Manhattan’s Dimes Square Appears to Have Some Staying Power

Real estate trends, plus a pair of city policies, provide the Lower Manhattan enclave some investment appeal

By Aaron Short October 20, 2025 7:00 am

reprints

A swath of Lower Manhattan has undergone a dramatic transformation in such a short time that its many denizens ironically have declared it all but dead.

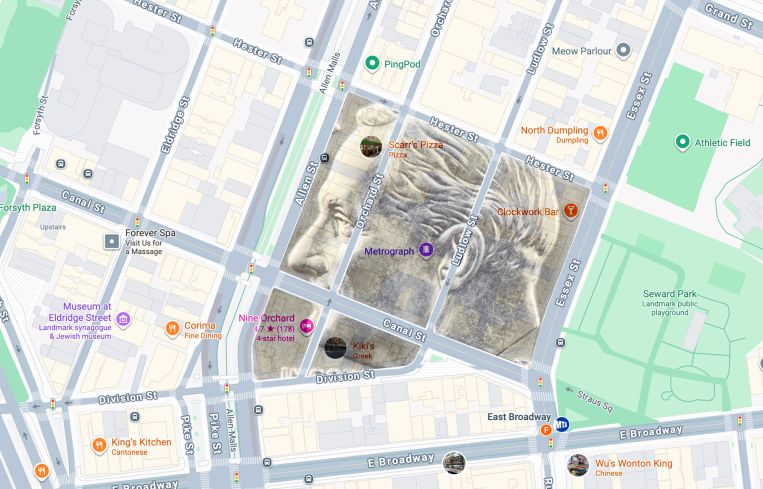

The city’s latest micro-neighborhood-in-the-know has been Dimes Square, a five-block stretch on either side of Canal Street between Allen and Essex streets that is part of the Lower East Side or Chinatown, depending on whom you ask.

Dimes Square isn’t gone, of course, but the transition from appliance stores and takeout dumpling shops to buzzy eateries and four-star hotels has unsettled the neighborhood.

The area once consisted of an eclectic mix of Chinese, Jewish and Latino immigrants who frequented those stores, bodegas and takeout shops that met their needs.

But a much younger crowd swarmed Canal and Division streets to dine al fresco at Clandestino and Kiki’s even before the pandemic. Metrograph, an art cinema with two bars on Ludlow Street, cultivated a devoted following, while several galleries on Henry Street regularly show exhibits from emerging artists.

The changes have not been universally embraced. Longtime residents have complained so incessantly about crowds and late-night revelry that have spilled onto Canal Street on warm nights that they sought to reject one restaurant’s sidewalk cafe application.

Still, commercial real estate investment has poured in. Within the past three years, a luxury hotel with $800-per-night rates, a white tablecloth Italian restaurant called Casino, a chic wine bar named Parcelle, and the $138-per-person Shhh Omakase joint all opened.

The area has also been a nexus for political activity and alt-conservative media, thanks to the opening of Sovereign House on East Broadway. It has hosted magazine launch parties, film screenings and plays. Meanwhile, the Manhattan office of the city’s Democratic Socialists of America chapter, which regularly hosts meet-ups, is a few blocks away on Jefferson Street.

Those who have not visited Canal Street recently could be excused for experiencing whiplash.

“The anchors to really traditional neighborhoods slowed the rate of change slightly, but, like every other neighborhood in New York, change comes fast and furious,” Jordan Barowitz, a principal at Barowitz Advisory, said. “Once a critical mass was hit, it became unrecognizable.”

Media hype has been good for business, but Dimes Square wouldn’t be an attraction without its fashionable bars and restaurants.

“These restaurants are more than places to eat and drink, they’re social hubs,” said Andrew Rigie, executive director of trade group the New York City Hospitality Alliance. “A concentration of these small businesses sparks vibrancy and fuels the social economy by bringing people together, generating jobs and tax revenue.”

The downtown borderland had been referred to as Two Bridges for much of the latter half of the 20th century before it was briefly christened “Chumbo,” or Chinatown Under the Manhattan Bridge, in 2011. The name didn’t stick.

Two years later, restaurateurs Alissa Wagner and Sabrina De Sousa opened Dimes, a SoCal-style cafe offering granola, yogurt and acai bowls that attracted a hip crowd who lingered on Division Street.

Soon, new restaurants joined them and the corridor’s identity began to change. Kiki’s, which featured modernized Greek specialties within what had once been a Chinese printing company, opened in 2015. Scarr’s Pizza, whose owner milled his own dough in the basement, began baking in 2016. And Cervo’s, a seafood-focused Iberian wine bar, debuted on Canal the following year.

People jokingly referred to the area as Dimes Square, and the name caught on. Even the Dimes owners capitalized on its popularity, opening a second outpost, Dimes Deli, in 2015. “We’re just one piece of the whole pun,” De Sousa told Grub Street.

The pandemic only accelerated the revelry. Throngs of social media-savvy Gen Zers flocked to the corridor to partake in its aspirational nightlife and flout social distance mandates.

As the city recovered, a new wave of higher-end restaurants arrived, headlined by Le Dive, a French wine bar that opened next to mainstay Clandestino, and Casino, a coastal Italian hot spot that took over the former Mission Chinese location on East Broadway in 2022.

It helped that rents there are cheaper, often significantly, than other downtown neighborhoods like SoHo, where retail spaces asked an average of $646 to $1,000 per square foot in the third quarter of 2025, depending on the street, according to CBRE. Owners of downtown retail asked on average $245 a foot.

“You can go to Dimes Square, be a pioneer, and have a bigger mark than you can in the East or West Village,” said Chris Coffey, CEO and partner of Tusk Strategies who has advised Le Dive. “If you’re not from New York, you might think you have to be in the West Village.”

One reason many restaurateurs were attracted to Dimes Square is its Parisian sensibilities.

The area caught on as a crossroads where people dined leisurely and socialized throughout the day on the end of Canal Street thanks to the city’s overlapping open streets and outdoor dining programs.

In April 2020, the de Blasio administration launched Open Streets, which at its peak would eventually close 83 miles of roadways to vehicle traffic. Two months later, the city expanded its outdoor dining programs, allowing as many as 12,500 restaurants to set up tables on the sidewalk in front of their establishments and erect covered dining sheds on nearby roads.

Many restaurants profited as a result. In 2021, the average revenue for restaurants in neighborhoods that participated in the Open Streets program was 19 percent higher than the period before the pandemic, while restaurants in areas where streets were not closed to traffic experienced a 29 percent drop from their pre-pandemic average, according to a 2022 city report.

Both programs have been significantly scaled back in recent years, but Dimes Square has largely retained its plaza-like feel, despite the City Council’s rejection of Le Dive’s sidewalk cafe application and new restrictions to Canal’s Open Streets season, as well as reduced operating hours the Canal Street Merchants Association imposed after some neighbors complained.

Still, transportation advocates credit the programs with turning Dimes Square and other swaths of the city into gathering places that saved jobs and boosted New York’s economy.

“We should be doing what we can to return public space to the people of New York,” said Alexa Sledge, spokeswoman for advocacy group Transportation Alternatives. “No matter where you live, you should be able to enjoy your streets and eat a meal outside.”

The Lower East Side has been gentrifying since the 1980s, but Dimes Square may be the last swath of Manhattan to experience the rapid creep of luxury development and displacement.

The neighborhood’s 113-room luxury hotel changed hands three years after it opened, when Austin-based MML Hospitality bought Nine Orchard for $92 million in August. Acclaimed chef April Bloomfield had been in talks to run the hotel’s restaurants.

MML co-founder Larry McGuire told Feed Me’s Emily Sundberg in August, “We were pretty aware of the hotel and the design and the buzz and the culinary and everything,” before the purchase.

More hotel and restaurant deals are likely to continue, cementing Dimes Square as a dining destination. In the next mayoral administration, outdoor dining could flourish as a year-round program while the number of open streets will likely be expanded significantly.

Other commercial investment could be slower, since much of the surrounding area has been built up and there are few vacant lots available for redevelopment.

Change is nothing new for longtime Lower East Side residents. Judy Rapfogel, co-founder and principal of GrandRap Strategies, frequently walks through Dimes Square and marvels at the crowds.

“There are many different versions of cool on the Lower East Side,” she said. “What community have you been to that you’ve lived in for 10 years and said, ‘Oh my, it’s exactly the same’? Things evolve, and you have to grow with that change.”

Moses Gates, an urban planner with the Regional Plan Association, believes Dimes Square’s transformation is part of the larger story about Downtown’s revitalization, and not the flash mobs of celebrities and journalists TikToking their weekend adventures.

“I am a firm believer that development follows the market, it doesn’t drive it,” he said. “Real estate investment isn’t driven by the Dimes Square scene — it’s driven by the fact that Lower Manhattan has a tremendous amount of value, and it has for a very long time.”