Will WeWork’s $47 Billion Valuation Hold After It Goes Public?

By Rebecca Baird-Remba August 13, 2019 11:31 am

reprints

WeWork, the start-up that defined the modern coworking trend, has a $47 billion valuation that could be pegged to smoke and mirrors.

Since its founding in 2010, WeWork (WE)’s roster of investors has been a veritable who’s who of the business world, including Amazon, Goldman Sachs, former Boston Properties chairman Mort Zuckerman, Fidelity Investments, J.P. Morgan Chase and Chinese private equity firm Hony Capital.

But SoftBank (SFTBY)’s $100 billion Vision Fund has become the biggest backer of WeWork, investing $10.4 billion in it so far. (The sovereign wealth funds of Saudi Arabia and the UAE are the two biggest backers of Vision Fund, with Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund having contributed $45 billion, far and away the largest investment.) The Japanese company headed by Masayoshi Son actually slashed its most recent investment in January from a planned $16 billion to $2 billion, citing a fluctuation in the global markets.

With each funding round, WeWork’s valuation has ballooned. It started at $97 million with its Series A in 2009, and by its Series C in 2011, investors had valued the coworking behemoth at $4.8 billion, according to Craft, a website that tracks corporate financial data. By 2015, WeWork’s valuation had reached $16 billion. Four billion dollars from Softbank last year boosted WeWork into $40 billion territory, and the funding round in January brought it to $47 billion.

J.P. Morgan Chase recently committed $800 million to a $6 billion debt package that depends on WeWork’s upcoming initial public offering raising at least $3 billion, Bloomberg reported last week. The bank is also expected to take the lead position in WeWork’s IPO, which is set to happen next month.

The We Company, as it’s now known, only shares its earnings calls and financial information with investors and declined to comment for this story. The coworking giant has, on occasion, sent its earnings to certain media outlets, but it declined to provide them to Commercial Observer.

There’s no question Softbank’s Saudi cash has fueled a rapid expansion in WeWork’s business. The company’s memberships have more than doubled year-over-year, from 220,000 in first quarter of 2018 to 466,000 in the first quarter of 2019, according to its most recent earnings update. It also more than doubled its revenue to $1.8 billion in 2018 compared to the year before. But that growth was accompanied by $1.9 billion in losses last year.

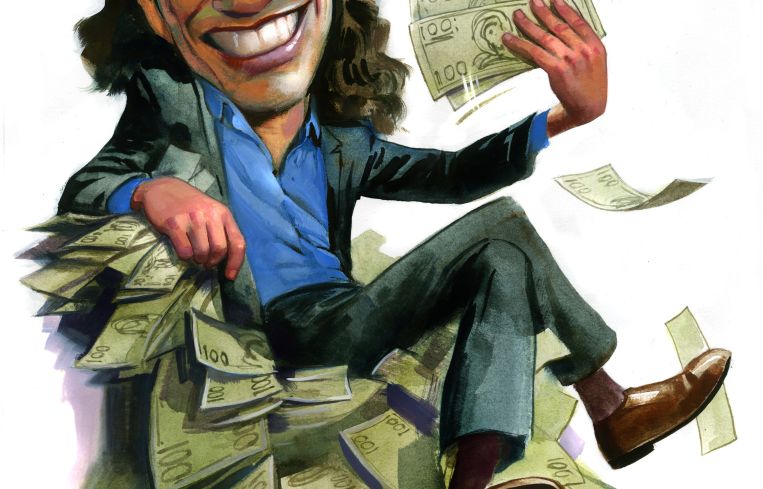

WeWork CEO Adam Neumann has made some questionable moves ahead of the potential IPO. He recently sold some of his stock in the company and borrowed against his holdings to generate roughly $700 million, according to the Wall Street Journal. The decision was surprising given that founders usually wait until after a company goes public to cash out their shares.

Neumann was also widely criticized after the Journal reported in January that he had been leasing to WeWork in buildings that he owned. He recently put one of those buildings, 88 University Place, on the market for $110 million, according to The Real Deal.

So what does all of this mean for the company’s IPO? It depends on who you ask.

Alexander Snyder, a senior analyst at CenterSquare Investment Management, called the valuation “a bit pie in the skyish; $47 billion assumes that WeWork is not only going to be the next Marriott, but [it] already is.”

He also noted that WeWork’s constant need to seek outside funding and inability to generate positive cash-flow signal a difficult future on the stock market.

“They’re not self-funded and the public markets aren’t particularly forgiving of companies that aren’t self-funding,” Snyder explained. The public markets are going to scrutinize their ability to grow without constantly coming back to the well. And if they can’t grow without constantly trying to raise money on the public markets, I’m not sure it’s going to be a very successful IPO.”

Market-watchers are waiting to see if WeWork’s debut on the public markets follows the same route as its highly valued, money-losing start-up peers Uber and Lyft. Uber just reported a $5.2 billion loss during its second quarter, roughly $3.9 billion of which was stock-based compensation that Uber paid to its employees after the IPO. The ride sharing company also just posted its slowest quarterly growth rate ever, according to The New York Times, with revenue growing to $3.1 billion, up 14 percent from last year. Lyft reported a $644 million loss in its second-quarter earnings, along with $867 million in revenue, a 72 percent increase year-over-year.

Snyder added that the success of the IPO will hinge on how WeWork sets its stock price. “One of the things you don’t want to do is set your stock price so high that it only has one way to go,” said Snyder. “I think they’ll price it reasonably, so it’ll just trade sideways.” He predicted that the IPO price “won’t be anywhere near $47 billion in implied valuation.”

Even fellow coworking CEOs (and, to be sure, WeWork’s biggest competitors) were split on how the IPO might go down.

Amol Sarva, the CEO of flexible office provider Knotel, argued that WeWork’s losses were large and it hadn’t “demonstrated its ability to weather a downturn.”

“WeWork is using lots of cash … to go public,” Sarva said in an email. “It isn’t what an IPO advisor would recommend — they aren’t ready.”

Ryan Simonetti, the CEO of Convene, felt that the IPO would be a big milestone even if it fails. “Regardless of whether it trades up or down, I think it’s a great thing for the industry and a great thing for our entire sector. It’s validation for the entire thesis [of coworking].”

Simonetti pointed out that his business model is somewhat different from WeWork’s. Over 80 percent of Convene’s revenue comes from non-coworking amenities that Convene operates in office buildings, including conference centers, event spaces, tenant lounges, catering and cafes.

“We don’t really view ourselves as a coworking company, we view ourselves as a hospitality provider for a Class A office building,” said Simonetti. “Regardless of how the IPO trades, I’m confident in our strategy and our ability to make money.”