Four Iconic Properties That Have Faced Financial Woes

By Danielle Balbi December 2, 2015 1:30 am

reprints

Just before the last downturn, pro forma underwriting in real estate deals was commonplace. While lenders, investors, rating agencies, attorneys and analysts alike swear that everyone is proceeding—or underwriting—with caution today, the market is still feeling the reverberations of the past.

Commercial Observer took a close look at some of the more reputable buildings that have recently faced defaults and tenancy woes, and asked: How can a well-located, iconic building with a high-caliber owner, in a market with rising rents and property values, be sent to the special servicer?

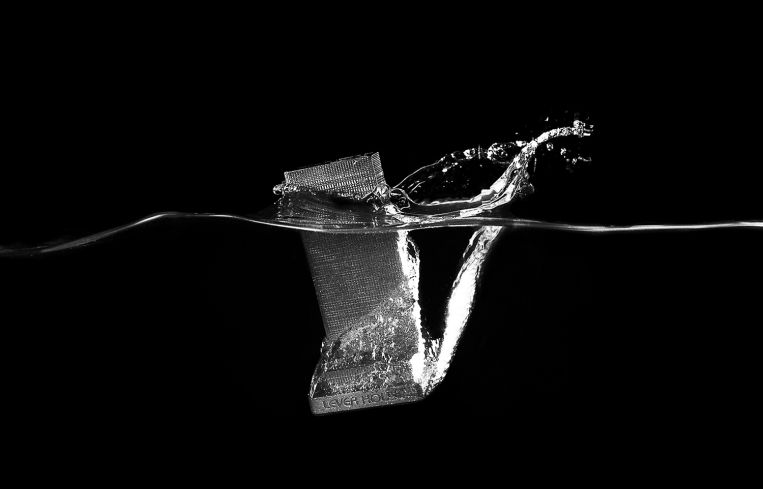

This March, RFR Realty went into maturity default on a remaining $97.1 million in securitized debt on the landmarked Lever House. The company’s co-founders Aby Rosen and Michael Fuchs, along with investor Harry Lis, acquired a long-term leasehold on the 22-story office building at 390 Park Avenue in 1998. The three originally borrowed $110 million, which was securitized in a conduit originated by Credit Suisse First Boston in March 2005, known in the industry as CSFB 2005-C2.

“The building is producing sufficient cash flow to pay debt service right now with a nice margin,” Lea Overby, the head of CMBS research at Nomura told CO in July. “The ratio between the cash flow and debt they have to pay is 1.33—one-third extra than what they need to just service the debt. From that perspective, the building is completely capable of supporting the mortgage in place, so from that point, the property is performing under the terms of the old mortgage—the only issue is this mortgage has matured.”

But the ground lease, though a relatively common feature in buildings across New York, was not well accounted for during the time the mortgage was underwritten. The ground lease on Lever House has a 99-year term—which began on Jan. 1, 1999—which comprises a 51-year term with four 12-year extension options. The ground lease offers fixed rent through 2023, and a fair market value-based reset on the ground rent in 2019.

According to commentary from special servicer CWCapital Asset Management, “The rental reset language in the ground lease is not economically viable and has made a refinance of the loan improbable, given that the anticipated ground rent would increase from $6.15 million annually to an amount in excess of $20 million annually on an asset with consistent historic net operating income of $16 million to $18 million.”

Although it has been nearly nine months since the maturity default, some are more hopeful that RFR will be able to refinance. Lever House’s location in the Plaza District of Manhattan, where office rents are a little pricey, bodes well for the building on the rental front.

The Seagram Building, which RFR also owns, sits just one block south at 375 Park Avenue. The tower is seeing asking rents of $175 per square foot, noted Edward Dittmer, vice president of CMBS at Morningstar Credit Ratings. Similarly, RFR is seeking $160 per square foot in office rent for Lever House, which would mark a noticeable increase from the building’s average rent of $128 per square foot. Mr. Dittmer said that he and his team of analysts underwrote the loan using the $160-per-square-foot rents and didn’t see a loss.

Whether those projections are realistic remains unclear. Data compiled from CBRE places Lever House in the Park Avenue submarket, which is seeing average asking rents of $95.39 per square foot as of Nov. 1, compared to $128.17 per square foot in the Plaza District. Nonetheless, the building remains without a new mortgage.

“It goes back to pro forma underwriting,” Mr. Dittmer said. “A lender today is probably struggling with trying to weigh the fact that this building is capable of generating far greater rents and neighboring buildings are matching those rents. At the same time, it’s tough to go out and underwrite gains in rents that have not yet occurred, certainly from a conduit lender perspective that is a tough loan to underwrite.”

On the other hand, it could be that RFR is hesitant to lock in a long-term loan right now, and would rather wait until preferable deal terms come around, said Dan Flanigan, the chair of real estate and financial services department at the law firm Polsinelli.

Lever House isn’t RFR’s only pricey asset. The company has made headlines over the past year for acquiring many other New York properties, despite rising prices. RFR’s expansive portfolio ranges from dozens of office and retail properties in New York and the Miracle Mile Shops in Las Vegas to hotels in Berlin and Frankfurt. Germany. Earlier this year, the global real estate firm closed a $55 million deal for the old, graffiti-covered Germania Bank building at 190 Bowery. The company is also shedding a few valuable assets, including a 40-story tower in Frankfurt, which sold for $510 million in April.

Borrowers of that profile are, however, unable to move around funds to repay their loans, industry experts explained to CO. “High-profile borrowers have issues because of the use of special purpose entities, which separate assets and in most cases are put together to be a bankruptcy remote,” said William O’Connor, co-leader of the real estate capital markets and CMBS practice group at Thompson & Knight. “As such, it is very difficult with CMBS loans to move assets around to deal with one particular problem loan.”

Even if the real estate firm was to move finances around, it may not solve the problem. Putting equity into the deal could result in more losses for the borrower.

“RFR likely has enough capital to repay this loan in full but in 2023 they are still going to have to deal with the step in rent payment,” Steven Romasko, CMBS research analyst at Nomura Securities, told CO. “If they walk away from it, I’m not sure they would lose a ton of money, but they would certainly be worse off if they repaid the loan and were unable to restructure the ground lease.”

Mr. Romasko noted that when it comes to CMBS as a whole, there is a difference between a borrower’s ability to repay a loan and their willingness to do so.

“Given its non-recourse nature, decisions tend to be much more economical,” he said. “Just because a borrower has the ability to pay off a loan doesn’t mean that they will if the returns aren’t there.”

But the potential damage does not end with RFR. There are investors who have bought into Lever House’s mortgage through the CSFB 2005-C2 deal—and the mortgage accounts for 70.78 percent of the deal’s remaining collateral. Investors on the overall deal are already feeling losses up to the AJ tranche as a result of losses on other loans in the pool. Although the deal’s A4 tranche is paid off, additional losses on the loan could be felt in the AM bond as well, Mr. Romasko added.

“The nature of a non-recourse CMBS loan is such that you can hand the keys back and walk away from it and not have to worry about any kind of recourse,” one special servicer, not involved in Lever House, said on the condition of anonymity.

A spokesman for RFR declined to comment for this story.

Underwriting issues don’t always end in a maturity default, but for a global asset manager like Brookfield Property Partners, it could raise a flag with the special servicer.

Toward the tip of Manhattan, in a market that is experiencing significant office migration from technology and media companies, Brookfield’s One Liberty Plaza in the Financial District was placed on special servicer LNR Partners’ watchlist on Oct. 6, as a result of tenancy turnover.

While industry insiders have noted that a loan’s placement on a servicer’s watchlist is not necessarily indicative of an impending default, vacancy in an institutional building during a booming office market is a telling sign.

Brookfield has a $331 million mortgage on the 54-story tower and the building serves as the largest loan in a Goldman Sachs-sponsored CMBS deal from 2007, known in the industry as GCCFC 2007-GG11, making up 17.9 percent of the pool’s remaining collateral.

“That was certainly originated at top of the market. It is certainly not performing to its original underwriting levels right now, although it is still operating above break-even,” Mr. Dittmer said.

The original loan documents show significant disparities in what the actual incomes and cash flows from the building were, and the growth that was underwritten into them, he explained.

One Liberty Plaza’s net operating income was $59.4 million, compared to an underwritten NOI of $91 million. The underwritten net cash flow was $86.6 million, compared to the underwritten in-place cash flow of $68.3 million, according to the original loan documents.

“Oftentimes, some underwriting tends to be more optimistic, and not enough credence is given to termination clauses in leases,” said Mr. O’Connor. “Tenants go out and there are certain industries that are more volatile and more vulnerable.”

In May 2014, the Bank of Nova Scotia, which occupied 10.2 percent of the One Liberty Plaza’s rentable area, departed. Goldman Sachs moved out of its space in September 2011, though it paid rent until its lease expired in April 2015, and Quantum Corporation, another tenant that occupies 5,422 square feet, is not renewing its lease. Brookfield currently has 13 office spaces for rent in the building, according to leasing information on the real estate firm’s website.

The global asset management company is not worried, though. The tower is currently 82 percent leased, trending toward 90 percent and has very substantial equity, according to a spokeswoman.

“Old debt with an above-market interest rate distorts the coverage ratio and will be replaced with market debt when it matures in the next year or two,” she added. “Marking the debt to market increases the coverage ratio close to [two times]. This is a non-issue.”

To pile on to the list of iconic urban properties that have come under the eye of the servicer is one of the tallest in the country—the Willis Tower.

Last year, Joseph Chetrit’s Chetrit Group, the former owners of the 110-story building, actually requested that a $340 million mortgage on the landmark be transferred to the special servicer because “stronger than expected leasing has caused a need for significant new capital and discussions with the special servicer are necessary to determine how to best accomplish this.” A spokeswoman for the company declined to comment.

The $340 million mortgage is part of a conduit originated by Lehman Brothers in 2007, LBUBS 2007-C2. The Willis Tower—referred to as the Sears Tower at the time of securitization—is the second largest loan in the pool, and makes up 16.9 percent of the total deal. It is also securitized in three other CMBS deals, with additional debt totaling $161.8 million.

“Originally, a substantial amount of debt on the Willis Tower was issued during the peak of the market and being more an iconic property, but one that simply found itself from a leverage standpoint to be very challenging, it is still something I would believe in many cases supports the idea that this is a property by which quality money would support any type of workout efforts,” said Frank Innaurato, managing director of CMBS at Morningstar.

However, the loan was sent back to its master servicer in February 2015 with no changes or modifications, according to commentary from the special servicer. The following month, it was reported that Blackstone signed a contract to buy the tower for $1.3 billion.

“Large successful organizations don’t become what they are by throwing lots of good money at what could be potentially bad money,” said Mr. Dittmer. “These borrowers may have seen that just continuing to fund debt service without any plan to lease the building up ultimately might have been throwing money away. I can’t speak to their motivations, but the basic idea there was that they didn’t have large amounts of cash to have for tenant improvements. That’s still better than defaulting.”

Perhaps the most well known cautionary tale told in the real estate world is the story of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village. When Tishman Speyer and Blackrock purchased the massive middle-class housing complex for $5.4 billion in 2006, the partnership intended to convert it to luxury condominiums. With prices on the uptick, the new owners took out roughly $3 billion in debt on the property across several mortgages, and cash flow projections were optimistically underwritten.

By 2010, the property was underwater, as Tishman Speyer, one of the largest landlords in the country, had defaulted on all of its CMBS loans backed by the multifamily complex.

Rent projections in the underwriting never panned out when a court ruling mandated that owners that received J-51 tax benefits maintain rent-regulated apartments.

Eventually, lawsuits were filed through the capital stack and special servicer CWCapital took the keys to the property in 2014.

While all these four properties—from Midtown to Downtown, and from Downtown to Chicago—have taken different paths to special servicing, one point of commonality is that they were all securitized shortly before the last downturn.

“You look back and some of the lenders were certainly at fault for giving credit, rating agencies were at fault, and in some cases borrowers were saying give me as much in proceeds as you can, and lenders obliged,” Mr. Dittmer said. Market players felt more comfortable letting generous numbers pass through because of optimism about the economy during the last boom.

In the long-term, these CMBS defaults or near-defaults do not hurt this reputable sponsors, according to industry experts.

“There is reputational risk,” Mr. O’Connor said. “Even for anybody who has a Brookfield-like reputation of being a great operator, real estate is not perfect.”

While no real estate player wants to lose their investment, CMBS loans are non-recourse so a borrower does not have as much to drive them to preserve the asset’s value the way a lender would, he said.

“Because of the way CMBS is structured, with special purpose entities and non-recourse loans, you don’t have a direct effect on most of the owners, operators and developers,” Mr. O’Connor said. “It’s not like balance sheet lending, where a default is going to impact your credit. CMBS default these days does far less to your ability to borrow than it probably should.”

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)