How Les Wexner Created the Richest Town in Ohio

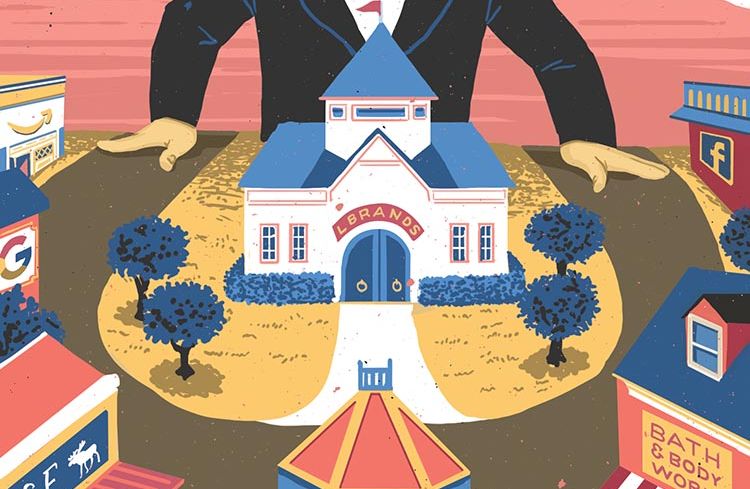

Les Wexner, founder of L Brands, created the richest town in Ohio, with tax incentives designed to make tech companies like Amazon, Facebook, and Google swoon.

By Chava Gourarie November 19, 2019 10:30 am

reprints

Discovery is tied up in the name “Columbus” — so, perhaps, Columbus, Ohio-native Leslie Wexner took that spirit to heart when he set out to discover a land of his own.

In the 1980s, Wexner, a billionaire retail magnate and magnanimous philanthropist, went looking for a place to build an estate — or a fiefdom, really — and his eye fell upon the humble townlet of New Albany, 20 minutes northeast of Columbus. And lo, Wexner bought a plot of land in the Central Ohio village of 485 people.

Then he turned it into the state’s richest enclave.

New Albany now has a population of 10,700 and its boundaries have ballooned, crossing county lines, biting off pieces of nearby townships, and roping in others to help manage roads, schools, and infrastructure. It has a median income of $215,000, quadruple the state’s median income of $54,000, according to 2017 data, and homes sell for an average of half a million dollars.

The town is carefully designed to resemble a 19th century ideal of small-town America. World-renowned architects were hired to design blocks of genteel Georgian homes, green lawns and a charming Main Street, surrounded by landscaped acres of parkland, bike paths and unspoiled nature. “Nothing is left to chance,” the city’s website assures its visitors. It draws comparisons to Shaker Heights, a suburban Cleveland community that was planned in meticulous detail by a pair of railroad titans in the early 1900s.

Wexner, founder of L Brands — parent company to Victoria’s Secret and Bath & Body Works, among others — is a household name in Ohio, and certainly in Columbus, where his moniker is plastered across hospitals and schools and museums. His is a rags-to-riches story: the son of Holocaust survivors who built a single store into a retail empire. He was and remains — now in his eighties — one of the city’s primary power brokers, and one of its richest men.

Wexner’s home in New Albany is a 60,000-square-foot castle so large and secluded it inspired a raft of media coverage and speculation; so Gatsbian it has an elevator that drops the dining room table into the kitchen, to be set by the staff, and then elevated back to the dining room, according to someone who’s seen it; so excessive it took 20 companies to build it and a team of off-duty policemen to guard it, per a Columbus Monthly article from 1990.

When he moved, people referred to New Albany as “Wexley” — a play not just on his name but on Bexley, the wealthy Columbus suburb where he previously lived.

His neighbors and business partners and friends built estates and houses too. Some of them even moved their business headquarters as well. They joined boards and committees and foundations and associations, and the town began to take shape.

“The whole master-planned community is the way it is because Les Wexner chose it to be,” said one happy resident, a father and business owner who moved from Los Angeles 10 years ago. “He’s the Godfather.”

In recent months, Les Wexner and his town gained national attention, but not the kind he was looking for.

He was close friends with the notorious financier and sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, who was arrested on sex trafficking charges this summer and later found dead in his prison cell. Epstein was widely known as an influential financier, who hobnobbed among celebrities, politicians, princes and Harvard academics, but his only known client was Wexner himself.

After Wexner met Epstein in the late eighties, he hired the teacher-turned-moneyman to manage his finances, and by 1991 had granted him power-of-attorney over his wealth, businesses and properties, according to county records. Their relationship continued through the nineties, and Epstein owned a house on Wexner’s New Albany estate, as well as an Upper East Side mansion that had previously belonged to Wexner, and both locations were implicated in Epstein’s crimes.

Wexner cut ties with Epstein in 2007, when the latter came under investigation in Florida for sexual misconduct with minors. Wexner has claimed no knowledge of Epstein’s criminal actions, and in a September call with L Brands investors, Wexner said he had been betrayed by Epstein.

“Being taken advantage of by someone who was so sick, so cunning, so depraved, is something that I’m embarrassed that I was even close to,” he said.

But Epstein played an important role in the formation of New Albany itself. In 1998, Wexner founded the New Albany Company to manage his real estate holdings there, and it was Epstein who signed the incorporation documents as president of the company, alongside Wexner, according to state records.

And the New Albany Company would be pivotal in shaping Wexner’s Midwest Eden.

Before Wexner moved to town, the plains around New Albany bore a palette of tilled farmland, grassy fields, and clusters of woods veined by narrow roads. Now, the landscape retains its low Midwestern horizon, but instead of beans and corn, the cash-crop filling its flatlands is of a binary kind.

The Columbus exurb has become a business powerhouse, a sprawling network of corporate campuses and a center for the most cutting-edge manufacturing, logistics and data facilities, that has successfully wooed Google, Facebook, and Amazon to set up shop within its borders.

That, of course, is by design. Early on, the New Albany Company (now chaired by Wexner and Jack Kessler) set aside land for a corporate park that would help create a commercial tax base for a growing city.

Today, the 4,500-acre International Business Park stretches nearly seven miles along Route 161, a state highway that arches over Columbus like an eyebrow, and cuts through the town of New Albany. The campus is headquarters to national brands like Abercrombie & Fitch and Bath & Body Works, home to Fortune 500 companies like Discover and Aetna, and a base for data titans. It’s helps pump $4 billion of private investment into the city annually.

Much of the commercial real estate was built with government subsidies; a tangled network of state economic development incentives, local job creation programs, and municipal tax abatement schemes. Its success also rested on the hearty approval of the city’s residents, creators, landlords, and administrators — some of whom are all four.

One can be forgiven for conflating the town and the company; the New Albany Company is the city’s largest landowner by an enormous margin, and consequential decisions are made by a public-private partnership between the two.

“The City of New Albany has a proven track record of working in partnership and collaboration with the private sector to support economic development activities,” Scott McAfee, the city’s public information officer, wrote in an email. “Our mantra is that we work at the speed of business not the speed of government.” (The New Albany Company directed inquiries regarding this story to the city of New Albany.)

It’s quite the track record.

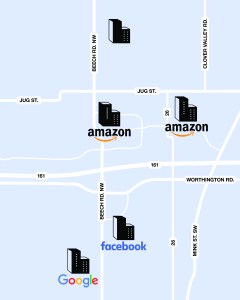

Along Beech Road, which runs north-to-south through the eastern part of the International Business Park, three of the world’s biggest tech companies — Facebook, Google and Amazon — are all building data centers. They are not the only data centers in town but attracting the titans of tech was part of a concerted strategy on New Albany’s part.

“Largest internet company; largest social media company; largest search engine,” said Doug Godard, a broker with CBRE and data center expert, who helped negotiate the deals for each of the companies. “Now that you get the three largest hyper-scalers in New Albany, they’ve already proven that area.”

The effort to entice cloud companies to New Albany began over a decade ago, long before the data center industry matured into what it is today.

“One interesting opportunity for the Village of New Albany is the attraction of ‘data centers’ for national and international firms,” the city’s 2006 strategic plan states. The report points out that data centers require up to 15 times more energy than traditional office or industrial use, and that the city would need to invest in infrastructure, such as a fiber optic network, in order to be competitive.

That same year, the American Electric Power Company (AEP), which supplies electricity to 1.5 million people in Ohio, announced that it would move the headquarters of its Transmission arm from Columbus to New Albany, to be built on land then owned by the New Albany Company. Its new location, completed in 2008 and expanded in 2014, provided the infrastructure necessary to fuel the energy-hungry data centers.

The strategy paid off. The first data center was approved in 2008, and the city now has nine, according to McAfee, and is actively seeking out additional companies to locate there.

“New Albany markets to information technology operations and businesses that compliment data hubs, including call centers and corporate offices that could be tied to those data centers,” said McAfee. “We also invest in traditional and technology infrastructure to help support these kinds of operations.”

In addition to the existing infrastructure, and a highly eager economic development team, New Albany has a few other advantages: It is ideally located to serve the highly populous coastal cities, land costs are relatively low, and its proximity to Columbus provides a highly-skilled labor pool. “Columbus is right in the heart of the golden triangle, between New York, D.C. and Chicago,” said Godard, which means it can offer better load times to two thirds of the country’s population.

“The city of New Albany and New Albany Company are working hand-in-hand to prepare hundreds of other acres for the next phase of data centers,” said Godard. The city’s economic development team works closely with AEP, and sends teams to pitch companies nationally, he said.

Starting at Beech Road near its intersection with Morse Road, the southern border of New Albany, on one side Google is building a $600 million data center, while on the other Facebook has nearly completed a 1.4-million-square-foot complex. (A cheery Facebook page dedicated to the site posted a holiday message from “your friendly neighborhood data center” last December.)

“When we started our site selection process, we met with local organizations like Jobs Ohio, Columbus 2020, The New Albany Company, and the City of New Albany,” a spokesperson for Facebook said. “Their diligence and professionalism were a critical part of our decision.” The spokesperson also cited the infrastructure and talent pool as reasons for locating there. (Google and Amazon declined to confirm details or comment for this story.)

Google broke ground on its campus earlier this month, simultaneously announcing a long-term supply agreement deal with AEP for 100 percent renewable energy. The campus is located next door to Doran’s Farm Market, a family-owned farm and shop that’s been around for decades. “The building’s pretty much up,” said a woman who worked at the shop who declined to give her name. “We can look out our back door and we can see it.”

Moving further north on Beech road, on one side is the Personal Care and Beauty Campus, an experimental endeavor that brings the entire beauty supply chain into one geographic area to streamline beauty logistics, designed for Bath & Body Works, but utilized by other companies as well. Immediately north is a three-building Amazon complex. As of this month, the city has approved an expansion of the Amazon campus, with another $400 million data center planned on a 100-acre site.

And finally, moving across Jug Street, New Albany annexed and rezoned 484 acres earlier this year, and the land is being marketed as data center-ready.

In every one of these cases, the land underneath the data centers belonged or belongs to the New Albany Company, through its subsidiary MBJ Holdings. The parcels sold to the three tech companies netted the company $99.5 million: Amazon paid $12 million for its 68 acres, Facebook paid $70 million for 600 acres in two separate deals, and Google paid $27 million for 225 acres.

MBJ owns the land under Amazon’s planned new site, as well as a 145-acre site on the annexed land north of Jug Street. The annexation was done at the request of the New Albany Company, as was the rezoning of the land from agricultural use to a limited-employment district, which allows for a range of commercial and industrial uses.

Each of the deals is approved by the city council and comes with a package of state and local tax benefits. While the resolutions all pass without a problem, the reaction from some local residents is documented in pages of city council minutes, with complaints about traffic, air quality, and noise.

“You have taken away all of the nature; no blue sky, no stars, no frogs, no crickets,” said Erin Myers at a planning commission meeting in 2018. She lives on Beech Road and hears Amazon’s gates beep every 15 minutes as security makes its nightly rounds.

There’s no doubt that all this economic development has brought tremendous wealth to the region as well as to the landowners, but it’s not always clear at what cost. Or, perhaps more critically, at whose.

All three tech giants received tax subsidies from the state in exchange for somewhere between 50 and 100 jobs apiece, and all of them received, at a minimum, 15-year local tax property abatements in exchange for promised income taxes. Amazon was approved for utility discounts whose cost could be passed to residential owners. And the opacity of many of the deals makes it difficult to parse their exact value.

“It’s kind of ironic that these data centers are going into New Albany which is one of the wealthiest communities,” said Zach Schiller, a researcher at Policy Matters Ohio.

Nationally, there is a debate over the benefit of data centers to the communities they settle in. “What we’re finding is more communities wanting to recruit these,” said Pat Lynch, the head of CBRE’s data center team. “These are very expensive assets, they create a nice construction base, and on a long-term basis, they create extensive fiber networks. It’s true they don’t employ a lot of people, they also don’t put cars on the road.”

On the other hand, data companies often negotiate lucrative state and local subsidies and the communities see no benefit. Google, Amazon and Facebook have all reportedly used nondisclosure agreements and other techniques to keep their negotiations under wraps until it was too late for affected communities to intervene.

Ohio is one of the many states to offer generous tax exemptions for data facilities, providing a data-center specific tax break that eliminates sales tax on data equipment. “We have been quite critical of the data center exemption,” said Schiller. “[The data companies] are benefitting pretty substantially, and these are not exactly giant job creating devices.”

In 2014, going under the name Vadata Inc., Amazon received $81 million in state incentives to build three data centers in Central Ohio with a total investment of $1.1 billion, in exchange for a total of 120 jobs with a payroll of $9.25 million a year, according to records from the state’s Development Services Agency. The bulk of the subsidy came from the data center tax break, and the remainder from a job creation program. New Albany provided its own 15-year tax property exemption to Amazon for a $300 million investment, in exchange for 25 jobs and $2 million in payroll, or an average of $80,000 a year.

In 2017, New Albany again agreed to a 15-year tax property exemption for Facebook, masquerades under the name Sidecat LLC, in exchange for a $750 million investment and 50 jobs with $4 million in payroll a year. The state offered $37 million in tax incentives, an even sweeter deal than Amazon’s.

In 2018, Google came knocking. Under the name Montauk Innovations, Google promised a $600 million data center, with 30 jobs paying $2.5 million in payroll a year, or roughly $83,000 per job. In addition to local tax breaks, Google received $43.5 million in tax credits from the state, which works out to an astounding $1.4 million per job.

Both Amazon and Facebook have since expanded their sites, which means additional tax breaks, additional jobs, and additional investment. However, since those are recent deals, some of the specifics are not available.

Honing in on the Amazon deal, we can do some quick math using the state numbers, since the state is required to value its tax breaks but municipalities are not. The state tax breaks alone translate to $675,000 in forfeited taxes per job, and a single person making $80,000 would have paid roughly $21,000 in taxes in 2018, so it would take roughly 32 years for the state to just break even.

New Albany was not Amazon’s only Ohio choice, notes Daphne Kenyon, an economist at Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. A number of Central Ohio towns were vying for the Amazon contract, and New Albany beat out the nearby Orange Township, where Amazon had initially planned to locate its data center.

On the local side, all three tech deals cleverly made use of Ohio’s Community Reinvestment Areas, a program designed to encourage investment in distressed areas. “If you look at the statute, it was originally supposed to be for places that housing was dilapidated. In New Albany is any housing dilapidated?” Kenyon said. “It looks to me like an instance of having a statute, where the tax breaks were supposed to be targeted at something that pulled at your heartstrings, but they drove a truck through it.”

The Amazon deal has more layers. The Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (PUCO) approved an agreement between Amazon and AEP that would provide Amazon with utility discounts over a 10-year term, that would increase as the company expanded in AEP territory.

The value of the discount was not disclosed and while PUCO stated that the cost wouldn’t be passed on to residents, the Office of the Ohio Consumers’ Counsel argued that was not the case, and AEP would likely find ways to make up the lost revenue, according to a Columbus First Business article.

“We understand that businesses need to be nimble and move quickly, and we have a history of working with companies to make the process of constructing a new site as smooth as possible,” McAfee said in response to a general question about the agreements with Google, Amazon and Facebook.

This close collaboration between the city and company of New Albany is true for all kinds of businesses who have chosen to locate there and is part of the New Albany Company’s master plan.

That “audacious idea,” according to the company’s website, was to “build an entire community where the enduring traditions of 19th century towns create harmony between the buildings and the land and a distinctive sense of place for those who live and work there.”

Wexner’s penchant for urban planning is not limited to New Albany.

He is credited with creating one of the first indoor-outdoor malls, the Easton Town Center, a precursor to today’s live-work-play model. And he has helped shape the city of Columbus and the Ohio State University through his influence and philanthropy.

And he’s not shy about it. In the early 2000s, a scuffle broke out over whether Wexner should have been reappointed to Ohio State University’s board, Wexner called a reporter and highlighted his philanthropic generosity. “If that makes you a fat cat, then that makes me the fattest cat,” Wexner said.

His more enduring legacy is on the way Columbus is governed. He is the founding member of the Columbus Partnership, a group of CEOs that influences economic development in the Ohio city known for its public-private partnerships.

In fact, the Partnership’s collaboration between the rich and powerful, and the city’s government, has been dubbed “The Columbus Way” by the Harvard Business Review.

Perhaps a more accurate description would be “The Wexner Way.”