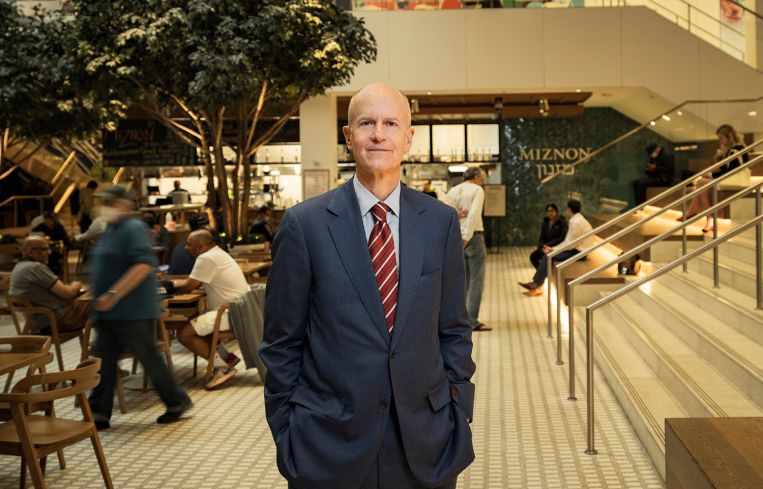

Boston Properties’ Owen Thomas Doesn’t Fear Work From Home

CEO of America's largest publicly traded REIT focused on offices remains bullish on their role

By David M. Levitt July 12, 2022 9:00 am

reprints

It’s been Boston Properties’ mantra since just about the very beginning: A-properties in A-locations.

What it means, and has meant since founders Mort Zuckerman and Edward Linde started the company in the early 1970s, is latch on to the very best skyscrapers in the very center of a small group of heavily studied, well-recognized markets. The world will repeatedly beat a path to them. Let others take the risk of developing in broader or emerging markets.

And it’s still the mantra of Boston Properties, says Owen Thomas, the man who today runs America’s largest publicly traded real estate investment trust that specializes in offices. Damn the torpedoes, the lagging return-to-office rates, the laptops, the widespread and novel notion that while it’s nice to have a wonderful, well-appointed office, it’s no longer essential. Full speed ahead!

“It’s more important today than ever,” Thomas, 61, said in an exclusive late June interview with Commercial Observer. “Our clients increasingly are working with us to encourage, entice their workforces to come back to the office. There are many ways that that’s being done, and certainly one is being in the highest-quality buildings that are easily accessed by transit, that are highly amenitized. That’s been our strategy since our founding, and that strategy is helping us in this environment.

“We do not need to radically change our strategy,” he said.

Investors aren’t so sure. Boston Properties closed on July 5 at $91.16 a share, down more than 30 percent since late March, when it set a post-pandemic high of $132.51 (its all-time high of $143.35 was set just before the pandemic, in January 2020). It was widely regarded as a financial fortress, an impeccably run company that controls some of America’s best-known and most lucrative pieces of real estate, including New York’s General Motors Building and what used to be known as Citigroup Center — now 601 Lexington — the tower with the slanted top; Boston’s Hancock Tower and the Prudential Center, both the city’s tallest spires and the former designed by Henry N. Cobb; San Francisco’s tallest building, the Boston Properties-built Salesforce Tower; and Washington’s glassy 601 Massachusetts Avenue NW.

During roughly the same period, late March through the start of July, the S&P 1500 Office REIT Index lost about 40 percent of its value. So Boston Properties isn’t alone among REITs confronting stock volatility.

Nor is it alone among office owners in general in confronting naggingly low occupancy. Kastle Systems’ “Back to Work Barometer” tracks security card swipes at office buildings in 10 major markets. The most recent reading before press time, for June 29, was a lackluster 43.8 percent, an occupancy level just shy of a post-pandemic high of 44.2 percent the week before. In Boston Properties’ markets, New York was at 41.2 percent, San Francisco at 34.7 percent, Los Angeles at 41 percent, and Washington at 40.2 percent. (Kastle doesn’t report Boston or Seattle.)

During its most recent earnings conference call in May, Thomas described its “census” of workers actually coming into and occupying its buildings as between 40 and 80 percent, a difference you can drive a truck through. Asked to narrow it down, he declined, but said the rate was improving.

“What we’re experiencing is more people in the office Tuesday through Thursday and less Monday and Friday,” he said. “Peak day is the way we look at it. We acknowledge that hybrid work is likely a durable concept. A lot of companies are saying to their workforce, ‘We want you in here three days, four days, but we want everybody in some days.’ If everyone is not in the office, the collaboration benefit goes away.

“The big variation on the census is by geography,” Thomas said. “We see the most in-person work going on in New York City, and the least in San Francisco. That is related to a couple of different things. One, there is a greater financial service component of our client base in New York, and in San Francisco it’s more technology. And, second, San Francisco and California stayed closed longer than the rest of the nation on COVID.”

IBM’s CEO, Arvind Krishna, told CNBC in June that only about 20 percent of its U.S.-based workers are back in the office three days a week, and he thinks it will never reach as high as 60 percent. And Yelp, the popular online customer review site, announced that it intended to close its offices in New York, D.C. and Chicago, its CEO, Jeremy Stoppelman, writing in a June blog post that “the future of work at Yelp is remote.” The company intends to keep its corporate headquarters in San Francisco open.

That 20 percent number from IBM “is lower than what I hear from other technology clients,” Thomas said. “What we’re finding with our clients is that workers that are client-facing, product-facing are in the office collaborating, and workers that are in support areas like IT, accounting, HR, those workers are not in the office as much, and are working more remote.”

What Thomas said is that Boston Properties is finding that while companies may not be demanding that all workers be physically present all the time, they still want a place where employees can come together, collaborate and learn corporate culture, and that can accommodate substantially all of their workforce. That can’t be done at home, or online, or from a coffee shop. There’s still a need for a place that identifiably belongs to Salesforce, the law firm Arnold & Porter, Akamai Technologies and Biogen, to name Boston Properties’ top four tenants, according to its first-quarter supplemental filing.

As of March 31, the company controlled 202 U.S. properties, totaling 53.9 million square feet, which were 88.8 percent leased, and yielding $2.9 billion of its share of annualized revenue (some properties, like the Brooklyn Navy Yard’s new Dock 72 building, are owned in partnership — in Dock 72’s case with Rudin Management Company).

While Boston Properties’ most-watched numbers — its occupancy rate, its funds from operations, its debt-to-revenue ratio, the yield on its development pipeline — have held up during the pandemic, Thomas said he was not worried about suddenly hitting a wall, such as if the company were confronted by a large number of tenants wanting to reduce their space all at once.

“Many of our clients are in the office three or four days a week,” he said. “Many of them are mandating that everybody be in the office on certain days of the week. So it’s hard to reduce space when that occurs.”

One strategy common to large commercial landlords that Boston Properties is abundantly engaging in is amenitizing its properties. The company has added gyms, coffee bars and bike rooms, and made sure its buildings have state-of-the-art lobbies. No one can use that as an excuse when it’s time to renew or extend a lease. For example, the General Motors Building — probably the best-located of Boston Properties’ buildings, at the southeast corner of Central Park, but also one the company’s oldest buildings, having been built in the 1960s — has a brand-new amenity center, Thomas pointed out, including a health club and conference facilities.

“We are always refreshing our portfolio,” he said. “We started the General Motors amenity center before the pandemic. I don’t know if you have come to the Hugh yet, which is our food hall at 601 Lex, which we started three or four years ago. It’s packed. It took me half an hour to get food yesterday over there at lunchtime.”

And Boston Properties is also building out lab space for life sciences companies, which are largely immune to the appeal of working from home.

Its strategies were recently endorsed by Tayo Okusanya, a REIT analyst at Credit Suisse, who wrote in a June 22 note that Boston Properties “provides a low-risk reopening play on a post-COVID return to office in Gateway markets.” He did note in his “grey-sky scenario” that the REIT runs the risk of “widespread adoption of hybrid work (leading) to a significant reduction in office demand” and that a recession could force office users to “right-size organizations and shed office space.”

Thomas cut his business teeth in banking, albeit banking that eventually intersected with high-stakes real estate. For 24 years, through 2011, he held various positions in the finance operations of Morgan Stanley, one of the world’s largest investment banks. It included leading Morgan Stanley’s real estate investing arm, which provided clients with access to value-add, opportunistic and core strategies to grow wealth. Such an arm exists in just about all of Morgan Stanley’s competitors, like Goldman Sachs Group, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and, until its bankruptcy, Lehman Brothers Holdings.

In 2005, Thomas was named president of Morgan Stanley Investment Management, under John Mack, who was then the bank’s CEO. While Morgan Stanley did hold an inordinate number of subprime mortgage securities in the Great Financial Crisis, it avoided the fate of rival Lehman in part by receiving cash infusions, including $5 billion from the China Investment Corp. and $10 billion of equity investments from the U.S. Treasury.

In 2011, creditors of Lehman chose seven professionals, including Thomas, to oversee the dissolution of the company. A year later, he was named the first chairman of the post-dissolution Lehman, and he remains on that board today, though a vast majority of its assets, including its real estate, have been liquidated. He withdrew from being chairman when he became Boston Properties CEO in 2013.

One characteristic of Boston Properties, even before Thomas arrived, is the slow and deliberate way it adds markets. It took years of analysis before it entered the Los Angeles market about five years ago, when it bought a position in the Colorado Center in Santa Monica. Similarly, it moved conservatively when it established a beachhead in the Seattle market with the acquisition of Safeco Plaza. In May, it acquired a second property in Seattle called Madison Centre.

Don’t look for it to enter markets like Nashville or Austin any time soon, even though such markets are the talk of the commercial real estate world as companies and residents decamp for them during the pandemic.

“I think our footprint is established for the foreseeable future,” Thomas said. “We went into Seattle last year, and Los Angeles four or five years ago, and both of those regions are contributing 2 to 4 percent each of our total result, and we want those regions to be bigger. We have a life sciences opportunity that we are also investing in, and that will be a bigger part of our company. So we’ve got plenty of opportunities.”