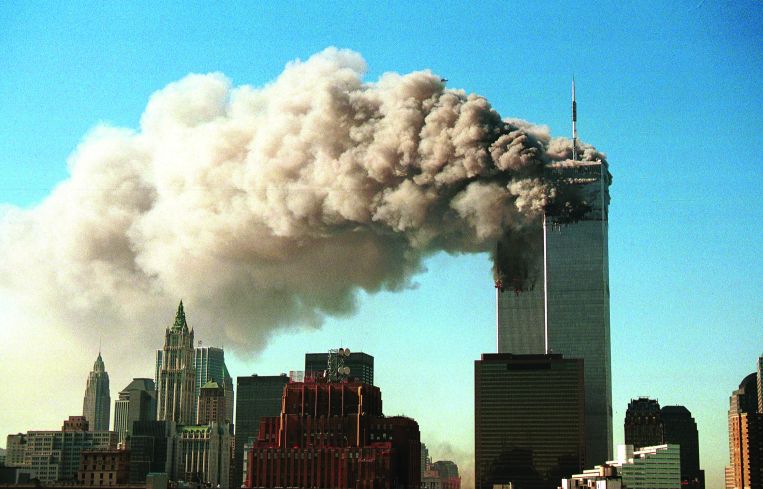

One Blue Sky Tuesday: The Real Estate Industry Looks Back on 9/11

How September 11 unfolded from the eyes of the top real estate people on the ground

By Cathy Cunningham September 7, 2021 9:00 am

reprints

Around 5 p.m. on 9/11, as the remnants of the World Trade Center burned, Mary Ann Tighe saw Larry Silverstein on Second Avenue, purely by chance.

“I began to cry, and Larry put his arms around me,” she recalled. “He said: ‘Sweetheart, we’re going to rebuild.’ That was the night of 9/11 and he was comforting me. That’s how strong he was.”

For Silverstein, rebuilding was the only option — even on the darkest of days.

“It quickly dawned on me that in not rebuilding, we would have let the terrorists win,” Silverstein told Commercial Observer. “They would have accomplished their mission, which was not just to destroy the Twin Towers. It was an attack on America, it was an attack on democracy, and it was an attack on our values and everything we’ve worked to create in this great country. So, to simply allow them to get away with that? No way.”

Still, the meeting is imprinted on Tighe’s memory, 20 years later. “I was a basket case, and this man — who had lost people on his staff, lost his investment, and didn’t know what lay ahead — was looking immediately to the positive. But, that’s Larry.”

A day like no other

The morning of 9/11, Silverstein was at home, getting ready to leave for work. Six weeks earlier, he’d signed a 99-year net lease on the Twin Towers. Since then, he’d spent every weekday morning having breakfast at Windows on the World on the North Tower’s 107th floor with one of his new tenants, getting to know them. He had the same plan that morning, until his wife reminded him of a dermatology appointment.

“I told her, ‘Sweetheart, I’ve got too much to do. Cancel it please.’” Klara Silverstein persisted, because her husband had canceled the appointment three times previously. “She got really upset. We were married for 45 years at that point, and when you’re married 45 years to the same woman and she gets upset, you can’t have that. So, I said, ‘OK, OK. Don’t get upset — I’ll go to the dermatologist.’ It saved my life in the end.”

Tighe was also home, at her apartment on York Avenue and 70th Street. A news report on the “Today Show” alerted her to what was unfolding as the first plane hit the North Tower at 8:46 a.m. She was on a high enough floor that she could look to the windows facing south and see the smoke with her own eyes. As she stared at the spectacle, the only words she could summon were: “Oh my god.”

Her first call was to her friend Cherrie Nanninga, director of real estate for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey at the time, and the woman who had facilitated the sale of the World Trade Center to Silverstein. Nanninga picked up immediately — she was safe.

Further downtown, Scott Rechler was in one of Reckson Associates Realty Corp.’s buildings on Park Avenue South. He was in the middle of a conference call when the first plane flew right by the window. “My colleague — who was a pilot — and I ran to the window, and I said, ‘Wow, that plane must be in trouble.’ He shook his head and said, ‘If it were in trouble, it’d be heading for the water.’”

They watched the plane fly down towards Lower Manhattan, and crash into the North Tower. “I remember falling to my knees, and clearly thinking: ‘We’re at war,’” Rechler said.

Carl Weisbrod, founding president of the Alliance for Downtown New York, was in his office at 120 Broadway. He was on the phone with then-Commissioner of Transportation Iris Weinshall when a colleague burst into his office and announced, “A plane has just gone into the World Trade Center.”

Back in 1945, a small plane flew into the Empire State Building, and Weisbrod initially believed that this plane could also somehow have lost its way — although, the clear blue sky that day gave him pause. When he went downstairs, 20 minutes later, he saw the second plane hit.

“I saw people jumping off the Trade Center,” he said. “It’s a day I’ll never forget.”

Weisbrod typically ate breakfast at Windows on the World three days a week. “I realized back then — but, especially now — how lucky I was, there but for the grace of God,” he said. “It’s only a matter of luck that I wasn’t there that day. Had I been, I would not be here today.”

Across the Hudson River in Jersey City, Tommy Craig and his team were working on constructing the Goldman Sachs Tower at 30 Hudson Street, which sat opposite the Twin Towers. On that sunny September day, Craig went for an early run along the esplanade, and by 8 a.m., his team was on the building’s fifth floor, erecting steel. An hour later, Craig was on the phone with his wife, watching in disbelief as the second plane hit the South Tower.

Later that day, Jersey City would become a triage site for people being evacuated out of Manhattan. “I spent my day trying to help in that regard,” Craig said. He eventually got on a train home to Connecticut at 9 p.m. from an unrecognizable Grand Central Terminal, which was almost completely in darkness and surrounded by armed police. “I was very grateful to finally stagger home to my wife and three young kids around 11 p.m.,” he said.

Are you there?

By the time the North Tower collapsed, the ability to communicate via phone or Blackberry had largely ceased. Rechler wanted to get back to the office to help coordinate whatever emergency protocols were going to be put in place, and began to walk uptown.

He remembers seeing people covered in ash, and the sound of F-15 fighter jets flying overhead. “Another thing that’s always struck me was that everyone was walking with phones to their ears, but no one had any service. There was just this desperation to connect with loved ones.”

As he walked, he stopped to look downtown to where the World Trade Center towers once stood, and saw a woman in the middle of the road, screaming for her father. “Two strangers were coddling her like she was their own daughter,” he said. “At that moment in time, l knew New York was one. It was one family, one community, and we were living this tragedy together.”

“That’s who New Yorkers are at their core,” Bruce Mosler said. “When the chips are down, New Yorkers are up — and that was visible that day. There was a helping hand all over the city.”

Mosler was driving back to New York from a business trip to Chicago that day. His colleague, John Santora, kept him apprised of the situation as it unfolded, and as he got closer to the city, he drove without stopping, keeping his eyes down. “As a New Yorker, I couldn’t bring myself to look downtown,” he said.

Santora had been part of the Cushman & Wakefield team that sold the World Trade Center to Silverstein. So, when the planes hit, he jumped on a subway downtown with seven of his colleagues to try to help.

“We couldn’t get all the way downtown, so we got out of the subway, and the first of the towers had already come down,” Santora recalls. “We came out to a storm of dust and debris and people running, but because we’d been stuck underground, we didn’t know what had happened. It took us a moment to get our bearings.”

A new dawn

While 9/11 was a day of tragedy, disbelief and shock, 9/12 marked a shift to a recovery mindset in New York City. Within the real estate industry, all hands were soon on deck, doing what they knew best.

“Everybody was scrambling,” Tighe remembers. “There were people saying we should put up Quonset huts on Long Island City to accommodate people going back to offices.”

Rechler found space at Reckson’s 919 Third Avenue for Sandler O’Neill + Partners, an investment banking firm (now Piper Sandler Companies), which had its headquarters on the 104th floor of the South Tower. Eighty-three Sandler employees came to work that Tuesday and 66 never returned home.

Later, Jimmy Dunne —the firm’s co-founder and CEO – wrote Rechler “a beautiful letter”, thanking him.

“If somebody had additional space or vacant space, it was offered with no fee in many instances,” Mosler said. “Our industry stepped up, and the level of professionalism and oneness made me very proud. The magnitude of losing 12 million square feet in one fell swoop was unheard of.”

Tighe was working at Edward S. Gordon Company at the time, and had placed several major tenants at the towers pre-9/11, including Marsh & McLennan Companies (now known as Marsh McLennan) and Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield.

On the day of the attacks, Marsh had 1,908 people working in, or visiting, its offices in the Twin Towers, of which 295 employees and 63 consultants perished. Empire lost nine of its 1,900 employees, and two consultants.

Tighe immediately went to Marsh’s Midtown office at 1166 Avenue of the Americas. “By that time, the second plane had hit and all hell broke loose, because nobody knew if there were more planes coming,” she said.

Over the days and weeks that followed, she busied herself with helping her clients. Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield soon operated out of hotel rooms in the W Hotel on Lexington Avenue, while Marsh’s employees moved to the company’s Midtown office.

“The question was, where were they going to go after that?” Tighe said, describing those days as “a period of enormous intensity.” In the end, Marsh moved to Hoboken, N.J., and Empire Blue Cross moved to Brooklyn.

Staying busy was a relief for Tighe, as it was for so many others: “It made you feel useful, because nobody knew quite what to do.”

On 9/12, Tighe’s brother, Tom Scarangello, a structural engineer with Thornton Tomasetti, started disaster recovery work on one of the most dangerous sites in U.S. history. Both siblings would ultimately play critical roles in the recovery and rebuilding.

Scarangello’s team, plus hundreds of others, worked at the site for the next nine months. Not wanting to waste time walking back and forth from his home in Union Square, Scarangello — and several others — slept and held meetings at PS 89, a nearby grammar school, for weeks.

“We, as fully grown men, would be sitting in these tiny kindergarten chairs, having meetings,” Scarangello said. In addition to securing the site and surrounding buildings, Scarangello and his team were organizing teams of engineers from across the country, ensuring the safe passage of rescue and recovery workers through the treacherous pile.

Scarangello also emphasizes the importance of feeling useful and staying busy. The enormity of what had happened hit him hardest when he finally walked home and saw posters of missing loved ones in Union Square Park. For weeks, New Yorkers lined the streets and cheered for the site workers.

Early on, the C&W team set up multiple operation centers in downtown bank buildings, working around the clock through emergency generators to keep banking clients up and running. They had to have diesel fuel delivered, with the Federal Bureau of Investigation escorting trucks to the properties. “We couldn’t let the bank operations stop,” Santora said.

Adrenaline played an important role. “You were blocking out what had happened,” Santora said. “You focused on helping any way you could, until there was a moment where your mind drifted, you’d look at the site, and tears would hit your eyes again.”

Morgan Stanley occupied floors 59 through 74 of 2 World Trade Center, and Hines was working on the construction of its new office complex at 745 Seventh Avenue. On the evening of 9/11, Craig contacted Frank Garigliano, Hines’ senior construction manager on the project, to ask if he thought they’d still have their weekly meeting with Morgan Stanley the following day. “He said, ‘Yes, I think you and I should go in.’ And, they did — as did every single team member working on the project from Morgan Stanley, Hines, Tishman Speyer, Turner Construction, Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates (KPF), Gensler and Jaros, Baum & Bolles (JB&B).

“To see all those people show up for Morgan Stanley, when they needed it most, was amazing,” Craig said.

The building received its temporary certificate of occupancy only 10 weeks later, and was sold to Lehman Brothers, which had 6,000 employees displaced from 3 World Financial Center and 800 from One World Trade Center.

On 9/13, Craig went to the site to try to help. Armed with his hard hat, vest and boots, he reached the site via motorboat, ferrying rescue workers from the New Jersey side. “It was a scene out of Armageddon,” he remembers.

One.

Sept. 11 showed us the worst of humanity, but also the very best.

“It brought, for a brief and fleeting moment, an extraordinary oneness,” Mosler said. “We had one individual who put this city on his back and, in many ways, the country on his back — and that was Larry Silverstein. He immediately said he was going to rebuild, and he kept his commitment to the city.”

Silverstein never expected it would take 20 years. “I told my wife, I thought we could get it done in 10 years,” he said. “Boy, was I ever wrong.”

Seven World Trade Center was the last building to fall on 9/11, and the first to be rebuilt.

Silverstein first secured its development rights in 1980. At the building’s topping-out ceremony in 1987, he remembers gazing up at the Twin Towers. “I said to myself, ‘Wouldn’t it be fantastic if I could own that someday?’” I couldn’t have dreamed that, one night in 1999, the governor would call me and ask if I had an interest in buying the Twin Towers. My immediate reaction was, ‘Yes.’”

Tower Seven was rebuilt on spec. Tighe secured its first tenant in 2006 — the New York Academy of Sciences, which leased space on its 40th floor. Moody’s Investors Service followed, but convincing other firms down to the site was often “painful,” Tighe remembers. “They’d say: ‘The number one terrorist target is the World Trade Center.’”

Other firms told Tighe they didn’t want to be pioneers. “I finally got my answer to that when Larry built the Four Seasons,” she said. “My answer was: ‘If you’re two blocks from a Four Seasons Hotel, you’re hardly a pioneer.’”

Eventually, a different set of WTC tenants than expected began emerging as the rebuilding progressed. “Nobody thought of Spotify,” Tighe said. “But it was fascinating to watch firms raise their hand.”

Tower Four was completed next, then Tower One, and then Tower Three. Five World Trade Center and 2 WTC are still underway.

“We’ve now spent somewhere in excess of $20 billion,” Silverstein said. “But there’s no comparison between what exists today and what was there.”

And while there’s now an appreciation for the courage and the force of will that Silverstein brought to the rebuild, “for 10 years, he was abused rather than appreciated,” Tighe said, describing the decade following 9/11 as a period of “hand-to-hand combat” for Silverstein. “It’s almost incomprehensible today, because everybody says, ‘Wow, look, what Larry did!’ Well, it only took 10 years for them to figure that out.”

The new WTC

Rebuilding on a site where so many had lost their lives was fraught with difficulties, and several stakeholders meant several different schools of thought.

There were also delays, although some were welcomed. Rechler— who oversaw the redevelopment of the World Trade Center as vice chairman of the Port Authority from 2011 until 2016 —recalled a moment of relief when construction had stalled on the 9/11 Memorial Museum. Superstorm Sandy hit, flooding the building up to the balcony. Had construction not stalled, hundreds of artifacts — kept elsewhere at that time — would have been destroyed.

“I always knew that there had to be a major memorial to the people who died there,” Weisbrod said. “But the commercial and business interests and the residents were united in the view that this shouldn’t just be a memorial — it should promote life as well as recognize the loss of life.”

Mosler sums the rebuild up in one word: pride. “There’s a tremendous sense of pride in how people came together, and in the leadership that was provided by so many who refused to simply lay down and say, “We’re going to mark this as a dark pit and not rebuild.” I think New York City became a beacon for the world in how you can respond in a crisis.”

Silverstein isn’t done yet. “I desperately want to get 2 World Trade finished,” he said. So important is this final accomplishment that, for his 90th birthday, he was presented with a cake in the shape of the building.

Sept. 11, 2001, changed our world forever. We’ll never forget those who perished, those who risked their lives to save others, and those who worked tirelessly on the recovery.

“On an anniversary like this, it’s important to talk about it, because it’s the only way that we keep the truth alive,” Scarangello said. “Maybe we can also remind people of a time when we were more united, and figure out how to get back to something like that.”

Cathy Cunningham can be reached at ccunningham@commercialobserver.com.

![Spanish-language social distancing safety sticker on a concrete footpath stating 'Espere aquí' [Wait here]](https://commercialobserver.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2026/02/footprints-RF-GettyImages-1291244648-WEB.jpg?quality=80&w=355&h=285&crop=1)