Why CMBS Financing Has Come Roaring Back in Commercial Real Estate

Three decades after its creation, here’s why commercial real estate still reaches for CMBS financing despite the headaches when things go south

By Brian Pascus June 5, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

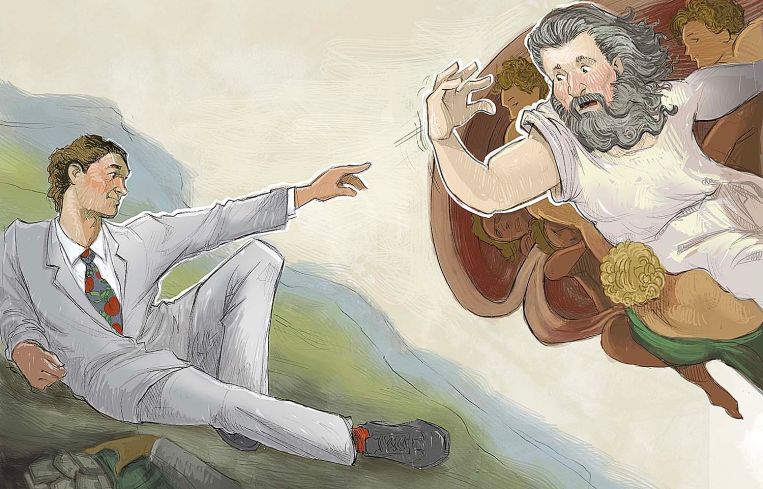

F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote that “there are no second acts in American lives.” And while the author of The Great Gatsby might have been referring to actors, auteurs and elected officials, he clearly missed the boat when prognosticating the resilience of commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS).

Through the first five months of 2024, the CMBS market is not only back, but thriving.

A year after issuance of conduit CMBS — multi-asset, multi-borrower deals — declined by 27 percent on the year, and issuance of SASB CMBS — single-asset, single-borrower deals — declined a whopping 73 percent, per Commercial Real Estate Finance Council (CREFC) data last October, originations have completely reversed course.

Year-to-date 2024, U.S. private-label CMBS issuance totals $32.2 billion compared to $13 billion during the same period in 2023, according to CREFC. CMBS issuance reached $12.2 billion in the first quarter of 2024, up nearly five times from the $2.7 billion in CMBS issuance in the first quarter of 2023, according to Blackstone.

This unexpected second act coming from this small but significant corner of the capital markets board — CMBS represents 14 percent of all U.S. CRE lending — could have vast ramifications.

Especially since investors have flocked to the nebulous security product — $24.6 billion in new CMBS securities have been purchased year-to-date through May, nearly three times the amount the first five months of 2023 experienced, according to Moody’s Analytics.

“I’ve been in CMBS for 30 years, and I have borrowers who say, ‘I’ll never do this again,’ and then we’re having a closing dinner,” said Michael Cohen, managing partner of Brighton Capital Advisors, a CMBS restructuring specialist. “I say, ‘Remember 10 years ago?’ But in this marketplace it’s any port in a storm.”

Richard Fischel, Cohen’s partner at Brighton Capital Advisors, said it’s the cost of capital that has made the often-loathed financing source the weapon of choice for CRE borrowers today.

“They have short memories,” he said, laughing. “Everyone says they’ll never do a CMBS loan again, and then someone comes to them with one and they’re 25 basis point cheaper than the alternative, and they jump right back in.”

Perversely, borrowers of the securitized loan and investors in the multi-tiered, fixed-income product have decided to re-enter the ever-complex, poorly understood CMBS waters at a time when defaults are increasing. The Trepp CMBS Special Servicing Rate increased by 80 basis points in April 2024 to 8.11 percent, its largest monthly leap in four years, since the depths of COVID in mid-2020.

So why on earth would any discerning borrower, let alone sensible investor, choose to bet their bottom dollar on the U.S. CMBS market?

“Why do bank robbers rob banks? It’s where the money is,” said Peter Stelian, CEO and co-founder of Blue Vista, a CRE investment firm. “If you need money and are in position to refinance a loan and you don’t have an alternative, it becomes your go-to source and potentially your only source for financing.”

Filling the void

Within the universe of CRE finance, there are four main branches of liquidity: life insurance companies, commercial banks, debt funds and CMBS capital markets (which is basically a self-contained bond market). All four sources are necessary for liquidity to flow and for the system to function, but there are periods when one leg of the lending sphere is more attractive than another one.

Right now — largely for a mix of macroeconomic reasons — CMBS is having its moment, again.

Stelian identified the pullback in commercial bank CRE lending as the primary culprit for the rush to CMBS. On the heels of the 2023’s regional banking crisis — which saw Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic Bank go under in quick succession — and the near death of New York Community Bank this January, many commercial lenders have closed their windows and battened the hatches in anticipation for further distress across the CRE sector.

After closing $595 billion in CRE loans in 2022, dedicated commercial lenders closed $306 billion in CRE loans in 2023, a decline of 49 percent, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association.

What’s replaced traditional CRE balance sheet lending has been a wave of new CMBS issuance from the biggest players on the block — Goldman Sachs, Bank of America, Wells Fargo, J.P. Morgan Chase, Citi — whose fortress balance sheets can originate massive CRE loans and securitize them into a structure-rated product for investors desperate for investment-grade paper and a lucrative fixed-income vehicle.

“Banks are in retrenchment mode so there’s a huge liquidity crisis that’s going on, and CMBS is stepping to fill that liquidity crunch,” said Stelian. “It’s a combination of a gap in the market because of regulatory pressure, credit pressure and balance sheet pressure.”

Marcello Cricco-Lizza, a portfolio manager at Balbec Capital, noted that a lot of CRE transactions were put on hold during the second half of 2022 and most of 2023 as interest rates rose, and those transactions need to come to market today. Moreover, he said that the biggest factors driving CMBS issuance are acquisitions and refinancings by the world’s largest private equity firms like Blackstone.

This year, the trillion-dollar behemoth based at 345 Park Avenue refinanced a portfolio of 100 industrial properties with a $2.35 billion CMBS debt package in March, and closed a $428.5 million refinance for a portfolio of 23 hotels in April. All told, Blackstone’s CMBS refinancings are expected to approach $12 billion before we reach December.

“CMBS has had a rally so far to start this year,” said Cricco-Lizza. “Money market managers are back in the market buying risk in sectors where there are significant tailwinds, like data centers, logistics. And in multifamily you’re seeing healthy issuance.”

Christopher Herron, a managing director at Iron Hound Management, which specializes in CRE debt arranging as well as CMBS restructurings and workouts, pointed instead to the Federal Reserve and larger interest rate environment for the flight of capital to less expensive CMBS in 2024. Today the federal funds rate stands at 5.5 percent, nearly 500 basis point higher than in February 2022, while the 10-year Treasury note, which CMBS trades off, sits at 4.62 percent, nearly 100 basis points higher than in December 2023.

“Not everyone, including the Fed in their own statements, believed that interest rates would stay as high as they have for as long as they have,” said Herron. “Come 2024, as the reality of an increased interest rate environment set in, the pent up demand for CMBS issuance, along with the need to transact by borrowers, led people to understand that the higher cost of capital was here to stay.”

The price of success

While the cost of capital might be elevated for CRE market participants, it is still relative for all parties involved.

As of late May 2024, the 10-year super-senior (SS) AAA fixed-rate CMBS product priced at 131 basis points over the 10-year Treasury; this compared to a year-to-date 2024 widest spread of 159 basis points over the 10-year, according to CREFC.

Further down the investment-grade CMBS credit curve, spreads on BBB conduit pieces have tightened from a whopping 918 basis points over the 10-year Treasury at the outset of 2024 to a more palatable 696 basis points as of May 24, 2024, per CREFC.

This spread over the Treasury is the key to understanding CMBS economics, as the spread indicates what the borrowers will pay on their loan, what investors will yield on their purchase, and what the lender stands to make on its newly securitized product. While it might not seem significant, these gradual basis point reductions make it substantially cheaper for borrowers to finance their CRE assets — in turn opening up capital markets activity.

“The borrower is getting a lower borrowing rate as the spread has come down and the investors are seeing a lower yield in investing in the class,” said Joe Seydl, senior economist at J.P. Morgan Private Bank. “There’s still a healthy spread above Treasurys, but between the peak of last year, when we were looking at over 1,000 basis points over [the spread of Treasurys], and today, it has compressed. It’s a healthy spread.”

For CMBS lenders, originating in a world where regional banks have run for the hills, even a compressed spread up to 700 basis points higher than the 10-year Treasury sitting at 4.62 percent is the equivalent of giving “the only game in town” a monopoly on chips and booze, if not chairs and cigarettes.

“If the question is, ‘Why are spreads so high?’ You can charge these spreads because there are not a lot of offerings out there,” said Brighton Capital’s Cohen. “You’ll charge as high a spread as you can in the marketplace to do that loan because you know the borrower doesn’t have as many options.”

Fischel said that higher spreads are always lucrative for lenders, who charge interest paid on the loan based on the difference of what they’re buying the money for and what they’re selling it for.

“A lot of times, spreads for CMBS were historically in the 50 basis points range,” said Fischel. “If they’re making 250 basis point spreads, that’s a huge profit for them.”

Dylan Kane, managing director of Colliers Capital Markets Group in New York, said that many regional banks and commercial banks are dealing with existing portfolio issues — especially borrowers struggling to repay, receive maturity extensions, or achieve healthy debt service coverage ratios — and have paused new originations to focus on existing assets.

“Your options as a borrower, particularly from traditional banks, have dried up materially, compared to the CMBS market, which is still very liquid,” explained Kane.

“While it does come with some headaches when dealing with an asset that underperforms, or goes into special servicing, overall CMBS is available and a better option than it was last year,” he added.

Who needs it?

The idea that CMBS is a better financing option than balance sheet lending is far from axiomatic. This is largely due to the labyrinthian structure of even the most basic CMBS conduit security — which typically features several different asset classes at several different values in several different markets all packaged together — and the innumerable problems that occur when one part of the bond defaults, bringing borrowers into the clutches of the special servicer, master servicer and controlling class holder — which sound like a motley crew of D.C. Comics supervillains.

“The reality is the CMBS loan has more cooks in the kitchen than the loans held on balance sheets,” said Herron. “But certain investors understand that for certain products, there will always be a need for CMBS. Whether leverage, interest-only, pricing or term, there are structural characteristics found in CMBS, not found elsewhere, that keeps everyone coming back, despite the occasional headache.”

If borrowers are attracted to spreads and pricing, then investors flock to CMBS and fuel future originations by buying into a cantilevered arrangement of rated and regulated loans divided into tranches sorted by risk. The safest loans within the conduit bond pay off first but offer lower yields, while the riskiest loans pay off last, take the first loss upon default, and pay the highest yields upon maturity.

“CMBS was made for two reasons: one, you’re taking apples and making applesauce. Some may have a worm, some may have a scratch, but the diversification, range of location, borrowers, gives [investors] far more comfort,” said Cohen. “And, second, a lot of the institutions that buy these realized that if I own a whole loan and the world goes bad, then I’m stuck with these things, so it’s better to have it [securitized].”

Lenders, particularly for large SASB deals, gravitate toward CMBS because they don’t have to house the loan on their balance sheet. They go to the market, pre-sell it, and close the same day to avoid the balance sheet risk.

It was actually this appeal to lenders that led to the birth of the modern-day CMBS in the early 1990s. Ethan Penner, managing partner of Mosaic Real Estate Partners, is often credited with creating the CMBS market during the widespread CRE distress that emerged following the savings and loan crisis of the late 1980s and the rise in interest rates from 1988 to 1990.

Penner saw that traditional lenders and insurance companies had voluntarily dialed back their exposure to CRE during the early 1990s recession, which generated an unmet need for some new source of financing — anything — to fill the void for billions of dollars in CRE loans requiring either refinancing or fresh capital for acquisitions and construction.

“The CMBS market was created by me for exactly this reason, and by introducing the bond market to the CRE community, I was able to fill that void,” recalled Penner. “Unlike the regulated lenders, the bond market isn’t an on/off switch. When a regulated lender is told by a regulator not to lend, they don’t lend. But the bond market isn’t governed by regulators: It’s always on, even though its price and risk profile might change.”

Working with S&P and Fitch to create a ratings foundation, Penner approached Nomura Securities in 1993 to create the nation’s first CMBS lender, closing $3 billion in deals that year and inaugurating the genesis of Wall Street’s participation in CRE finance, as banks are nothing if not hounds for new money products.

“Until that time, Wall Street had no exposure to CRE — firms like Goldman Sachs, Lehman Brothers, Morgan Stanley followed my lead a couple years after,” said Penner. “And there’s always money at some attachment point. That’s the gift of securitization: the introduction of a more consistent source of capital to the real estate industry.”

If CMBS has given investors, borrowers and lenders the “gift” of securitization, it has also added the curse of complex workouts that plague borrowers, confuse bondholders, and destroy the confidence of investors.

Unlike with balance sheet loans, the bank originating the CMBS loan loan is merely a pass through. The ultimate lender is the bond itself, or everyone in the bond — from the AAA investors to the controlling class holder (CCH) — who are the true lenders, because they bought the loans. The master servicer and special servicer are just agents on behalf of bondholders, who have very defined roles based on pooling and servicing agreements. For borrowers, these servicers and the CCH are the only parties they interact with during the life of the loan, and are their only means to fixing any problems to arise during a default.

As for the investors, they stare into a black hole, as those players are buying securities and are only left with faceless metrics to compare underwriting across different slices of the loan — leaving only the CCH, who has bought into the highest-risk, first-loss position, as the only bondholder with any influence on the capital structure of the CMBS security — and that person is taking recommendations, if not orders, from the special servicer.

“Bond buyers are buying a coupon and rating, and, in a perfect world, there’s no defaults because everything is underwritten property and you’d just be taking the cash flows from the properties and dividing them through bond stakes as applicable,” explained Fischel. “But we’re in business because of this structure. The borrower has no clue what is going on.”

Brian Feil, principal at The Feil Organization, a CRE investment and development firm, presently has two CMBS loans on buildings being worked out with special servicers: a $10 million deal and a $105 million deal. Feil said he’s been waiting six months to receive a response from the special servicer on the workout, and that during this time his buildings have lost tenants and bled value as the special servicer collects fees for every month the loan sits in their hands.

“It’s beyond frustrating, and I’ll say that nicely,” said Feil. “There’s zero alignment. They are slow and unreceptive to working out any issues until they have to. … They don’t care if they aren’t protecting the asset value. They’re just working to make their fees. There’s a misalignment in terms of what they’re doing.”

Distress test

This misalignment is at the heart of CMBS’s inherent contradiction in the grand scheme of capital markets. And it has become glaringly apparent during a time of high distress.

Take the example of 1740 Broadway in Midtown Manhattan. Its $308 million SASB CMBS note had already defaulted and was sold on May 23 by the special servicer and owner Blackstone to Yellowstone Real Estate for $188 million, a deal that generated only $117 million for bondholders and in turn wiped out all creditors in the lower-ranked tranches and dealt those in the AAA position holding $158.3 million in securities a shocking loss of $40.3 million in aggregate.

When a CMBS loan, like the one secured by 1740 Broadway, faces the threat of default, the junior bondholders, namely the CCH, don’t want to take any loss, so they’re inclined to come to the table with the borrower and give them an extension or a workout to keep things humming. But the senior bondholder doesn’t want that. They’ve bargained for AAA risk, and are willing to cut a deal at any price to get their money back and escape. Through it all, these bondholders rely on the special servicer to litigate all matters.

“Therein lies the fundamental conflict for the borrower, the deal and the trust who has issued different bonds with disparate interests: Whose interest is the special servicer trying to protect?” explained Penner. “Is he trying to protect the value of real estate, or the junior bondholders’ interest from loss, or the senior bondholders? Depending on how you answer that question, you would act very differently, and that question isn’t normally asked in good times.”

And it doesn’t take a glance at the headlines to recognize that these are not good times for commercial real estate, especially for the office sector.

In the pre-COVID times, up to 90 percent of office sector CMBS loans paid off at maturity. Last year that ratio fell to 35 percent, according to Moody’s.

Over the next year, Moody’s predicts that $18 billion in office loans converted into CMBS securities are expected to mature.

Lisa Pendergast, executive director of CREFC, said that many of these loans coming due in 2024 originated in the 4 percent area and as five-year loans during the pandemic. Now borrowers are facing refinance rates that are some 300 basis points or higher than their current rate.

“The key issue with outstanding CRE and multifamily loans is today’s sharply higher benchmark and CRE mortgage rates,” said Pendergast. “Adding to this, any assets that have been negatively impacted by the pandemic, like office, are even more challenged in a refinancing.”

Plus, defaults might gradually worsen throughout the decade due to the 10-year structure of most office loans, and the fact that originations cratered in 2022 and 2023. For example, one of the worst years of origination in CRE history, 1986, was due to overbuilding, but the losses didn’t peak until the early 1990s, according to Moody’s Joe Baksic.

“Loans don’t default immediately. It takes certain events to happen, and if a borrower does default, the lender might not want to liquidate immediately, they often want to hold onto an asset until they can sell it at better times,” said Baksic. “There’s often a lag effect between loan delinquency and asset values.”

Devolution or evolution?

As for worries that CMBS will take down the global financial system the same way residential mortgage-backed securities, collateralized debt obligations, and credit default swaps did back in 2008, there is very little risk for a full-blown economic meltdown. That’s because of the ways CMBS has evolved since the Global Financial Crisis.

Both Fischel and Cohen, who’ve been involved with CMBS since its inception in the early 1990s, said that CMBS 1.0 (early 1990s to 2008) didn’t have a third-party overseeing the special servicer, which created concerns that the special service wasn’t acting in the highest interest of the CMBS trust. Today, we’re in CMBS 2.0 (or 3.0, depending on who you talk to), a post-GFC era that features scrutiny from both rating agencies and independent third parties, but also the wrinkle of supercomputer financialization.

“It’s become more regulated, it’s become more oversight-driven, more analytical, more data-driven,” said Fischel. “You sort of have guys who have been in the [CMBS] industry who are multigenerational, so it’s becoming more focused, but what always happens is something happens that no one can anticipate.”

Colliers’ Kane said that CMBS 3.0 carries the hallmark of five-year securitizations, whereas CMBS 1.0 and CMBS 2.0 relied on 10-year deals. Moreover, many new originations are made with four-month to six-month open pre-payment periods. These adjustments are a strategic move to market to borrowers who believe interest rates will decrease in the near term and hesitate to lock in terms for the typical 10-year period.

“That’s how the product has evolved most recently to accommodate borrower demand,” said Kane.

Another CMBS expert, who requested anonymity, described changes to the Fair Market Value Option (FMVO) — which had afforded the CCH to ability to purchase the loan out of the trust at a loss — as an innovation that gives independent appraisals, and not the CCH, the means of determining whether an asset is impaired before control shifts within the securitization to the CCH.

The expert said “It’s sort of too early to tell” whether the appraisal method is a more efficient way of working through impairment than the previous FMVO option.

But the godfather of CMBS, Ethan Penner, doesn’t believe that his popular, if maligned, security product has evolved much since he came up with it in 1992, with the key unresolved weakness being the tension of how to settle nonperforming loans upon maturity defaults.

“There are fundamental flaws that were built into the system,” said Penner. “The junior classes benefit from forbearance and the senior classes benefit from foreclosure, and there’s a tension there that has not ever been addressed properly in the CMBS system.”

As for the future of CMBS, it seems safe to say that even as office distress creates more defaults and an uptick in special servicing rates, the risk within capital markets must be distributed to investors. As sponsors remain wedded to refinancing their loans, there is only one fixed-rate product that can cover the amount or real estate loans that exist in the world today.

“There’s not enough balance sheet in the country for all the outstanding CMBS to sit on one person’s book,” said Herron. “The CMBS market will always exist to distribute this risk.”

Brian Pascus can be reached at bpascus@commercialobserver.com