US Craft Breweries Retain Investment Allure Despite COVID

The pandemic closed dozens of breweries for good, but didn't kill the buzz surrounding the sector

By Tom Acitelli April 5, 2021 10:00 am

reprints

Craft beer swept out of Northern California in the 1970s, then across the rest of the U.S. in the next two decades. The number of smaller, independently owned breweries making beer with traditional ingredients and methods grew from fewer than 10 in 1980 to more than 1,500 in 2000.

A brief hiccup at the turn of the century — due to market saturation, a national recession and competition from such macro players as Anheuser-Busch InBev and Miller Brewing Co. — led to dozens of craft breweries closing.

In the next 20 years, though, the niche hospitality and retail sector made up the loss, and then some. By 2016, there were more breweries operating simultaneously in the U.S. than at probably any time in its history — nearly 4,200 — and most of them were craft, or microbrew, operations.

The sky seemed the limit, or the pint glass never looked near half-empty. Encomiums abounded about not only the individual craft brewery as a smashing business model — The Atlantic in 2018 declared craft beer “the strangest, happiest economic story in America” — but about the potential of the industry’s brewhouses, taprooms, and brewpubs to transform both city neighborhoods or out-of-the-way towns into hip tourist destinations.

“Their vintage shops and craft-beer bars generate jobs and taxes,” The Economist put it in 2015, describing urban hipsters. “So if you see a bearded intruder on a fixed-gear bike in your neighborhood, welcome him.”

The number of breweries in the U.S. soon ascended past 8,000, and then toward 8,500 as 2020 dawned. Then COVID hit, and craft beer seemed less of a sure thing.

Apocalyptic talk ensued. The Brewers Association, the main trade group representing craft brewers, released a survey in April 2020, where an overwhelming majority of responding breweries predicted they’d be out of business within a few months if governments did not lift various COVID-related business shutdowns.

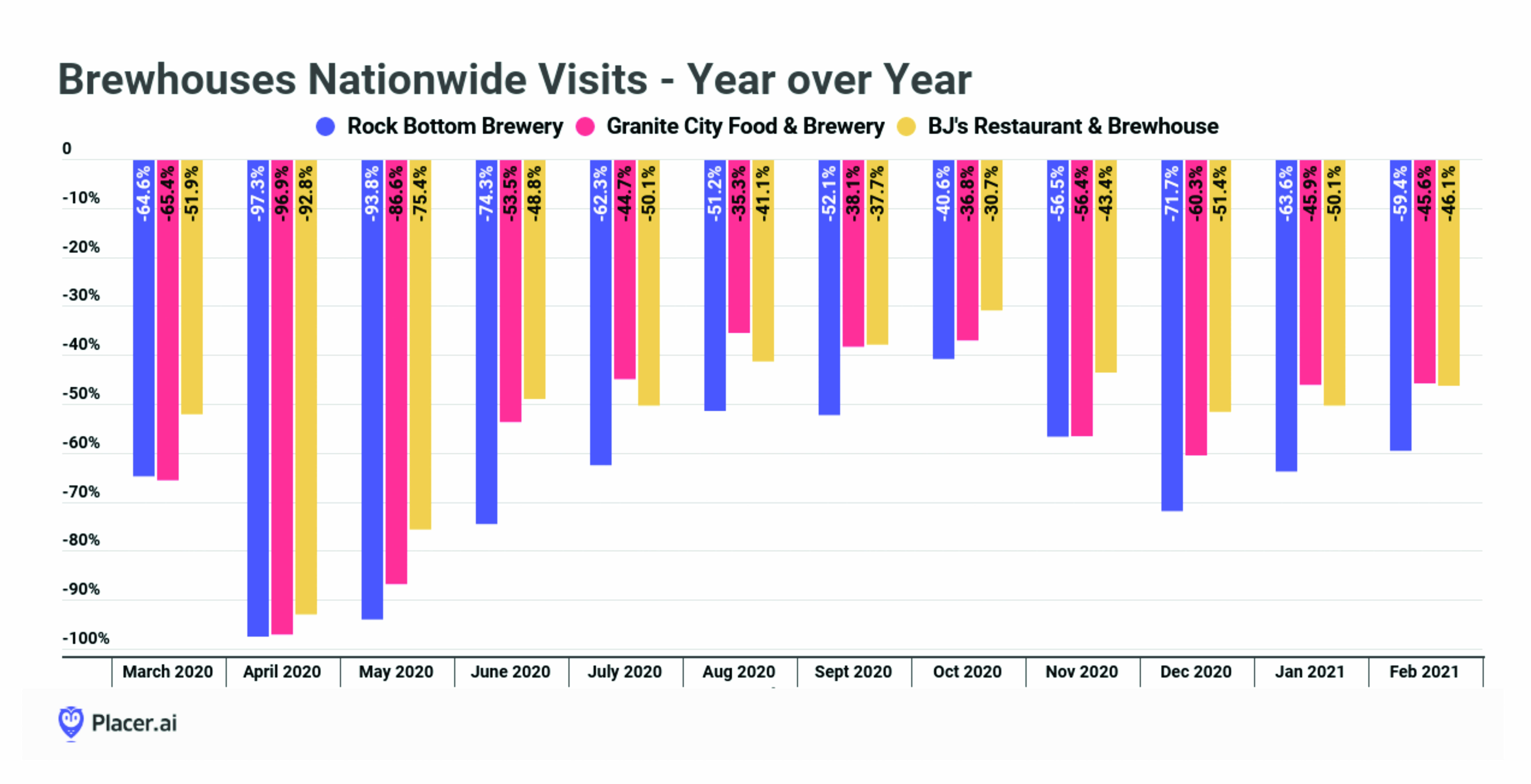

Much of the financial hit came from closed taprooms, those customer-facing hubs at the fronts of breweries where a lot of smaller operations do the majority of their sales. (Most craft breweries produce fewer than 1,000 barrels annually; the biggest operations, such as Sam Adams producer The Boston Beer Co., Sierra Nevada Brewing Co., and D.G. Yuengling & Son, turn out a few million each.) Sales of draught beer at craft breweries dropped nearly 100 percent by early April, according to the Brewers Association.

Yet, for all the ferment, the apocalypse never arrived. Craft beer production volume did drop an estimated 6 to 7 percent in 2020, according to the IWSR, a research firm on the alcoholic beverages industry. And hundreds of breweries did close, the Brewers Association estimates.

Still, craft beer and its breweries remain a stable, if bruised, part of America’s $116 billion-plus beer market. The numbers show it is desirable as an investment, and its prognosis shows it is likely a sound one, too.

Craft beer is also a bright spot compared with the — no question at all — bruised real estate worlds of hotels and brick-and-mortar retail. There has been tumult, but a lot of that predates the pandemic. That includes competition from fine wine, craft spirits, and, yes, a growing hard seltzer sector few saw coming, as well as the rapacity of the macro-brewers interested in acquiring micro market share.

For the most part, though, COVID will be remembered more as a scary time in craft brewing than a decisive one.

“Looking forward, we predict that the landscape of craft beer will return to being healthy in the next two years, with 2020 volume losses being balanced out in the coming years,” Adam Rogers, North American research director at the IWSR, said over email. “There will just be less breweries than there would have been pre-pandemic due to closures and reduced openings. We believe craft beer will return to growth of around 2 to 3 percent in 2021.”

This realization that craft brewing will indeed chug past COVID, however it has complicated the business, is informing both brewers and their financial backers.

Gage Siegel is the founder of Brooklyn-based Non Sequitur Beer Project. It was originally an operation that contracted its brewing out to other breweries with excess capacity, and then introduced its beers in temporary taprooms or at pop-up events around New York City. That events business dried up quickly once COVID hit, and Siegel said he realized that his company would need a physical taproom and brewery.

Drawing investors during the pandemic wasn’t easy, but it wasn’t that hard either, Siegel said. The number of craft breweries in New York City alone has grown from none in 1980 to dozens today, and Non Sequitur’s beers were already familiar via pre-COVID events. But Siegel still had to reckon with the pandemic when it came to investors.

“Nobody was willing to bet on that we’d be able to hit in-person growth numbers without waiting six, eight months and waiting on how COVID shakes out,” Siegel said.

In the end, though, the investment piled up. Non Sequitur plans to open a brewery and a taproom in one Bushwick location in May.

Such an outcome highlights the trends in craft beer at large.

Mainvest, an investment and crowdfunding portal, reported upticks in 2020 in both breweries seeking investment and investors responding. There was a fourfold increase during the first 12 months of the pandemic in the investment campaigns that breweries launched versus the 12 months right before COVID, as well as a 250 percent increase between the two periods in the number of investments made in craft breweries. Also, the total investment in those craft brewery campaigns increased 350 percent during COVID, according to Mainvest data provided to Commercial Observer.

Craft breweries have long drawn such investment, making its continuance not all that surprising. Individual entrepreneurs started the original craft breweries, usually with money from family and friends. The model became a little more sophisticated in the mid-1980s, when a management consultant with Wall Street connections named Jim Koch and a software engineer with Silicon Valley connections named Pete Slosberg started dueling brewing companies, Boston Beer and Pete’s Brewing (readers of a certain vintage will remember Pete’s Wicked Ale).

By the 1990s, investment in production as well as brick-and-mortar breweries, brewpubs (breweries that serve their fare on-site with food), and taprooms for sampling myriad concoctions diversified significantly.

Mammoth operations, especially Anheuser-Busch, bought stakes in individual craft concerns, and craft brewers sometimes teamed with each other to form larger brewing companies and wider distribution channels. Some brewpubs, too, grew into regional or national chains.

Private equity and venture capital also jumped in, a trend that only accelerated in the new century. Venture capital firms’ total investment in U.S. craft brewing companies went from $2.2 million off six deals in 2010 to $49.5 million off 59 deals in 2015, to $73.4 million off 36 deals in 2020, according to research portal PitchBook. The sum peaked annually in 2019, at $83.2 million off 36 deals.

The VC investment seems, if anything, steady amid COVID. As of March 26, the total VC investment in craft brewing in 2021 was $45.7 million off 13 deals — more than half the peak total in 2019 from one-third the deals.

The numbers are less dramatic in private equity alone, according to PitchBook. They still show that investment has not really careened due to COVID. There was $4.1 million in private equity investment in craft brewing in 2020 versus $3.6 million in 2019. The decade-long peak was in 2016, when a series of big deals, including a $120 million acquisition and leveraged buyout of Pennsylvania’s Victory Brewing and $90 million for expanding Southern California’s Stone Brewing, drove the private equity investment for that year to more than $281 million.

Meanwhile, the macro-brewers moved on from just stakes to acquiring whole craft operations.

Budweiser-maker Anheuser-Busch InBev — the company that itself came about due to a merger in 2008 — has purchased at least 15 craft breweries in the past decade. The 10-year anniversary of its purchase of Chicago’s Goose Island, which kicked off the biggest wave of macro acquisitions of micros, just passed in late March. In September 2020, AB InBev acquired for about $220 million full control of what was called the Craft Brew Alliance, which included seven craft beer brands that had partnered and which traded on the Nasdaq.

That was another investment avenue — stock exchanges — that craft brewers pursued, beginning with a wave of initial public offerings in 1995 and 1996. These included Boston Beer, which still trades on the New York Stock Exchange, as well as the now defunct Pete’s Brewing. The Boston Beer stock — trading under the ticker SAM and including the Dogfish Head beer, Angry Orchard hard cider, Twisted Tea hard iced tea, and Truly Hard hard seltzer brands — went from under $400 a share at the pandemic’s start to nearly $1,200 a year later.

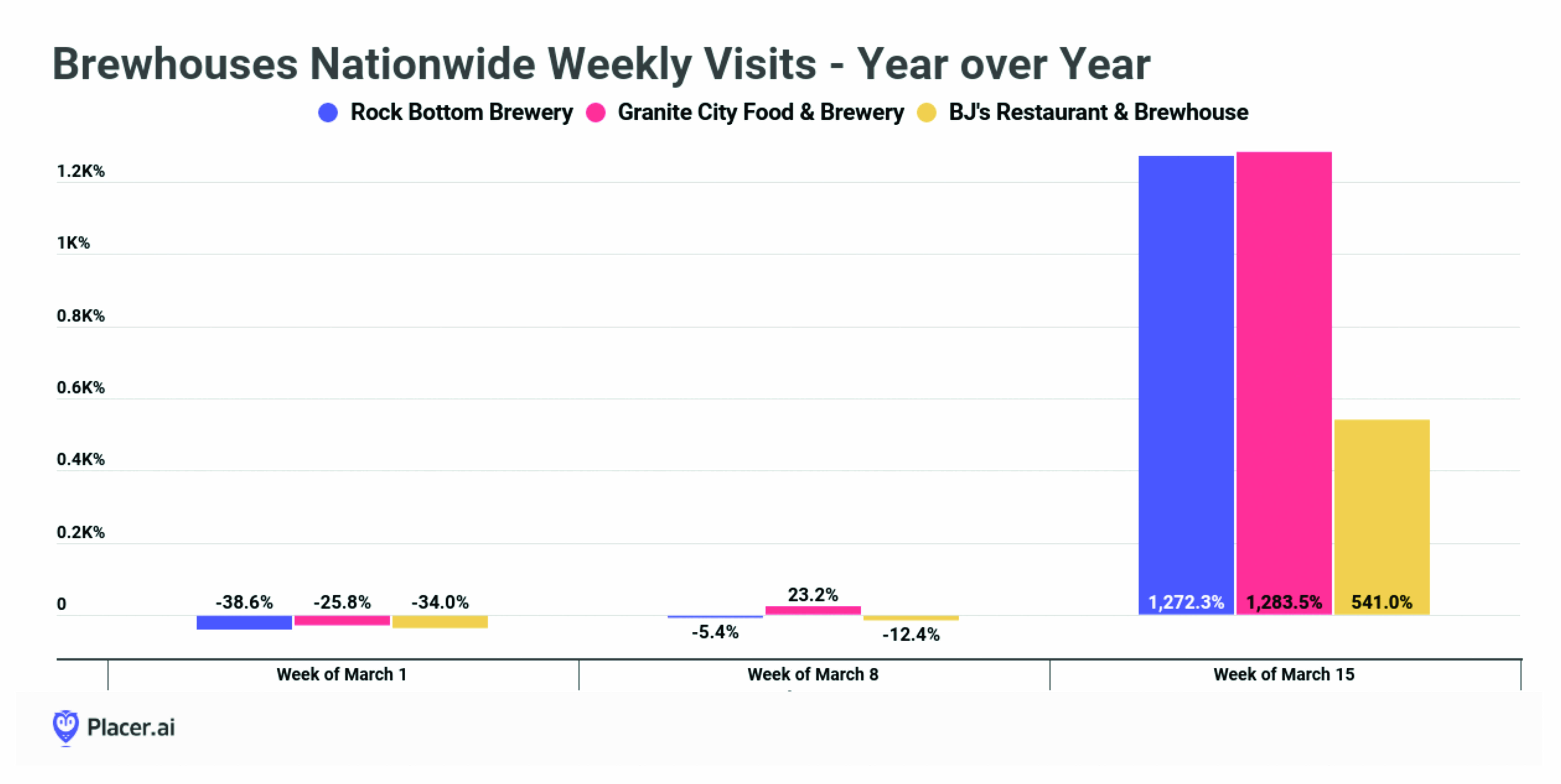

As taprooms and brewpubs reopen behind the rollout of COVID vaccines, such financial performances in craft brewing are expected to continue. The sector will make up the ground it lost during the pandemic, and that lost ground might not prove as expansive as originally thought.

The Brewers Association estimates that between 300 and 350 breweries closed in 2020. But it also estimates that more than 700 opened. Also, the number of 2020 closings is similar to the number in 2019.

And, while the number of openings is down an estimated 25 to 30 percent from 2019, one-half to two-thirds of that 2020 decline was seen coming even before COVID, according to Bart Watson, the association’s chief economist. That was due to the competition from macro-brewers, vendors of other alcohol like craft spirits, and just the general competition that comes from a marketplace adding several thousand producers in a few years.

Craft beer is still expected to grow at least through the early part of this decade, according to an analysis released in April 2020 by consumer research firm IBISWorld. It might be considerably less growth than in the previous decade — maybe 2.1 percent revenue growth on an annualized basis to 2025 — but “the industry may still be several years away from experiencing a plateau in annual growth.”

The popularity of craft beer, then, has sustained it through COVID’s lockdowns and distribution disruptions, something brewers are feeling firsthand. Gage Siegel said that when he was trying to raise funds for his Non Sequitur Brewing during the pandemic, people comprehended the potential right away, whatever the collapsing world all around.

“They at least understood, hey, I’m basing these numbers on things that are very much attainable if people start going back out,” he said.