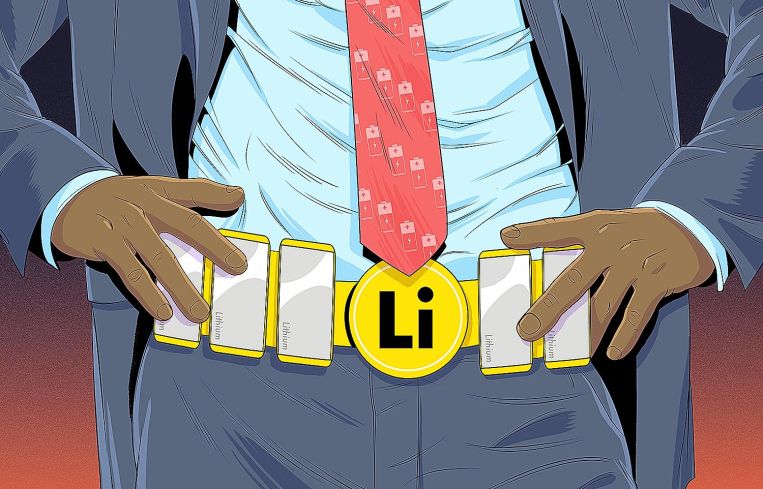

The Southeast’s ‘Battery Belt’ Is Big for Commercial Real Estate

Around half the nation's planned or underway EV plants are in a handful of states that may not be able to handle the overload

By Patrick Sisson January 22, 2024 6:00 am

reprints

In Elizabethtown, Ky., and the surrounding cities and towns of Hardin County, one of the biggest economic drivers has always been Fort Knox, a massive military installation famous for holding the nation’s gold reserves.

A new battery manufacturing campus beginning to take shape in Glendale, the BlueOval SK battery plant, shows the region striking gold once again. A joint venture between Ford Motor Company and South Korean firm SK On, the twin 4 million-square-foot facilities will be one of the 10 largest such projects in the world when complete, generating a jobs boom and building bonanza for the surrounding area.

“We’re already seeing the growth,” said Margy Poorman, president and CEO at the Hardin County Chamber of Commerce. “We are seeing that farmland gets purchased with the anticipation of building single-family homes. They’re building apartments and luxury apartments in that area. Commercial and industrial property has also been snapped up very quickly in our area.”

Despite its impressive size, BlueOval SK represents just a fraction of the manufacturing and industrial investment sweeping over Southeastern states such as Kentucky, Tennessee, South Carolina and Georgia. Thanks to the generous incentives in 2021’s Inflation Reduction Act, roughly 77 EV projects nationally, representing $80 billion in investments and just shy of 50,000 jobs, have been announced so far, according to a recent Cushman & Wakefield report, with half of those in this Southeastern region dubbed the Battery Belt. This flood of funding from a new era of national industrial policy will help a region that’s already seen an automotive and auto parts boom hit second gear in recent decades.

“The scope is so broad that it touches every aspect of personal life and the corporate and commercial real estate world,” said Christa DiLalo, Cushman & Wakefield’s Southeast research director. “The Southeast is so well positioned to take advantage of the timing of these opportunities. Right-to-work laws make them attractive to companies, and local leadership understands the opportunities available.”

This means tangential opportunities for commercial real estate to provide new workforce housing, warehouses, retail space and additional manufacturing facilities beyond the plants themselves. These opportunities are, in effect, drawing a new map for developers, delineating the location of EV and battery plants, inland and ocean ports, and population centers, where industrial and commercial development will take off. A May 2023 study by the Center for Automotive Research estimated that for every job created at a Hyundai EV plant, for instance, 3.7 additional jobs will be created in the surrounding region. A consultant study estimated that in Hardin County alone, 22,000 new residents will require the creation of nearly 9,000 new housing units.

“Anywhere rural where you get really crowded really quickly with thousands of manufacturing jobs, most of which pay pretty well, means you’re going to have a pretty decent amount of people with disposable income all of a sudden,” said Seth Martindale, a CBRE senior managing director focused on site selection.

Cities such as Atlanta and Charlotte will see additional benefits from regional growth. Corridors between plants, like the area between Charleston and Columbia, S.C., or from Atlanta to Chattanooga, Tenn., where additional warehouse and manufacturing sites will be in high demand, will see increased land values, investments and developments. Built-to-rent housing is expected to follow in the footsteps of the burgeoning EV business.

A good example is Savannah, Ga., where a new 12 million-square-foot Hyundai plant is under construction. Between the new workforce that facility will attract and activities at the city’s port, the area has become one of the most sought-after markets for multi-

family development in the Southeast, DiLalo said, with some of the highest rental growth projections over the next five years.

Many of the plants and projects that will benefit from the IRA have been announced and are under construction, which will create cascading real estate demand. Once the electrical hookups and infrastructure for these plants are complete, it opens up opportunities for additional development along these corridors and roadways. It’s likely that multifamily and retail projects timed to plant completions won’t start for months, since these plants will take significantly longer to complete. Martindale predicts most plants are at least a year or two out from operating, giving real estate developers and investors time to strategize and to acquire financing.

Like similar economic booms, this EV gold rush comes with some caveats. Significant workforce challenges, as well as high demand for electricity hookups, might delay some projects. States and localities have long struggled with providing these basic building blocks for economic growth, said Martindale. He also cautioned that national developers trying to swoop in and work in exurban and rural areas they’re not familiar with might encounter headaches, since they may not have the same regional political and government connections as local developers.

One significant issue, then, may be the sustainability of the growth. Dollar figures that companies and consultants throw around are based on growth projections of plants running at full capacity. That’s not certain considering wariness in some corners around EV demand, as well as general uncertainty about the overall economy.

There’s also the issue of tax incentives and their impacts on local development. Kasia Tarczynska, senior research analyst at nonprofit Good Jobs First, which tracks corporate incentives from all levels of government, said these subsidies, currently measured at $19 billion across 36 projects, are unprecedented in terms of the last half-century of industrial policy. She points out that the money flowing into these EV projects — especially state and local sources — comes from somewhere, usually out of budgets for schools and local infrastructure and services.

New developments and growing population centers will need good schools and public services to attract workers, and these kinds of economic development incentives tend to starve local governments of needed resources. As Tarczynska puts it, it’s effectively creating a magnet for growth without a sustainable way to pay for it.

Similar projections around growth and infrastructure needs have been penciled out for Hardin County, which will require new schools, hospitals and roads, per consultant estimates, as BlueOval takes shape. But at the same time, there’s palpable excitement about the potential for change, both in Glendale, a small town without a single stoplight that will soon be home to this massive facility, and surrounding cities and towns.

“It’s easy to throw out numbers, like millions of square feet or billions of dollars, but there are real figures and real people coming,” said Poorman. “That comes with a big responsibility, but I think the community is ready for it.”