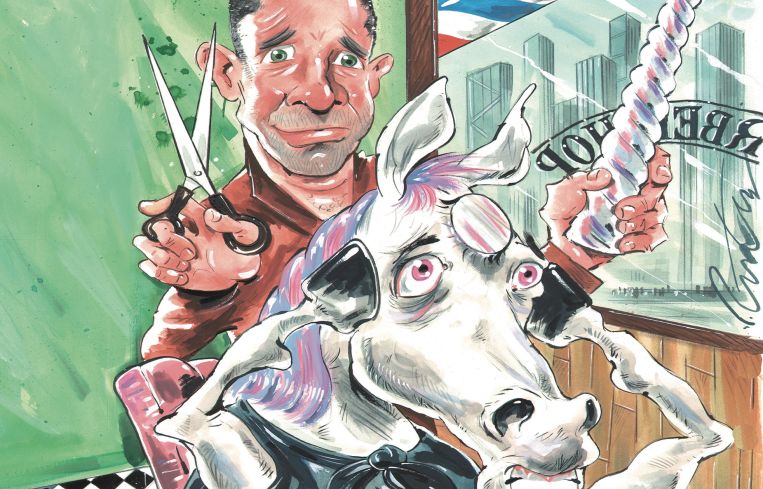

Is WeWork an Outlier, or Is Proptech Broken?

By Chava Gourarie October 29, 2019 10:00 am

reprints

The WeWork-shaped elephant in the proptech market just shrunk down to (maybe?) the size of a large cat.

After cancelling its IPO, firing its CEO, nearly running out of cash, and being rescued by its chief enabler — in under two months — WeWork’s valuation dropped to $8 billion last week, a long way down from the $47 billion tag it was awarded earlier this year.

The company’s near-implosion is reverberating through the venture capital ecosystem, where it’s forcing a reckoning for all the stakeholders involved: investment banks, venture capitalists, startup founders, institutional real estate companies, and very rich Japanese businessmen.

But where some see WeWork as a worrying sign of structural bloat that will result in a correction in startup valuations, others consider it an outlier that was primarily inflated by SoftBank Group, the Japanese conglomerate that gave WeWork its $47 billion valuation.

“SoftBank propped these companies up,” said Ben Levine, an executive at his family’s real estate development firm, Douglaston Development. “They were able to keep pouring gasoline onto the fires to keep them burning.”

WeWork’s valuation has exposed a fundamental disconnect between private valuation and public pricing. Venture funds are getting larger, and with billions of dollars to deploy; they’re churning out $100 million funding rounds and enthroning $1 billion unicorns at an increasing rate.

But the public markets are not having it. WeWork is only the most spectacular of IPO debacles this year from unprofitable venture-backed companies. Unicorn ridesharing rivals Lyft and Uber have both struggled in the public markets, SmileDirectClub and Peloton both had disastrous first trading days, and Postmates postponed its IPO until next year.

Analysts have pointed out that the brands that have suffered in the public markets are mostly consumer brands with a tech component, and quite far from the pure software companies on which the venture model is predicated. While WeWork is not a consumer brand in the sense that Peloton or Uber are, it shares a similar problem: Its economics are not remotely like a pure tech company.

Going forward, it is unlikely that investors will ignore the difference between a pure tech company and more capital-intensive business models. The question is how this shift will affect the way proptech companies in general, and workplace and short-term rental startups in particular, are valued.

Jamie Hodari, CEO and co-founder of WeWork rival Industrious, says that it’s a good thing for proptech. While VCs are freaking out, more traditional investors are relieved.

“Uniformly, people are basically saying, ‘Thank god,’ ” Hodari said. “They’ve all been petrified to put money into an industry where you have this SoftBank-funded Goliath that can behave in irrational or noneconomic ways.”

Venture math

In the real world, the math is simple: A company is considered successful if it produces more revenue than it costs to run it. Anything less than zero is failure.

In the startup world, math is more like alchemy. The key metric used for valuing a company is the revenue multiple, and since the revenue is the constant, the alchemy is figuring out what the multiple should be. While there are some rules of thumb that apply by sector, the multiple can be based on factors like growth rate, market features, and apparently, a founder’s charm quotient.

“For a pure SaaS [software as a service] company, the old rule is if the company is growing 300 percent, they should get 10x, then it’s got to double every year to maintain 10x,” said John Helm of RET Ventures, a venture firm whose capital is entirely sourced from institutional multifamily landlords.

That’s because the purpose of venture capital is to provide a runway for fledgling companies, so that they survive the growth stage and become profitable. For venture capitalists, the crucial metric is growth, since it points to a future win. As long as losses are accompanied by growth, it’s a sign that the startup is investing in its future; whereas a startup that becomes profitable too soon likely has no room to grow.

Of course, these metrics were devised initially for pure software companies, most of which work on a subscription model and by definition don’t require capital-intensive investments.

When it comes to a sector like proptech, the situation is very different. Not only are many proptech companies capital intensive, but even for software companies in the proptech world, the barriers to entry in real estate are high, because the industry is fragmented, the incumbents are entrenched, and down cycles are long.

That’s true for all proptech companies, which run the gamut from pure software to pure property plays, and include everything from data and AI platforms, to flex office and short-term rental startups, and marketplace companies like Opendoor or Airbnb.

WeWork, for example, had roughly $47 billion in lease obligations when they filed their S-1 in September, and about $3.4 billion in lease commitments. Of course, that’s because their model is to take on the term risk from landlords and then rent at higher price points. But at such numbers, it’s hard to justify not taking liabilities into account in the valuation.

That’s why it’s not an academic question as to whether WeWork is a real estate or a technology company, but it’s also not entirely fair to compare it directly to IWG, the shared workspace company formerly known as Regus.

Mature companies and growth companies should be valued differently, but clearly, the model applied to WeWork is no longer going to cut it for similar companies.

“Proptech companies that have good business models should be valued at multiples of revenue or gross profit, but that might be four or five times [the] profit, not 11 times,” said Hodari.

Tech or not?

Because real estate is by definition an illiquid and rigid sector — both capital intensive and deeply entrenched — proptech is something of its own animal within venture capital. Not only was it late to the venture game, but the sector only took off because institutional real estate companies finally decided to play ball, with institutional owners and developers both investing in proptech companies and beginning to implement technology into their portfolios.

“Companies are not trying to just sell software to real estate companies, they’re taking a full-stack approach and directly competing with incumbents,” said Zak Schwarzman of early-stage venture firm MetaProp. “Companies like those need a lot of capital.”

Clutter, for example, is a SoftBank-backed self-storage startup that is competing directly with institutional self-storage companies. It offers the same basic storage service as they do, with the added bonus that it will pack and move the client’s items for them, catalog their inventory online, and retrieve any item at the client’s convenience. Clutter raised $200 million earlier this year and used part of the funds to invest in real estate, purchasing the New York-based storage firm Storage Fox, and with it, four warehouses.

And these days, it’s often the incumbents fronting the capital, at least partially. Unlike many industries, the capital flowing into proptech is much more heavily influenced by industry players. Proptech has seen a tremendous influx of capital in the last few years from specialty firms like RET Ventures, Fifth Wall Ventures and Camber Creek, all of whom partner directly with institutional brokerages, developers and landlords.

For example, when Los Angeles-based Fifth Wall raised a $503 million fund earmarked for proptech investments in July, the investors in the fund included brokerages CBRE and Cushman & Wakefield, real estate investment firms Equity Residential and Related Companies, and hospitality firms Marriott International and Starwood Capital.

Helm, formerly the CFO of brokerage Marcus & Millichap, said that’s why he started RET Ventures, which is funded entirely by real estate companies. That way RET’s portfolio companies have access to its roster of investors — which include some of the biggest landlords in the country — allowing them to demo products, conduct market research, and scale quickly should they prove to have a quality offering.

Helm says RET’s model differs from generalist VCs, because it has assembled enough of the biggest players in its subsector — “rent tech” as Helm calls it — that it can influence a company’s outcome. That means the risk isn’t as high, so the returns don’t have to be either.

Fifth Wall’s founders have similarly touted their network of “corporates,” across a much broader array of tech sectors, and startups will often highlight when they’re backed by industry insiders.

Flexing

Because of this environment, where it takes both a lot of cash and often industry connections to succeed, there can be a winner-takes-all effect. For example, vacation rental company Sonder, which started with $450,000 in angel funding in 2014, raised $225 million in Series D funding in July at a $1 billion valuation.

“If they get the right capital partners around the table, the right initial customers, they can quickly look like a breakout,” said MetaProp’s Schwarzman, referring to Sonder.

In general, the flex businesses, workplace and short-term rentals have been a hot sector, and the amount of money that has flowed to the long list of companies in both is significant: Knotel received $400 million in September, raising it to unicorn status. Other companies like Industrious, Convene, and Breather in the workplace sector, and Zeus Living, Blueground, and Lyric in the short-term and extended-stay space have all raised above $50 million this year.

If you add global companies, like the Chinese Danke Apartments which raised $500 million this year, and the Indian Oyo Rooms, which is currently seeking to raise $1.5 billion at a $10 billion valuation, the amount of money directed at the flex and hospitality sectors is staggering.

Despite differing models across these companies, they are all closer to the real estate side of the spectrum than technology — something that real estate players have known all along.

“Everybody in the industry that understood the business model of WeWork didn’t understand its valuation at such a significant multiple,” said Douglaston’s Levine. That being said, he firmly believes in the business model itself, he said.

“The real estate-oriented VCs are much more sensitive and aware of this than the non-real estate VCs,” said RET’s Helm. “There’s been an influx of capital in some sectors at valuations that honestly leave us scratching our heads.”

He said the short-term leasing companies in particular need to be reevaluated, since they’re either management or real estate companies. “You got to use traditional valuation metrics for that,” he said. “They’re just master leasing.”

Hodari, of Industrious, whose company has partnered with companies like Macerich and Hines to manage shared workspaces in their buildings, also said that master leasing on its own is a tricky proposition, particularly in a downturn.

“If flexibility is the core of your value prop, you’re in trouble,” he said. “The reality is, you end up in a business that’s basically lease arbitrage.” His company has moved away from leasing and into management partnerships with landlords, with about 40 percent of its current locations in landlord partnerships. For new locations added in 2019, that number’s over 85 percent. “Everyone in the workplace world is trying to move to 100 percent managed, whether they admit it or not,” he said.

Industrious, which was founded in 2012, was only able to begin moving into partnerships after leasing and operating 55 locations and showing strong enough returns that they could sell landlords on the model. Since the landlord is putting up the capital and taking the risk, you have to be able to show landlords they can make 25 percent above market rent for them to be willing to shift to variable income, Hodari said.

That being said, many companies continue to highlight their tech credentials despite what’s fairly obvious to industry insiders. In conversations with the CEOs of Blueground, Zeus Living, and Sonder — as well as others — all have emphasized that their business is enabled by a proprietary tech platform, as well as a consumer-facing app.

And indeed, there’s no reason to downplay the tech component: The ability to manage pricing and occupancy for a constantly shifting global portfolio efficiently, as well as engage seamlessly with customers who value convenience and flexibility, is crucial to all these businesses, and sets them apart from incumbents.

“A tech-enabled real estate company is still a real estate company,” said Levine. “Whenever people saw technology or platform, they saw dollar signs, where people in the brick-and-mortar real estate industry didn’t understand how they could be valued for that.”

Still, MetaProp’s Schwarzman said he doesn’t expect to see a drastic correction, merely that people will get smarter about how they’re investing.

“Corrections tends to flow backwards from the public market. If it gets repriced in the public markets it trickles down to late stage, early stage, et cetera,” he said. “But in WeWork there’s a lot more nuance” because of how drastically it was overvalued based on its insistence that it was a tech company, he said. “Coming out of the WeWork experience, there will be a lot more scrutiny in that aspect of that business.”

Update: This story has been updated to reflect that 40 percent of Industrious locations are landlord partnerships, not 70 percent, as originally stated.