The Plan: 55 Broad Embraces Its New Life as a Residential Tower

By Anna Staropoli October 31, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

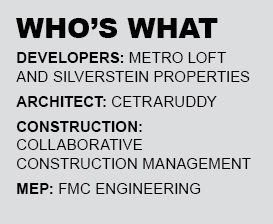

Just last year, 55 Broad Street in Manhattan’s Financial District housed a range of office tenants. Now, residential tenants can lease living space in what has been converted into a 36-story, 571-unit multifamily building.

“The immediacy of conversions is what intrigues me,” said Nathan Berman, founder and CEO of Metro Loft, which developed the property with Silverstein Properties. If a developer wanted to produce all of those apartment units from scratch, “it would still take you probably seven to nine years to pull a building of this size out of the ground in New York City,” Berman said.

But converting office into residential has a much quicker time frame. Metro Loft — which specializes in these projects — closed on the building with Silverstein last August for $180 million, and started renting units just a few weeks ago. Berman anticipates that tenants will move in by the end of the year. Rents in the building start at $4,100 a month for studios.

Upon settling into their new apartments, tenants will find kitchens with quartz countertops and bathrooms with Italian tile, as well as in-unit washers and dryers. Outside of the apartments, the building includes 25,000 square feet of amenities, with a rooftop pool as its hallmark feature. There’s also a fitness center, coworking lounge and pet-washing station.

Each of these features marks a new beginning for 55 Broad, which has been completely repurposed from its office origins nearly six decades ago. Excluding the lobby — which had previously been refinished and therefore utilized in the new residences — Metro Loft overhauled the building entirely, with one major goal in mind: LEED certification.

As a “zero-emissions, fully electric property,” said Berman, 55 Broad has pursued LEED certification by widely eliminating the mechanical systems of the original office tower. That means Metro Loft said goodbye to the building’s cooling tower and boiler plant, and disconnected from Consolidated Edison steam. While ConEd still provides electricity, the building has no gas; even its stoves are electric. However, 55 Broad retained a few of its original elevators for residents.

These electric-powered features have set a precedent for Metro Loft’s future conversions, though they didn’t arise out of tenant demand so much as out of environmental awareness, economics and the impending consequences of New York City’s Local Law 97, said Berman.

“We kept nothing but steel and concrete and, obviously, the exterior facade,” he added, noting that the windows are also new.

Yet one of the most significant throughlines at 55 Broad is perhaps the building’s lack of throughlines between units. The property reduced the openings between apartments to minimize the amount of air that travels from unit to unit. Before COVID-19, people didn’t think much about air circulation, said Berman. So, if somebody was smoking even two floors below, you could still potentially catch a whiff of cigarettes in your own apartment.

“Post-COVID, that isn’t something that’s very attractive,” he said. The new 55 Broad has penetration between its floors only in waste lines, which are insulated and waterproof, according to Berman.

“There’s virtually no air passing from one apartment to the other, and everything else is localized to the unit,” he said. “Even our kitchen and bathroom exhaust is through the exterior wall, through the facade.”

Anna Staropoli can be reached at astaropoli@commercialobserver.com.