann, a partner at restaurant consulting and development company Heyer Performance, which conceived of the Great Northern Food Hall, which opened this summer in 6,000 square feet at Grand Central Terminal. “When you build a food hall, for the most part, you add five or eight restaurants, but you haven’t added any population, right? You’ve got to steal customers from another place. If they’re not there to steal, you fail.”

Location works in a number of ways. Take Gotham West Market. In October 2013, Gotham Organization opened Gotham West Market, an upscale food court at 600 11th Avenue between West 44th and West 45th Streets, where the developer got noodle slinger Ivan Orkin and “Next Iron Chef” Seamus Mullen to open up stalls. The location was very far west, which was a notable drawback. But it also had a great built-in advantage: over 1,000 apartments above the food court. The remoteness of the building probably works for and against Gotham Organization. There are no doubt residents who don’t want to trek far for supper, but more than one real estate observer CO spoke to expressed wariness about how well Gotham West market does with little density beyond the residents upstairs.

Gotham Organization is now preparing for the opening of the 16,000-square-foot Gotham Market at The Ashland in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, at the end of the year.

“The market has been a hit,” said Chris Jaskiewicz, the president of Gotham Properties and Hospitality, owner of Gotham West Market and Gotham Market at The Ashland. “In a lot of ways it’s started a culinary trend. A lot of developers, I don’t want to say copied it, but they’ve mirrored it in their developments nationally and internationally.”

One way in which the usual location rules might differ from what one would expect is in the case of Gansevoort Market. Earlier this year, the market moved from 52 Gansevoort Street to 353 West 14th Street—which a source said is not as good an address because even though it is closer to the subway, locals are rushing to hop on and off the train. In the previous location, west of Ninth Avenue, people tended to stroll by and stop in.

“I don’t see that market being half as successful as the old market because of its location,” said the source.

When done right, a food hall can be part of the renaissance of a neighborhood, or even a borough.

There will be north of 40 concepts going into Marketplace at Empire Outlets (MRKTPL), inside BFC Partners’ Empire Outlets retail complex in the St. George area of Staten Island. And the developers believe this upscale food court will be a boon to the borough.

“On Staten Island, our food choices are slim to none,” said Joseph Ferrara, a principal of BFC, noting that MRKTPL will act as the project’s “food and beverage anchor.”

MRKTPL’s 10-year $125-per-square-foot triple-net lease includes 12,415 square feet inside and access to a 2,000-square-foot private rooftop, Ferrara said.

“Obviously, we’re going to have food, but we’re going to have mixed retail in there and be more of a traditional marketplace,” said Manny Del Castillo, a co-founder of MRKTPL, as well as the creative director behind the first Gansevoort Market.

In Manhattan, there will be a 12,000-square-foot Canal Street Market at 261-267 Canal Street between Broadway and Lafayette Street. The retail portion will launch on Oct. 13 with more than 27 artists and artisans and on Nov. 1, more than 11 food and drink vendors will sell their goodies.

“The general feedback I’ve heard from people who live and/or work in the immediate area is that there is a lack of quick and approachable food options,” said real estate developer Philip Chong of HCRE, who owns the Canal Street buildings and will operate the street market. “While we were exploring ideas of tenants, we explored the idea of a multitenant format. We saw it exploding in other areas of the city so we decided to pull the trigger ourselves.”

In Downtown Brooklyn, Castellani said, “We’re really creating a food environment in a neighborhood that doesn’t have any food.”

And in the Bronx, Keith Rubenstein of Somerset Partners is hopeful that Bruckner Market will be a big hit for the residents in the 2,000 homes he is building across the street as well as other members of the community.

“I thought one site with multiple venues would be a great opportunity since nothing like that existed in this particular area,” Rubenstein said. And he believes if the counter options are “quality,” people will view Bruckner Market as a destination rather than a place just for locals.

Also in the Bronx, Eater reported that Italy’s chef Massimo Bottura and actor Robert De Niro may be cooking up plans for a food hall. A spokesman for De Niro didn’t respond to a request for comment.

But, as one might expect, Manhattan is still dominating the outer-boroughs in terms of future food halls. On Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Taconic Investment Partners, L&M Development Partners and BFC Partners’ Essex Crossing development will become home to the new Essex Street Market (the original opened in that neighborhood in 1940). There’s a food hall coming to The Terminal Stores warehouse complex at 271 11th Avenue at West 28th Street. Long in the works is a deal for celebrity chef-cum-travel reporter Anthony Bourdain to open a 100,000-plus-square-foot international food hall at Pier 57 at West 16th Street and the Hudson River, and restaurateur Danny Meyer may be opening a 40,000-square-foot food hall at Hudson Yards (Per Se and French Laundry’s Thomas Keller is also planning a restaurant at the development).

In addition, James Famularo, a senior director in the retail leasing division of Eastern Consolidated, said he and colleague Ravi Idnani just negotiated a 15-year deal for “the city’s first healthy food hall” at 221 West 37th Street. The tenant, who is behind vegetarian restaurant Clean Table (at 28 Seventh Avenue South), leased 3,000 square feet at grade and 3,000 square feet below ground.

Food halls are “a longer-term trend,” said McCann. “Landlords have discovered that food is something serious. People like it and they like it convenient.” He added, “It works for the operator because you have critical mass. It works for the consumer because it’s super convenient.”

And while the food hall business can be profitable for vendors, chefs have to be able to play well with others.

Philippe G. Massoud, the chief executive officer and executive chef at full-service restaurant Ilili, Ilili Box food stand in the Flatiron pedestrian plaza and Ilili Box in City Kitchen, said business at the food hall “has been steady more or less since it opened.”

But he would not establish an eatery in another food hall because “ultimately you want to control your experience with your customers and want to give your customer the best experience. With the food hall experience you don’t connect. And there are many factors that are outside of your grasp—the seating, the sound, all the intangibles, everything that makes it the full experience.”

Meanwhile, the proliferation of food markets continues unabated.

Shane Davis, the head of strategy and development at Hospitality House, said he is currently conceptualizing, creating business plans for and leasing up food halls for developers within a Manhattan luxury department store, an airport terminal in Queens and a creative office repositioning in Brooklyn. He was unable to provide further details on the projects.

Does this portend any danger? Will there be a final tipping point when the market really does become oversaturated?

“There can be too many of them. I mean, how many lunches do you have a day?” said Jeffrey Roseman, an executive vice president and a principal at Newmark Grubb Knight Frank.

The main challenge food halls face, Zagor said, is “the day parts are really limited. It’s more of a lunch/breakfast concept. They have limited traction in evenings and on weekends.”

To cut it in the future, Michael Goldban, the senior vice president of retail leasing at Brookfield Property Partners, said food halls will have to start experimenting with more evening hours, providing entertainment and serving beer and wine. To that end, Brookfield is going to start hosting events in Hudson Eats, its 28,610-square-foot food hall in Brookfield Place.

Once a food hall is up and running, it takes time to establish its market share.

The response has been positive to the opening of the 42,000-square-foot Eataly at Westfield World Trade Center, according to Fabrizio Germano, the general manager of the Italian market.

“We are definitely trying to find our space,” Germano said. “It’s not so easy to get the locals here, but we’re improving day by day.”

David Haisley, the general manager of Urbanspace Vanderbilt, said initially his Grand Central Terminal-area market was viewed as solely a lunch spot, but it has been grown into a place for breakfast, happy hour and even weekend brunch.

“We see a lot of potential at night,” Haisley said.

No one whom CO asked would hazard a guess at the length of the food hall trend or how many years we are into it.

But Goldban said, “Big picture, we’re still in the early innings of this trend and for good reason because it’s a great social experience. I think that it’s not for every street corner. For the right projects and the right operators I think it has a lot of legs.”