San Francisco Office? San Francisco Office.

The market’s comeback story takes shape

By Patrick Sisson December 24, 2024 9:00 am

reprints

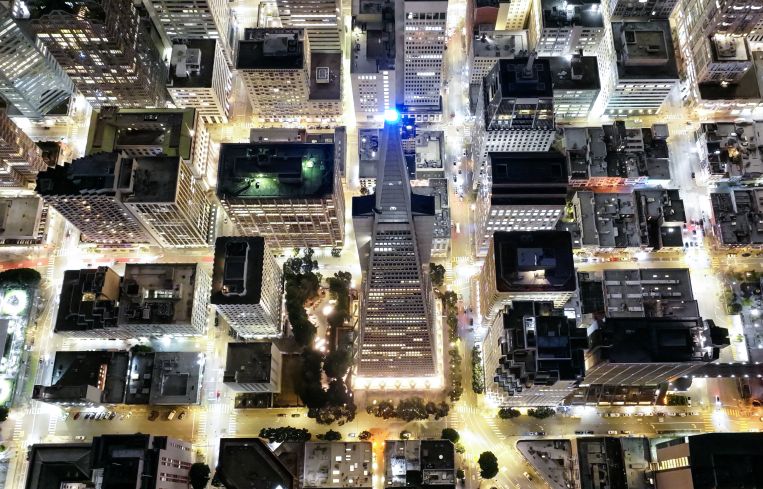

Six months ago, developer Michael Shvo was “struggling to deliver” after sinking nearly $1 billion into the Transamerica Pyramid, perhaps the most visible trophy office in the stumbling San Francisco office property market. A June Wall Street Journal profile chronicling his adventures in high-end commercial real estate noted the half-filled Pyramid had been losing big private equity and insurance tenants amid fraying relationships with Shvo’s development partners as it struggled to swim against the tide in a market with total available space topping 35 percent.

That was then. After reopening the 48-story tower in September to show off a $250 million renovation, Shvo in December could point to 85 percent occupancy and 185,000 square feet in ongoing lease negotiations as signs his long-term bet was the right one.

“All of a sudden, there’s a big boom,” he said about the San Francisco office market. “Couple that with four years of no leasing activity, and that’s what’s happening. Now, I’m obviously very happy about it.”

San Francisco has experienced a vibe shift. It’s a change in mood driven, Shvo said, by a more business-friendly mayor-elect and president-elect and a sense that real estate had finally hit bottom. The office market in San Francisco fell faster than other cities, said Phil Mobley, national director of office analytics at CoStar Group, hitting distressed-level pricing due in part to the public’s perception that the city was infested with crime, drugs and homeless encampments. But the reduced valuations led to a recent spike in leasing activity that he characterizes as “improving, but not healthy.”

Signs of this renewed activity abound, even among a tough overall market. Stabilization is something to celebrate. A much-touted JLL report from November found vacancy had shrunk for the first time in years, shifting a near-imperceptible 34.5 percent to 34.3 percent. Starting rents for 2024 signed leases have been up 4 percent versus 2023, per December VTS data. And with no new office projects set to deliver in 2025, demand may be able to gain on supply.

In terms of market demand and physical office presence, everything is trending in the right direction, said Max Saia, vice president of investment research at VTS. Even the average lease size, which dipped 30 percent to 10,000 per square feet between 2020 and 2022, has now inched back up to 12,000 square feet, a sign of more funding and growth.

A renewed tech industry — long the driving force behind San Francisco’s office leasing — has led the charge. Over the past year, the sector has added 3.1 million square feet of demand and inked big leases, including Open AI’s 315,000-square-foot sublease in September for 550 Terry A. Francois Boulevard, the former Old Navy headquarters.

While the city still has a ways to go — Saia said office leasing activity remains about half of where it was pre-pandemic — the turnaround has momentum. Colin Yasukochi, executive director of CBRE’s Tech Insights Center, predicts 2025 will be the best year for San Francisco’s office market since 2019, with more leasing activity and declining vacancy.

The biggest variable is the city’s downtown area, since businesses there still represent 80 percent of the city’s GDP. While crime and homelessness remain endemic issues, many business leaders believe fortunes have turned on the recent election of business executive and political neophyte Daniel Lurie as mayor. His November victory energized the financial and investment community, many of whom backed him.

The Bay Area’s tech-heavy economy means any shift in this sector ripples through the real estate market. The city’s much steeper downtown downfall, relative to peer cities, exemplifies that. But it also means new trends, and tenants, more rapidly establish themselves here. A quarter of new leasing activity since 2023 has come from artificial intelligence, and VTS data shows that 80 percent of the growing demand for tech office space can be attributed to growing AI firms. Of the city’s 72 AI leases signed this year though early December, 40 were new to market, meaning their first market outside an incubator or coworking space, said JLL research director Alexander Quinn. Last year, there were 35 total.

Tech leases have also grown in size. Firms in the market are seeking about 32,000 square feet on average, and 43,000 square feet among AI companies specifically. Startup Sierra AI, for example, signed a 41,000-square-foot lease in July at 235 Second Street, the same building occupied by Apple.

The surging growth in tech, especially AI and cryptocurrency firms, appear poised to benefit from the incoming Trump administration. That policy support could further energize office leasing. Add in pent-up demand, a return-to-office push from tech giants like Amazon and new hiring next year, and Yasukochi forecasts additional leasing activity.

It’s also important not to overlook the smaller startups that dominate the tech ecosystem, said Cyrus Sanandaji, founder and managing principal of owner Presidio Bay. Venture capitalists and tech accelerators like Y Combinator are pushing for Bay Area-based businesses, he said, and clusters of new companies are locating in Jackson Park, Mission Bay and North Park.

“Most founders and certainly the majority of investors that we talk to today are requiring a full office presence,” he said. “It’s an office-first environment and mindset.”

Tech, and tech-adjacent industries, have also driven a bifurcation in office activity. Professional services firms, from law offices to investment groups, are paying premiums for the right buildings, and “nobody is holding back,” said Sanandaji. Instead, they’re signing 10-year leases to lock down today’s great deals. Firms with the budget and workforce seek trophy offices, while the churning market of startups need bargain spaces to launch new firms.

San Francisco’s vast middle ground of Class B office — too expensive to be a bargain, too cheap to be a luxury — remains troubled. CoStar’s Mobley believes the market will remain fundamentally unbalanced. Much of the extra office space will need to be demolished or converted before there’s significant drops in vacancy. In the meantime, A-plus and trophy office space remains coveted and competitive, much like in New York.

The last few years have also seen significant spending, investment and promotion of the city’s new approach to downtown, one championed in particular by Advance SF, which worked with urbanist Richard Florida to help draft a blueprint for revitalizing the city center. Wade Rose, president of the advocacy group, said the centerpiece of the plan — an effort to give workers, residents and tourists a reason to come downtown in the first place — has begun to bear fruit. A similar mindset can be seen amid the Transamerica Pyramid, which, due to Shvo’s investment, now boasts a revamped park and gathering space.

“We’re definitely seeing the spillover effects of our activities and our success throughout the immediate neighborhood,” said Shvo. Right down the block, his own 545 Sansome Street addition, a 52,000-square foot development, and Related California’s resurrected 412,000-square-foot 530 Sansome are both projected to deliver in 2026. The latter would be the first new commercial high-rise proposed in the city since 2021, a bespoke project aiming to capture trophy office demand.

Rose said that “with the city still in recovery mode,” the election of Lurie is timely, because he understands “what it takes to get us back on our feet.” After he’s sworn into office Jan. 8, Lurie plans to focus on streamlining the city’s bureaucracy and speeding up permitting times for projects. He has also promised to create a downtown development corporation, institute a development tracker, and eliminate red tape to build middle-class housing downtown.

Still, it’ll likely be years before the city’s office market gets anywhere close to its pre-pandemic frenzy. Currently, there’s a significant delta in activity between offices on top floors and bottom floors, and between those located on blocks deemed safe and those that aren’t, said VTS’s Saia. That’s a sharp departure from the late 2010s, when “anybody would take anything.” AI may be ascendent, but as Mobley points out, new leases are far from sufficient to backfill even a meaningful fraction of the space that’s been left vacant.

A third of the city’s office leases are set to expire by the end of 2025, too, potentially introducing a troubling amount of newly available space. And difficult budget decisions may end up overtaking Lurie’s reform efforts; transfer tax revenue has fallen off a cliff, and the city’s projected 2025-2026 deficit is $867 million. But the sense that, instead of spiraling into an urban doom loop, the city’s office market has a long, tough road ahead counts as optimism.

“The institutional landlords who have maintained their conviction in this market, because they’ve been in a long time, they can see the path out,” said Saia. “Those who stuck to their guns, were able to justify the reinvestment internally, are actually in a really good position to start capturing all of this demand.”