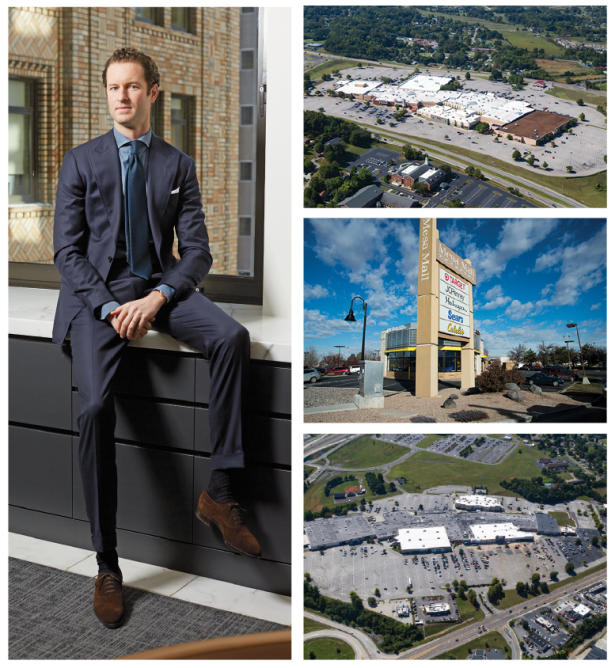

NKF’s Regional Mall Guru Thomas Dobrowski Is Taking Retail Doom and Gloom in Stride

By Lauren Elkies Schram January 10, 2018 9:30 am

reprints

Thomas Dobrowski might be one of the reasons why malls are not actually dying. And it’s not just because he sells regional malls, but because he arguably has been to more malls than anyone else (60 in 2017 alone), and whenever he visits one, he shops (that’s 60 purchases last year).

No, he’s not buying anything big—“just a couple small items I can throw in the bag,” the executive managing director at Newmark Knight Frank, said—but he’s still shopping at malls. And just that fact alone, he said, “inherently speaks to—when you get people in the mall they’re going to spend money.”

Dobrowski, who handles regional mall investment sales nationally, sold 13 regional malls last year. (Whenever he gets an assignment, not only does he tour the property he’s selling; he check out the mall’s competition.)

While there’s no doubting that malls, and retail in general, face headwinds—only five malls have either opened or are under development since 2007, while about 200 have closed in that time, Dobrowski said—the broker remains optimistic about the future of the industry. “The news does not help pricing. However, it does help bring attention and interest to mall properties for sale,” Dobrowski said, “because savvy investors recognize that this could be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pick up malls at good prices.”

Dobrowski didn’t start his career in the mall business. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree in finance from Villanova University he worked in Morgan Stanley’s real estate investment banking group. He got into the mall business at the now-defunct Rockwood Real Estate Advisors, where he worked from 2002 through 2014, before NKF came calling. The brokerage was looking to “grow a capital markets platform and grow a national brokerage business,” Dobrowski said.

Since then, Dobrowski has been NKF’s lone regional mall investment sales broker. With the help of a support staff of three who handle underwriting, analytics, materials preparation and research, he sold 13 out of the 30 brokered mall deals last year, making the sellers’ representative’s market share nearly 50 percent.

Being in a business that is not territory based, Dobrowski can be based anywhere in the country, but prefers New York City, his home for the last 18 years or so. (He, his wife and their 3-and-a-half year old son live in the East Village.)

As people continue to speculate about the future of malls, CO sat down with the 39-year-old broker at NKF’s digs at 125 Park Avenue last week to make sense of it all.

Commercial Observer: What’s your take on the doom-and-gloom mall headlines?

Dobrowski: My opinion is, it’s very overblown—the “death of the mall” headline.

Do you only deal with noncore assets?

Look, all the REITs want to hold onto their good assets obviously, or assets that they feel they can add value to so our business today is really split 50-50—50 percent of our sales come from the REITs that are shedding their non-core assets and then the other 50, plus or minus, come from [commercial mortgage-backed securities] special servicers and lenders that have taken back a lot of these malls over the last decade that were overleveraged and now are in many cases distressed. I grew this business out of the distressed mall market [back] in 2011, 2012 when malls started to sell again. A lot of the mall REITS, when these loans came due, and even today, when they come due, if they can’t refinance out of them, they’ll just give the keys back to the lender and that obviously is the beauty of CMBS financing. One of the best sources of lending for regional malls is CMBS debt.

Why is that?

I think because that’s where there is the biggest appetite for that type of loan. A lot of the insurance companies and a lot of the balance-sheet lenders typically have shied away from regional malls, just given the complexities behind them. They’re relatively illiquid in markets. And CMBS historically was the go-to source of financing [for regional malls]. That’s started to change now because obviously the headlines about malls are pretty tough. So that’s really why you see, [with] a lot of the sales today, the valuations are much lower than people ever really anticipated, even though we’re obviously in a really great economic cycle and there’s growth and retailers are doing well in many cases. But buyers are just underwriting out all of the risk associated with most malls. The proof is in the pudding. The reality is a lot of these malls are suffering around the country.

Have the mall owners found financing materially more difficult?

Yes. In the last 24 months, in particular, I would say financing has become one of the major hot points or constraints with respect to really selling bigger malls that require real financing. Because the equity check gets bigger, the number of players gets smaller who can stroke a big check to take down a $50-plus-million-dollar mall, which is a big deal today. Ten, 15 years ago, we were selling malls at $100 [million] and $200 million valuations. If you look at 2017, most malls were, call it between $20 million and $60 million, plus or minus, that sold.

How would you characterize lenders’ level of caution?

Well, much like buyers—but even more. They’re much more cautious where they are really concentrated on two or three main aspects. One is who the sponsor is: Do they have a track record? Do they have an expertise in the space? Because there are a lot of new owners and new buyers starting to enter the mall field today. Next, it’s starting to get into the property: Who are the anchors? What’s my anchor risk? Do I have a Sears, Bon-Ton, JCPenney, a Macy’s, kind of a lot of the anchors that are worrisome today for a lot of folks, and what does that risk look like in relation to really the rest of the mall and what are the options of re-tenanting those spaces? The third one is really then, Who’s the competition for that mall in that given market?

What are the most essential differentiating factors between malls with a positive outlook and those with more cause for concern?

I always give the comparison: It’s like a custom suit. From 50 feet away, your navy blue suit that you buy off the rack at Macy’s could look the same as the one you buy at Brioni, right? So when you look at a mall from an aerial, it could have Macy’s, Dillard’s and JCPenney and Sears and have very similar tenants on the inside, and that mall could be 10 miles outside Manhattan, and it’s killing it. But then you could take that same mall and put it in the middle of Ohio with the same tenant makeup: Once you get closer into it, [it’s floundering]. So what do we look at? I would say the big driver…is what are the options for that consumer in that market and what’s going to continue to drive them to continue to go to that mall into the future. If that mall is in a market that has two or three other malls but the market really only needs one…it’s going to be hard to make a case that [all three] need to exist. They may keep going for a while. Malls don’t die of heart attacks. They don’t die overnight. It takes a very long time for a mall to go away. It could take five years, it could take 10, it could take 15. Once you’re comfortable knowing that that mall can survive in that market, it’s then, What can I do to improve upon the tenant mix that is there today?

There’s enough there you don’t need to sell open-air shopping centers?

Correct. I can comfortably say we’re the only team probably in the country that can say we focuws 100 percent of our time and efforts on covering the regional mall market, which is why we have, arguably, the biggest market share, because we’re just ingrained in this sector.

What would you say is impacting malls besides e-commerce?

It’s changes in shoppers’ habits I would say and changes in the shopper demographic. I can give the example of, when I was growing up [in Holmdel, N.J.], it was always the mall where you bought everything, from soup to nuts. Right? Malls were woven into the social fabric. You hung out there. It was always where you sort of went shopping for back to school and holidays and everything in between. You first date at the movie theater was at the mall [and] you maybe ate at the food court.

What’s the biggest deal you’ve ever done?

The largest mall sale I ever worked on was a mall out in California called Stonestown Galleria, right outside San Francisco. We sold it for $312 million at the peak of the market [in August 2004]. It’s still a great asset. It’s still owned by [General Growth Properties].

What’s the last mall you sold?

Moreno Valley Mall in Moreno Valley, Calif. The all-in purchase price was $63 million. It was one of the bigger sales of 2017. It’s one of the best malls I’ve sold in the last five years.

Why?

It’s a complete contrarian story. This mall was foreclosed and taken over by CWCapital, a special servicer, in 2011. It’s one of the few malls, since they took ownership, it has only steadily improved year over year. And, it’s just a great case study in execution in terms of they brought in Round1 [entertainment company], they brought in Crunch Fitness, they brought in cool retailers that weren’t in that market before, and a lot of it has to do with Inland Empire California, which got hit really hard in the recession but has since emerged and exceeded expectations you can say in terms of population growth. And the mall stood to benefit from that. And we sold it to a private owner outside of Beverly Hills, [International Growth Properties]. This closed on Nov. 28, [2017].

How long does a mall typically take to sell?

Three to six months I would say is average. The time to sell them is not necessarily the part of selling malls that is most challenging.

What is?

It’s just the sheer complexity of the properties and the amount of time and effort that has to go into preparing offering materials and underwriting the asset that I think a lot of brokers would shy away from that, plus it’s a national product type and most brokers focus on regions, and that’s how most brokerage offices are set up. So we don’t sell anything in the immediate New York metro because there’s not really a mall market there.

Are you worried, with the death of mall stuff, about your future with this slice of the market?

I get that question a lot. A lot of people are like, Why do you put all of your chips in this basket, focus on this one product type? The answer is no. If you look at the peak of the market, there were 1,300 malls in the U.S., a well-established fact in 2007. Today, there are around 1,100. We’ve only lost 200 malls in 10 years’ time. If it took 10 years to get rid of 200 malls, is it another 10 or 20 of sales, trades, transactions to get these malls into the right hands of people that will really redevelop them, close them down and have them developed into something else? So, I think there’s a lot of runway left in terms of the number of sales that will happen over the next, call five to 10 years, and candidly, I think it’s only going to ramp up and increase. I think there’s going to be more transactions in 2018 than there were in 2017.