Getting Started: REBNY Paves Way for Career in Construction

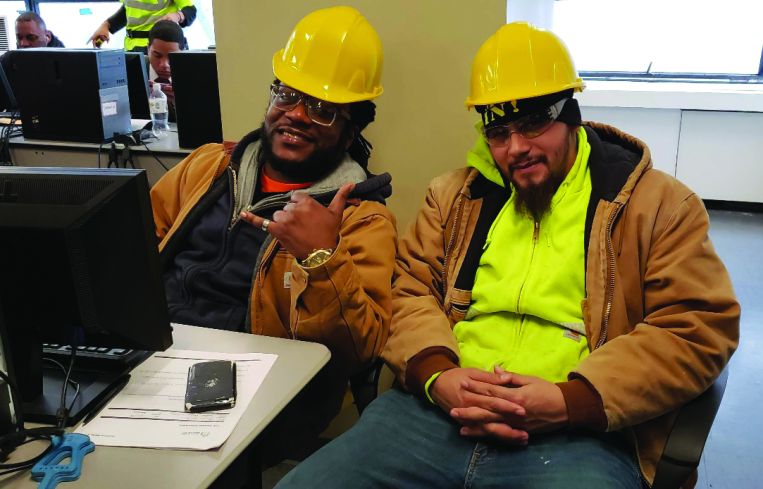

Building Skills NY is a workforce development group supported by REBNY that specializes in training unemployed for construction jobs.

By Aaron Short February 1, 2020 3:00 pm

reprints

For New Yorkers who want a career in construction but don’t know how to get started, the industry can look intimidating, complex and opaque, to say the least.

How do you know if you have the proper training or even the right tool set? How can you get a gig at Hudson Yards or any of scores of construction sites across the city? Do you have to know a guy?

Increasingly, the “guys to know” are Building Skills NY, a small but plugged-in workforce development group supported by the Real Estate Board of New York with a four-year track record of training and placing hundreds of unemployed and under-employed workers in the industry.

Building Skills NY’s Executive Director David Meade came to the nonprofit in 2017 after running the Southwest Brooklyn Industrial Development Corporation for seven years and found an organization with the potential to grow and deeply affect people’s lives. After placing 125 people in construction jobs in his first year, he’s nearly tripled that figure to 340 last year, in over 50 active sites.

Meade credits REBNY with much of the group’s success.

“Their investment — they provide space for recruitment, for trainings — that’s huge,” Meade told Commercial Observer. “They connect us to some of their members who are doing these projects through the city who connect us to construction [leaders] or a construction project manager. We go in and talk with them, think about how we can find some great entry-level candidates who can learn a trade and go work from there.”

Building Skills relies on about five dozen nonprofit partners to refer people from underserved communities in their networks who want to explore a career in the building trades.

Nearly all the workers, about 97 percent, are people of color and about 10 percent are women. Meade hopes that even more women candidates realize there are enticing opportunities in an industry where the labor market has tightened in recent years.

“We see a lot of amazing female candidates who want to get their foot in the door,” he said. “Contractors we work with are interested in them and we want to see that rate get better and better.”

The first step is to ensure prospective workers have the proper safety training — 30 hours as of December 2019 — before stepping onto a construction site.

Once individuals are OSHA certified, workers attend a group recruitment session on Monday or Tuesday mornings at 6:30 a.m. sharp at REBNY’s midtown office space where Building Skills staffers determine what kind of construction positions they want before placing them at a site. A building services manager from the group accompanies recruits to the location and helps them map out the construction site so they know where they’re going once they’re on the property.

“They’re a little anxious on their first day but there’s a lot of moving parts and logistical hurdles at a new construction site and we want to make sure they have success from the get-go,” Meade said. “We stay with the individual that first week and check in to see how they’re doing.”

Construction managers have the expectation that they’re coming into a job with a toolbox or at least have experience knowing how to use everything. But for those who are starting in the industry, Building Skills will work with nonprofit providers to purchase helmets, boots, and the cost of a Metrocard until they start earning paychecks.

The average gig lasts four to five months, while some can last as long as two years. When the job is finished, workers come back through the program and get placed somewhere else.

Roughly four out of five participants work three months or longer on the site, making repeat visits common.

If a subcontractor doesn’t hire the construction worker on a more permanent basis, Meade and his colleagues connect the person to other jobs while also engaging with them over long-term career goals such as becoming a plumber, carpenter or electrician.

“Hopefully we’re building on some of the experience they got on that last job and we’ve gotten a sense of what skills they learned, what interests they have, and whether we want to move the person from general labor to a trade,” Meade said. “They have a sense of where they’d like to go. We do our best to help facilitate the next step for them.”

Moving to a trade can mean a significant bump in pay. General laborers earn starting wages at $16.50 an hour, a tick above minimum wage, for lifting and loading heavy objects, making deliveries, removing debris, or flagging traffic for eight hours a day. More specialized work like being a junior mechanic, plumber helper, a mason, or a carpenter can command in the $20- to $30-per-hour range.

Without these jobs, workers might be stuck in a retail, landscaping or warehouse loading positions.

“We are paying more than retail and certainly more than minimum wage. Economically, construction can be a better opportunity,” Meade said. “We have a large pipeline of jobs and we’ve been searching desperately to fill positions. There are a lot of really good people on the bench who are looking for work.”