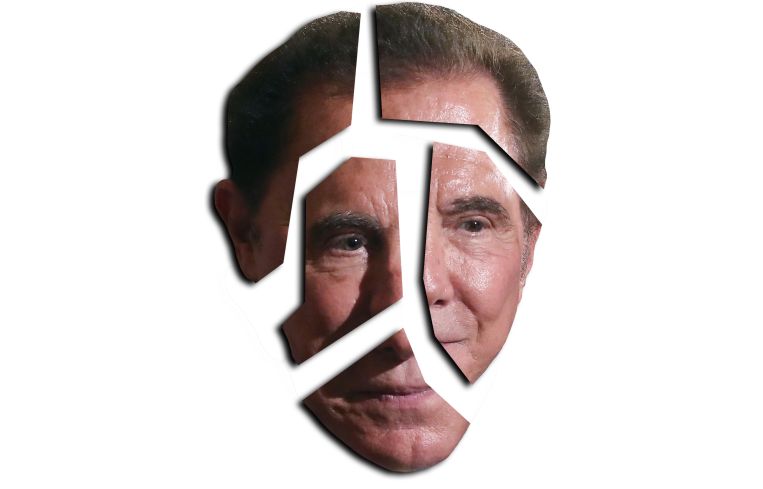

Will Steve Wynn’s Bad Behavior Haunt His Casinos?

By Sara Pepitone February 6, 2018 3:56 pm

reprints

Some felt the January blues worse than others this year. At the end of last month, in the week he turned 76, Steve Wynn, the chairman of Wynn Resorts, was accused of a history of sexual misconduct involving casino employees, became the subject of multiple investigations, saw his company’s shares fall by 10 percent and his company’s ratings downgraded by analysts and resigned as finance chairman for the Republican National Committee.

This could not have been good for Wynn’s casino and hospitality business, which had been going through what would have otherwise been a considerable surge of activity.

Last week, Wynn closed on the $336 million purchase of 38 acres of land directly across from Wynn Las Vegas on the Strip, a deal that creates a combined 280 acres of contiguous real estate. A spokesperson for the company declined to comment further, but a press release at the time of the announcement states the average cost of the full assembly of 280 acres is less than $3 million per acre and notes, “The future development of the land will further change tourist visitation patterns in Las Vegas.”

That’s a sentiment surely shared by a city (and state—44 percent of the total southern Nevada workforce has jobs in tourism) where visitor volume declined by 1.7 percent in 2017 and convention attendance rose by 5.3 percent in the same period.

Wynn is also in the midst of building a $2.4 billion casino in Massachusetts—but last month’s extensive exposé by The Wall Street Journal, which accused Wynn of pressuring employees to have sex with him (allegations he denies), has already snapped regulators into action. The Nevada Gaming Board, which grants licenses to casinos in Las Vegas, has announced an investigation of Wynn’s behavior, and the Massachusetts gambling commissioners also launched an investigation.

What will this mean for Wynn’s multibillion-dollar hotel and casino empire?

“Steve Wynn has generated trillions for this city,” said Marcus Threats, a Las Vegas-based hotel broker who has worked in Marcus & Millichap’s national hospitality group for nearly a decade. “Boston might be different, but the Nevada Gaming Control Board isn’t going to do anything. You don’t bite the hand that feeds you.”

But others are a lot less sanguine.

Last week, Colby Swartz, a senior managing director at Suzuki Capital, attended a conference of lenders across different asset classes who were discussing lending criteria. Many said they lent that on the assumption borrowers can do what they promised: get a stabilized asset and a fully functioning business up and running. “It may be easier for someone like Steve Wynn, but a proven track record may not even be enough today to secure financing. Public perception is a very large thing now. Will people consider these allegations, whether true or false, a reason not to stay there? It’s in the back of companies’ minds as they make decisions.”

But others believe that questions of Wynn’s personal reputation will pale next to the opportunity an experienced operator like him presents. “Irrespective of the allegations, whether they are proven or not, Las Vegas is on fire,” said Threats, who also teaches hotel finance at the Harrah Hotel College at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

That fire is fueled primarily by four projects: Las Vegas Stadium, 2020 home-to-be of the Raiders; Resorts World Las Vegas; the new convention center; and Fontainebleau, the still-unfinished 24.5-acre condominium and casino on the strip.

“Projects like these are creating construction jobs that haven’t existed since 2007, 2008 when CityCenter [the 67-acre mixed-use development opened in 2009] was being built,” Threats said. “Interest rates are lower than 2006. Bankers are looking to fund projects now. And the new Wynn site is a win-win.”

Threats suspected whatever is built there—presumably a hotel-casino that will employ 3,500 to 4,000 people full time—will be rushed to completion in anticipation of Las Vegas hosting the 2022 Super Bowl.

Meanwhile, in Massachusetts, the state Gaming Commission said the omission of mention of a $7.5 million settlement paid to a woman by Wynn in 2005 in the gaming license application is “critical” to the commission’s review and decision whether or not to approve. A prepared statement from Karen Wells, the director of the Investigations and Enforcement Bureau, noted their role is not to conduct a criminal investigation into sexual assault but, among other things, to review how the current situation potentially impacts the financial stability of the company.

A spokesperson for the commission told Commercial Observer there is no date set for a licensing decision.

But losing the license would be very bad for Wynn—and it’s a real possibility. Wynn’s 2016 Annual Report noted, “If the MGC [Massachusetts Gaming Commission] determines that we have violated the Gaming Act or any of its regulations, it could limit, condition, suspend or revoke our registrations and gaming license.” It also goes on to state such action “would have a significant negative effect on our Massachusetts gaming operation.” (Similar rules apply in Nevada where, according to the same report, disciplinary action may be necessary if it’s determined a licensee “reflects or tends to reflect, discredit or disrepute upon the State of Nevada or gaming in Nevada.” Until then, however, it’s business as usual in Las Vegas.)

Wynn’s 33-acre Massachusetts property (on the waterfront along the Mystic River), solicited more than $1 billion in subcontracted building services and supplies—via Suffolk Construction Company, a general contractor—one of the highest bid packages ever issued in Massachusetts for a private, union-built, single-phase development. Construction is beyond the halfway point of the 27-story, 3-million-square-foot building.

If it was not a casino, then what could it be?

Concerts and special events can extend hotel stays, food and beverage can be a draw, but how many U2 tickets or champagne and truffles do you need to sell to compete with, say, $174.4 million in a quarter, which is the reported casino revenues from Wynn’s Las Vegas operations for the third quarter of 2017? (This was, it should be noted, up from $153.2 million for the same period in 2016.)

With respect to the Boston property potentially operating without a gaming license, David Blatt, the CEO of CapStack Partners, an investment bank and adviser, said it could have viable use as a straight hospitality endeavor—but the lack of a casino would be a considerable blow to revenue. “The scale seems out of whack without that component,” he said.

Conventions may be a solution, Blatt said, adding, “I’d argue that day visitors and the activities the property could offer do not correlate one to one with gamblers.”

Furthermore, if a company does not generate gambling level of revenue, its level of financing will be more limited than it might normally obtain, and advances would be far lower. That said, Blatt does not think a decline in customers is imminent. “The association people have with the brand is of a certain caliber of hospitality. I don’t know that the greater population associates the name, the person, with the brand.”

Swartz agreed that meeting revenue expectations is vital to current and future financing. “There’s a lot of money to be put to work out there, but it’s not the free-for-all lending of a few years ago,” he noted.

Analysts are asking the same questions as gaming boards and investors.

Moody’s Investors Service downgraded Wynn’s corporate family rating to Ba3, from Ba2, lowered its long-term debt ratings and assigned a SGL-1 Speculative Grade Liquidity Rating. According to a prepared statement from Keith Foley, a senior vice president covering the gaming sector, “Although Moody’s expects Wynn will improve its leverage now that the Wynn Palace has opened and will begin to contribute EBITDA [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization] to offset the debt used to fund its construction, it’s not expected the company will be able to return to a leverage profile consistent with its former Ba2 Corporate Family Rating.”

S&P Global Ratings also changed its rating outlook—signaling the potential direction of the rating—on Wynn Resorts Ltd. and its subsidiaries: After 14 months maintaining a “stable” (not likely to change) outlook, the outlook is now “negative” (may be lowered) on the belief that these allegations could impact the company and its cash flow, said Melissa A. Long, a director and lead gaming analyst at S&P.

“If customers visit less, spend less, hold conventions elsewhere because of the stigma of the allegations,” Long said, the brand could be harmed.

This revised outlook, according to Long, means there’s a one-in-three chance the BB-minus rating—the same held by competitor MGM Resorts International—will be lowered over the coming one to two years. In the decade she’s been covering this industry with S&P, Long said she cannot recall a similar set of circumstances impacting a company. The team is monitoring the situation, watching gaming board and other investigations, regulatory reviews and possible leadership transitions and the form that might take, such as a need to buy out Steve Wynn’s 12 percent ownership stake.

“If Wynn is forced to step away from the company, it’s hard to imagine the company continuing to execute in the same manner without his influence,” said Mike Mixer, a Las Vegas-based executive managing director for Colliers International.

Noting the two Las Vegas top-of-market properties and the new developments (the new lot and one underway on the Wynn Golf Course property), the upscale, highly performing, Macau property and the in-progress Boston resort, he added, “The sheer size and scope of the Wynn portfolio limits the interest of potential suitors. Companies like Blackstone or Las Vegas Sands could feasibly take on a major acquisition like this, but few others make up the list of potential suitors.”

Otherwise, said Mixer, it is conceivable that the portfolio could be broken up—a Macau buyer, a Boston buyer and a Las Vegas buyer—to increase the number of potential suitors.

In which case, in poker parlance, action is on you.