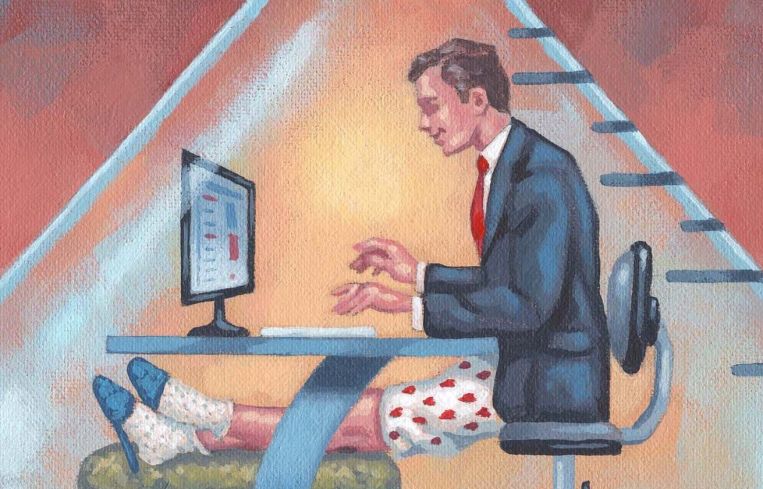

Do We Need Offices? Coronavirus Provides a Wide-Scale Work-From-Home Experiment

Companies forced to switch entirely to working from home because of coronavirus have provided a large-scale case study for remote work. Experts think it will reshape the way companies see offices in the future.

By Nicholas Rizzi March 26, 2020 7:30 am

reprints

Crises beget innovation. Canned food was invented as a way for Napoleon to feed his troops. Digital photography was originally a way to spy on the Russians.

In 20 years, our children might say, “People used to work in offices before the Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020.”

Whether that’s the case or not, a large-scale global experiment is underway concerning just how effective work-from-home is — and how necessary offices are.

“I have no doubt that the office will be reshaped,” said Tom Vecchione, a principal at architect and interior design firm Vocon. “Major crises make us rethink and replan what the normal was before and what the new normal needs to be.”

“We will think very differently about how we group up, how we meet, how we gather and how we create work and review work,” Vecchione added.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo ordered last week that 100 percent of nonessential workers in New York State remain home. Companies in New York City had previously closed their offices before the announcement, some after employees tested positive for COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. Employees at Brookfield Properties, Meridian Capital Group and members of WeWork and Convene were found to have COVID-19.

The pandemic has had a severe global economic impact as many businesses have had to essentially pause their operations or shutter — with thousands of workers laid off. But for the ones still operating, the health crisis has forcibly provided the largest case study of working from home in history.

“This is a research goldmine,” said Barbara Larson, a professor of management at Northeastern University who has studied remote work for years.

While there have been previous studies on the benefits and drawbacks of remote work, they have only targeted a handful of companies at a time and mostly ones that require a minimal level of supervision and collaboration, Larson said. Now, researchers will be able to see the impact on a vast number of corporations in multiple different countries and industries.

“What we don’t know yet is what happens in terms of productivity for jobs that require considerably higher levels of collaboration,” she said. “We have lots of reasons to believe collaboration can occur in a remote setting, but the practices to enable that are still pretty undeveloped and they’re very understudied.”

Aside from the research potential, the global work-from-home experiment could have an impact on companies’ office space in the future. If employers see that it’s more or less business as usual, it could make them rethink their remote work policies, leading some to take less office space or even have no physical presence at all whenever the world returns to some level of normalcy.

“For each different type of business, folks are going to see how effectively their business can be done without being able to be in an office,” said Bob Knakal, the chairman of JLL’s New York investment sales. “This experiment could confirm traditional perceptions about the collaborative benefits of being in an office together or may change those perceptions for certain businesses or parts of certain businesses.”

“Each business will have to take a look back, after the experiment is over, and make a determination as to what the most effective way to deliver their service or product is and make office space decisions based upon what they have experienced, what they think is best for their business and, importantly, what is best for their clients and customers,” Knakal added.

Eugene Lee, the COO of flexible workspace provider Knotel, said the pandemic will make working from home “a permanent part of how we do business” whenever people can return to offices.

“I would expect when we’re on the other side of this that many companies will realize there are different models of working,” Lee said. “The general trends are that having people show up in the same office and having these massive footprints is going to be proven that that’s not the only way we have to do business.”

Landlords could be on the hook to find more tenants in their properties if that’s the case, but Lee said it’s exactly what Knotel has planned for with its model of leasing space from owners then offering mid-level companies flexible deals. (Amidst the coronavirus epidemic, the company has pivoted to trying to partner with the government to offer up its now-mostly-empty portfolio for emergency needs.)

“This is the definition of what Knotel was built for,” he said. “I think flexibility is going to be something that is valuable to people right now.”

But not everybody’s convinced companies will start ditching their offices en masse to let employees work on their couch after the pandemic wanes. James Wacht, the president of brokerage Lee & Associates NYC, said he can’t wait until his company can get back to the office.

“I’m a big believer that proximity creates opportunities and if you lose that — employees not meeting each other — it’s just a lot less communication going on,” Wacht said. “Lack of communication, at least in our business where information is very important, is a big negative. My expectation is we’re not going to change how we conduct business as a result of this.”

But even before the coronavirus pandemic forced companies to adopt work-from-home policies, the practice has had a large surge in recent years thanks to the increase of home internet speeds and the adoption of software like Slack and Zoom that makes it easier for teams to stay in touch from anywhere in the world.

A 2019 study by the Society for Human Resources Management found that 69 percent of organizations in the United State now give employees the option to work from home, a 13 percent increase from 2015. The study also found that 27 percent of companies allow workers to work remotely full-time. And there’s evidence to show that’s a good thing for employers.

Stanford University researcher Nicholas Bloom studied a 16,000-employee Chinese travel agency that allowed call center employees to work from home over a nine-month period. Bloom’s findings showed a 13 percent performance increase from those allowed to work remotely while the company’s attrition rate halved.

“The reasons for that appeared to be they were actually working more,” Larson said, adding that one cause for the increase in productivity was employees spent less time commuting to and from work.

She also said employees were able to create a workspace tailored specifically to how they like to work instead of being forced to adapt to office life.

“[Instead of] working in cubicles in a very large customer service center, they were able to create a workspace within their homes that were more customized to their needs,” Larson said. “Having the ability to create a comfortable workspace was a benefit.”

Bloom’s study also found that the number of sick days employees took decreased because they were more likely to work their shift if they were “on the edge” of being sick instead of calling out the entire day, Larson said. And other studies have shown evidence that working from home leads to decreases in conflicts with family over the number of times employees spend working, according to Larson.

One of the keys to successfully switching to remote work is putting in place policies to help the transition — something many companies didn’t have the time to do because of the coronavirus, Larson said. The best companies allowing working from home sometimes require employees to have a dedicated desk to work at or provide child or elder care so they’re less distracted tending to their families.

“The really well-run companies — this is only a fraction of all companies that allow remote work — will actually provide training for remote work,” Larson said. “The truly excellent companies will also train for the more social and psychological aspects of remote work.”

But while productivity does increase when employees work remotely, there can be a sense of isolation some workers feel because they’re not talking with coworkers or their supervisors, Larson said.

“If you talk to employees working from home, one of their biggest concerns is that they’re not getting as much communication,” she said. “They feel like they just disappear when they go home.”

Larson gives companies tips to increase social interaction by suggesting they start video conference meetings early to give people time to chat about not strictly work topics and host virtual happy hours or pizza parties. Knotel has practiced similar tactics after the coronavirus forced them to move their corporate workforce completely to remote; CEO Amol Sarva hosted a virtual St. Patrick’s Day Party, Lee said.

There have been some public failures in remote work even as the practice becomes more widespread. Former Yahoo! CEO Marissa Mayer made waves in 2013 when she called the technology company’s then-11,500 employees entirely back into the office, The Guardian reported. Bank of America, Aetna and IBM have also cut back or banned telecommuting, NBC News reported.

And in this instance, the coronavirus forcibly created this work-from-home experiment, giving companies little time to get the best practices in place. Employees are also dealing with anxiety about the dangers of the pandemic, unable to leave their homes much and in many instances forced to handle childcare themselves during work hours—this particular experiment might give employers a bad idea on what remote work is like under normal circumstances, Larson said.

“I do think, very strongly, if companies take the next two months as indicative of what it’s like to have employees working remotely, they risk drawing some bad conclusions,” Larson said. “It’s not at all a typical remote work situation.”

Vecchione said Vocon had some work-from-home policy in place beforehand, but it wasn’t as robust as what’s needed now to get things done while the entire 70-person New York office switches to telecommuting.

“The hardest thing is mentorship and communication,” Vecchione said. “I found that we’re spending a lot of time structuring communication.”

Knotel has always been open to the idea of telecommuting for its corporate workers — with many working remotely before the pandemic — but switching the entire company to the model has had some drawbacks, Lee said.

“In spite of the best tools and systems you have, a personal live interaction is maybe the quickest way to deal with some complicated issue,” Lee said.

However, both Vecchione and Lee have seen some advantages to the switch, with meetings at Knotel running swifter than before.

“Lots of people waste lots of time in meetings and one of the interesting things about working remotely is people become more efficient and more focused,” he said. “Nobody wants to be on a video call longer than they need to be.”

And with more independence in employees’ work-life, Vecchione said, Vocon’s became a more accountable organization.

“People have started to take a lot more ownership of their independent work,” he said. “Everyone realized that they have to be so overly accountable and get things done.”

Regardless of the impression employers get about remote work during these times, many believe the coronavirus will have a major impact on the future of office space to come.

“The design of the workplace in three months or six months or nine months — we’re not going back,” Knotel’s Sarva said. “It will not be back to two years ago. The workplace will be different, density is going to change. Hygiene and cleaning and operations are going to change, even build-outs will change.”

One casualty could be the open floor plan offices companies have embraced in the past decade, Vecchione said. The Wall Street Journal reported this month that the model is basically a petri dish, ready to spread diseases like COVID-19, and Vecchione has already talked to clients rethinking them.

“[Companies are looking] how to create a healthy workspace versus just a well-run workplace,” Vecchione said. “Clients have expressed concerns about over-occupancy and what are some safeguards we could put in so that we make for a healthy, sustainable environment.”

A source who did not want to be named said the rethinking of open floor plans could wreak havoc on an already struggling coworking sector, since people will be wary of packing together in tight confines with strangers after this.

An increase in working from home can allow companies to move away from the open floor plan model easily. Corporations can reduce footprints and offer “hot desks” where employers stopping in the office simply claim a desk for a day, Larson said.

Aside from saving money on real estate costs, it can let companies become greener as they use less energy in offices and have fewer people driving into work.

“I think another reason employers are considering [allowing more telecommuting] is the [positive] environmental impact you have,” Larson said. “You can lower the carbon footprint of a company.”