How the World Trade Center Staged a Comeback After the Most Devastating Attack in History

By Terence Cullen September 9, 2016 9:00 am

reprints

Fifteen years ago this week, two airplanes struck the Twin Towers, which killed more than 2,600 people. (The number gets closer to 3,000 if you factor in two simultaneous attacks in Pennsylvania and Arlington, Va.) The assaults set off a series of world events that led to war, seismic political change and hundreds of other things (small and large) that have been incorporated into our modern life.

But the aftermath is as much a real estate story as it is one of security, elections or culture. The loss of the two towers, and thousands of innocent lives changed how buildings are constructed in New York City and how landlords have to protect workers. The hulking 1 World Trade Center, completed in 2014, was sent back to the drawing board at one point to ensure the base of the building could resist any future copycat strike.

Elected officials, victims’ families, civic groups and developers squabbled for about a decade about what to do with the 16-acre site and who would rule the land. Developer Larry Silverstein spent years in court wrangling insurance money in the wake of the attacks, which would help finance the reconstruction.

Despite the very public back-and-forth, reconstruction of the World Trade Center site is nearing its zenith; in total, three out of four planned towers at the site are either finished or en route to completion (not to mention 7 World Trade Center, which is across the street and was finished a decade ago). The long-delayed World Trade Center PATH station opened earlier this year, as did the shopping concourse below the streets. All that’s left on the drawing board is a performing arts center and 2 World Trade Center, for which the developer is still in search of an anchor tenant.

To commemorate the event that changed New York City and the country forever, we took a look at some of the key years and milestones since that fateful day.

A Silverstein Properties-led venture signed a 99-year ground lease in July to take over the World Trade Center for $3.2 billion.

On Sept. 11, a plane struck the North Tower, followed by a second hitting the South Tower as part of a coordinated terrorist attack on the United States. Both buildings, known as the Twin Towers, collapsed soon after, along with the fully evacuated 7 WTC.

In total, 2,606 people died in New York City that day, nearly 500 of whom were uniformed first responders. The entire 10-million-square-foot World Trade Center complex was destroyed by the attacks.

As a result, the real estate community worked together to find tenants temporary space usually free of charge, as well as make sure that Downtown was open for business.

“We kept saying let’s just get it open again so that people know that Lower Manhattan is going to work,” said Steven Spinola, the then-president of the Real Estate Board of New York. “That meant that we didn’t expect that anybody [in the industry] would be taking advantage of the terrible disaster that took place. Brokers stepped up and tried to help tenants find space.”

Larry Silverstein broke ground in May to build 7 WTC on part of the original building’s footprint. Despite criticism that he was building too soon, Silverstein declined to delay on that particular tower because the original was home to a Consolidated Edison station that powered Lower Manhattan.

“[Silverstein] already knew from both Con Ed and the public authorities that there was a need to get 7 WTC going very quickly because of the electrical power substation in the base of the building, which had been destroyed,” said John “Janno” Lieber, the head of World Trade Center development for the developer. “We believe that, in a positive way, this project pioneered core attributes and values that ultimately did inspire a lot of the good stuff that has taken place on the rest of the site.”

At a December presentation at the Winter Garden (now part of Brookfield Place) across the street from Ground Zero, Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind unveiled what would become the winning bid for the project. The plan called for a memorial, a museum, a reintroduction of Fulton and Greenwich Streets and a series of buildings whose centerpiece would be a 1,776-foot tower. Although Silverstein Properties executives had hired David Childs of SOM to design its properties, the company embraced the master plan. (Gov. George Pataki would later name the tallest building—1 WTC—the “Freedom Tower,” a name that received mixed responses and was later abandoned.)

In May, Silverstein Properties opens the 1.7-million-square-foot 7 WTC with asking rents averaging $55 per square foot, despite charges by the city that the rents were too high to lure tenants back to Lower Manhattan. By that point, the developer was the sole occupant, but leases were signed with Ameriprise and the nonprofit New York Academy of Science.

After years of fighting between the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey and Silverstein Properties, the two sides came to a new agreement on who would control which parts of the 16-acre site. Silverstein Properties handed over the rights to develop the Freedom Tower to the Port Authority, along with insurance money from the attacks.

The developer would have the right to develop three office towers between Church and Greenwich Streets (which became 2, 3 and 4 WTC). Silverstein Properties was given a timeline to develop a plan for the three buildings, recruiting Fuhimiko Maki, Sir Richard Rogers and Lord Norman Foster to design them. New renderings were released in early September, just days before the fifth anniversary of the attacks.

“We were thrilled because now, for the first time, there was a schedule,” Lieber said. “We set up a design studio on the 10th floor [of 7 WTC], which was much larger than it is now. We basically said everybody has to come in and design there.”

The Port Authority, grappling with construction of the Freedom Tower, declared in January it was looking for a managing partner to build and lease the planned 3-million-square-foot tower.

After another battle between Silverstein Properties and the Port Authority, the two sides reached a new agreement on the terms of the ground rent for the site. Silverstein got a rent reduction for the under-development properties—slated to increase once the buildings were finished and leased—in exchange for federal tax-exempt Liberty Bonds to help finance the project.

Media colossus Condé Nast, the publisher of The New Yorker and Vanity Fair, agreed in May that it would move to 1 WTC. Condé Nast ended up signing a 1.2-million-square-foot lease to occupy the base of the building, leaving behind 4 Times Square in Midtown. (By this point, 7 WTC was almost fully occupied.)

The Durst Organization in June officially became the Port Authority’s equity partner for the building, taking over the tower’s completion and leasing. Durst, which owns 4 Times Square, wound up paying $100 million for an ownership stake in the skyscraper, which was then being built.

“We are thrilled to be part of 1 World Trade Center,” Durst Chairman Douglas Durst said in a statement via a spokesman. “The Trade Center site is better than we could have imagined.”

That September, just in time for the 10th anniversary of 9/11, the memorial plaza opened first to victims’ families and then to the general public. The long-stalled, often-controversial commemoration featured two draining pools, where the towers once stood, and was lined with the names of the thousands who perished.

Silverstein completed 4 WTC, the 2.3-million-square-foot tower that became the first property to open on the World Trade Center site. The Port Authority and the City of New York, along with several media and financial companies, occupy the property.

Following the installation of the 400-foot spire at the top of 1 WTC, the skyscraper officially became the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere at 1,776-feet. (This fueled some controversy: The Willis Tower in Chicago has six more stories than 1 WTC, but the 408-foot mast on the top of 1 WTC was ruled part of the skyscraper’s height by the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat.)

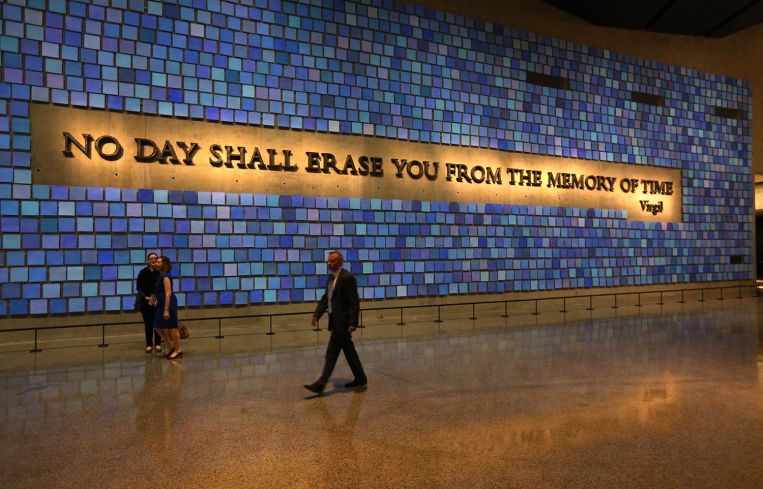

The 9/11 museum opened in May, nearly three years after the memorial was completed. The center’s executives were immediately criticized for hosting a black-tie cocktail party at the site.

In November, Condé Nast began moving its offices to 1 WTC, marking the opening of the tower. It became one of the most prominent media companies to move Downtown.

After months of negotiations, Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. and 21st Century Fox in January backed out of a deal with Silverstein Properties to occupy the yet-to-be-built, Bjarke Ingels-designed 2 WTC. The fate of the building was left in limbo because it did not (and still does not) have an anchor tenant to secure financing.

After 11 years of construction and a $3.9 million price tag, the Santiago Calatrava-designed World Trade Center PATH station opened in March to mixed reactions over the design and cost overruns on construction.

In June, Silverstein topped out 3 WTC. The building is slated to finish in 2018 and will be anchored at the base by advertising company Group M.

“The story of 3 [WTC] to a great extent is that we planned for a financial services tenant in the base,” said Lieber, the Silverstein executive. “And who came and leased that space? Group M—a branding and marketing company. That is hugely symbolic to the change Downtown.”

Later that month, the Port Authority finished the single-acre Liberty Park, a green space atop the complex’s vehicle security center.

The Port Authority commissioners also voted to move Fritz Koenig’s “The Sphere,” a bronze sculpture that survived the 9/11 attacks, to the park—marking the first time the artwork would return to the World Trade Center in nearly 15 years.

Westfield World Trade Center, the 365,000-square-foot shopping concourse that’s part of the transit hub and beneath the buildings, opened in August following its own set of delays, and features a massive Italian market curated by Mario Batali called Eataly (the second in New York).

“This year, the site’s master plan was realized, Westfield opened, the connections between the buildings and transit center have been made and [1] World Trade Center has leased more than 2.1 million square feet,” Durst said in the statement.