Proptech’s Hot Takes On SVB’s Bank-Run-and-Done Shocker

Real estate startup experts survey the damage, vent their anger, and look to future financial fireproofing

By Philip Russo March 17, 2023 9:00 am

reprints

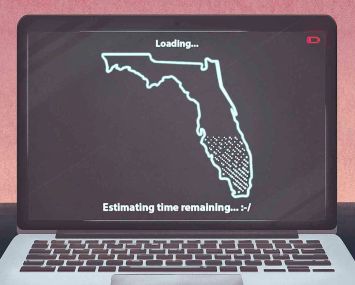

The spectacular collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) does not spell doom for proptech’s ecosystem, but over one shocking March weekend it gave the sector’s founders and venture capitalists a warp-speed business experience of the five stages of grief.

As if taking lessons from the 1969 Elisabeth Kubler-Ross book On Death and Dying, a vast array of proptech professionals suffered some degree of denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance upon hearing the news of SVB’s failure, and subsequently that of Signature Bank, which has its own dubious history beyond tech startups.

Let the finger-pointing begin.

The hot takes from the financial and political spheres focused on SVB’s lack of risk management, pointing to its overloading on long-term Treasury bonds in the face of rapid and repeated interest rate hikes that devalued them as key to its downfall. Signature Bank (SBNY) was faulted for its over-reliance on shaky cryptocurrency company depositors, while a 2018 congressional move to weaken the Dodd-Frank Act lit the long fuse that resulted in the two banks’ conflagration, according to U.S. Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

“We don’t even bank with SVB, but I’m angry right now,” Sonny Tai, CEO at Actuate, a Manhattan-based security analytics proptech startup, said in a response for this story on LinkedIn. “Imagine being a founder or an early employee and having your company that you’ve poured years of your life building killed by a bank run because panicked venture capitalists went and created a stampede by telling their portfolio companies to pull their deposits.

“They were essentially telling their portcos to trample on the bodies of other founders and to rush for the exits. It’s all good as long as you get yours, right? Considering that half of all venture-backed startups bank with SVB, there’s a lot of companies whose futures are uncertain right now because of selfish and myopic decisions.”

Other proptech entrepreneurs expressed varying degrees of opinion and transparency relating to SVB’s demise.

“I can confirm we are notifying our customers that had payment instructions directed to a SVB account to make payments to an alternative account at a different financial institution,” said Steve Lombardi, vice president of communications and business affairs at Matterport, a Sunnyvale, Calif-based spatial data company.

While declining to confirm that his proptech company had accounts with SVB or Signature Bank, Rasheq Zarif, co-founder and COO of ReWyre, a proptech procurement platform, responded in writing: “SVB played an important role in supporting and catalyzing American innovation. Many startups would not be where they are today without the support it provided.

“That said, those who think this spells disaster for the proptech sector are mistaken. SVB is not the only ingredient to continued industry success. Proptech will push on, helped by a clear and growing need for more sustainability, as well as the digitisation of outmoded processes and systems across the real estate life cycle.”

Zarif isn’t alone in his optimism.

“We were an SVB customer, so Friday was certainly a nerve-wracking day, and through the weekend,” said Brent Steiner, co-founder and CEO at Denver-based Engrain, a property touring and mapping startup. “RET Ventures, who led our Series A round, were also in SVB.”

Despite SVB’s collapse, Engrain and RET closed the funding round, said Steiner.

“I think it’s hard enough to do what companies like ours have to do, and these curveballs just keep coming out of nowhere,” he said. “We’re glad to have it behind us.”

Engrain “only had a few million dollars in the SVB account at the time, thankfully,” said Steiner. “But I know many CEOs who have been affected majorly, not knowing what they were going to do coming into this middle-of-the-month payroll week.”

However, Steiner saw a “silver lining” in the banking debacle: “Watching the community rally around these companies to make sure that they’re OK, working together, and at least being prepared for a less desirable outcome, but ultimately having it resolved.”

Nevertheless, Steiner was shocked by the speed of SVB’s failure.

“They seemed to get caught [between] rising interest rates and maybe some questionable bond decisions that caught them on their heels,” he said. “And, then, obviously, I think the smartphone effects of this were when certain VCs caught wind of it, word spread, and then, boom, it fell.”

SVB was especially attractive to tech startups because of the bank’s perceived understanding of the companies’ financial needs, providing the young businesses with greater lending and credit line flexibility. Now that SVB is gone, the banking alternatives for tech startups are more difficult to find, said Steiner. (And proptech generally was already dealing with a decline in VC investment. Global investment dropped 38 percent annually, to $19.8 billion, in 2022, according to the Center for Real Estate Technology & Innovation.)

“We worked with Chase before and Chase has been a great partner, but they’re definitely much less flexible,” he said. “So I think it’s a bit shocking that it can happen that quickly, but I think that FDIC covered the [situation], thankfully, as it should have. It sounds like the powers that be will be taking a look at ratios and things that need to be updated to prevent it from happening again. But, ultimately, it feels like it’s a symptom of the speed of communication that we just didn’t have in past decades.”

SVB’s domination of proptech startup banking is what makes its collapse so profound, said Steven Adler, CFO at Upflex, a Manhattan-based flexible office space startup that had “less than $10 million” deposited with the bank.

“SVB had a unique position in the early entrepreneur environment, including proptech,” said Adler. “It was unbelievably friendly. They were easy to bank with. They gave us credit facilities and credit cards. So you literally could start a business tomorrow, get a VC to invest in you, and SVB would bank you and give you credit cards and lines of credit up to a third of the capital raised.”

SVB’s financial impact was “unbelievably beneficial for the venture community because they would give us lines of credit for companies that were losing money,” Adler said. “Nobody else would give you a loan. That’s going to be the final outcome that people don’t realize is the biggest impact. It’s the additional liquidity that all of us got — between 20 and 33 percent more money.”

Other banks don’t have all those services for startups, he added.

“Chase has never been really friendly to the startup,” Adler said. “That was the critical component that Silicon Valley Bank (SIVBQ) played in helping all the venture capital-funded companies, and now it’s going to be way harder. We’re now in the middle of opening new bank accounts, credit cards, and it’s really complicated.”

However, SVB’s largess toward startups wasn’t without what turned out to be potentially dangerous banking constraints for the customer.

“In order to get an SVB credit facility, you had to do three things,” explained Adler. “All your banking had to be done with SVB. Your credit facility had to be with SVB. You couldn’t have any facility anywhere else. If you do have venture debt on top of it, they’re going to have an inter-creditor agreement. Third, all your credit cards had to be with SVB, so you’re what I call all in.”

The result was what looked like an irresistible bank for proptech startups, with reportedly at least half the new companies banking with SVB. “I think the number is closer to 75 percent,” said Adler.

Now, however, proptech startups’ boards of directors that include their funding VCs won’t allow such an “all-in” arrangement with any bank, he added.

“They’re going to mandate that we have banks like First Republic, UBS and Chase in addition to a SVB, including at least one bank that is too big to fail such as JP Morgan, Bank of America or CitiGroup.”

Ultimately, even though Upflex took proactive steps to remediate the situation, the company’s funds were already frozen, along with 37,000 other impacted small businesses that had deposits in excess of $250,000, said Adler.

Worse still, the reverberations of these collapses will be felt worldwide, he added.

“The collapse affected not only companies in the United States, but also thousands of tech companies in the United Kingdom and Israel, in addition to all of the vendors that each of these companies work with.” Adler said. “Payments will be delayed to tens of thousands of vendors, including many small businesses who service the startups impacted by these collapses.“

Let the finger-pointing continue.

Philip Russo can be reached at prusso@commercialobserver.com.