City of Goldman: The Mysterious Developer Who’s Transforming Brooklyn

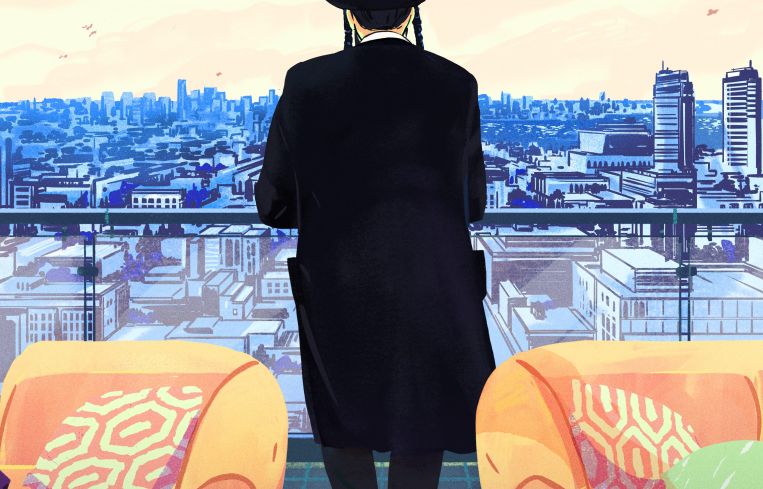

Yoel Goldman is the builder reinventing Williamsburg and Bushwick. Good luck finding a photo of him.

By Rey Mashayekhi September 13, 2017 10:00 am

reprints

Standing 23 stories and 250 feet tall, the William Vale Hotel towers over North Williamsburg, dwarfing virtually every other structure in proximity—a fact that affords the hotel panoramic, 360-degree views of New York City from its rooftop bar, Westlight, which attracts droves of young, sharply dressed New Yorkers who willingly stand in line to sip its $16 cocktails.

One person who, by all accounts, wouldn’t be caught dead drinking at the William Vale is the man who built it.

Yoel Goldman is a member of Brooklyn’s ultra-Orthodox Satmar Hasidic Jewish community—a sect that doesn’t usually go for rooftop outings. But that didn’t stop Goldman and his partner on the William Vale project, Zelig Weiss of Riverside Developers, from knowing that a 183-key luxury hotel on the corner of North 12th Street and Wythe Avenue with a sleek design and the right food and beverage offerings would be a roaring success.

“We can talk about what it is to go to a cool bar and have a cool restaurant, even though he doesn’t spend any time in cool bars at all,” said Eran Chen, the founder and executive director of architecture firm ODA New York and a frequent collaborator of Goldman’s (albeit not on the William Vale). “His feel and understanding of that context, and his thirst for knowledge and information, is huge. I was surprised, and consistently surprised, by his knowledge of what’s going on—what’s cool and what’s hip and what’s done in other places. And that’s been brought to the table in conversations.”

The opening of the William Vale last year represented a pinnacle for Goldman and his real estate firm, All Year Management. Having spent much of the 2000s gradually acquiring modestly sized multifamily properties across still-gestating Brooklyn neighborhoods like Crown Heights and Prospect Heights—often partnering with equity investors from the Satmar community—Goldman parlayed early success into a buying spree in the years following the financial crisis in 2008. His business plan, according to partners and collaborators, sought to capitalize on plummeted property values and Brooklyn’s promise as a burgeoning residential destination.

“He was one of our top two buyers in the early years of the recovery,” said Marcus & Millichap broker Shaun Riney, who specializes in the Brooklyn multifamily investment sales market. “Most of what he was buying was 20 units and less in these emerging neighborhoods. [All Year was] buying when no one else was buying. They were the ones cutting checks when you couldn’t get financing—when these neighborhoods looked nothing like they do today.”

Gradually, Goldman built a portfolio that now includes no less than 150 properties, the large majority of them residential and in Brooklyn. In the past several years, he’s pivoted toward more ambitious, ground-up projects like the William Vale and a massive residential development on the former Rheingold Brewery site in Bushwick that promises to bring more than 900 new rental units to the neighborhood. Having had the foresight to profit from Brooklyn’s relentless gentrification into a core market, Goldman is now facilitating that transformation as a builder.

In turn, Goldman, who has yet to reach 40 years of age and who one would be hard-pressed to find a photo of online (All Year Management did not return multiple requests for comment for this article), is only furthering his own status as one of New York City’s most active and influential real estate players—a devoutly religious man of modest means whose ambitious plans are reshaping the very face of Brooklyn.

“I think he’s transitioned from a very secure kind of business [as a multifamily landlord] to not only developing but developing new typologies,” said Chen, whose firm is designing the Rheingold Brewery project, as well as Goldman’s under-construction residential tower at 436 Albee Square in Downtown Brooklyn and a planned hotel on Bedford Avenue in Crown Heights.

“He’s attracted to bringing innovations to places that are underestimated and underdeveloped currently,” Chen said. “Anybody can buy land in Manhattan, but to buy 1 million square feet in Bushwick three years ago, when it still is to some degree not a mainstream place for high-end living, was a bold move.”

To help fund the William Vale and the Rheingold Brewery project, among his other developments, Goldman has issued roughly 1.7 billion shekels, or $485 million, in low-interest, publicly traded bonds on Israel’s Tel Aviv Stock Exchange. The bonds are backed by a portfolio of All Year’s New York real estate assets—the sorts of cash-generating, income-producing rental and hotel properties that Israeli institutional investors love to buy debt in.

Goldman, likewise, has shown an enthusiasm for the Israeli bond market as a vehicle to raise funds at cheap borrowing costs. With nearly $500 million in debt traded in Tel Aviv, All Year is one of the largest issuers among U.S.-based real estate companies to have completed bond offerings in Tel Aviv—a group that includes the likes of Related Companies, Lightstone Group and Extell Development Co., as well as more modest multifamily landlords like Spencer Equity Group, led by Goldman collaborator and fellow Hasidic community member Joel Gluck.

While not all of Goldman’s real estate assets are tied up in the holding portfolio backing the bonds, roughly three-quarters of them are—and those holdings have a combined equity value of around $480 million and a total asset value of nearly $1.5 billion, according to Israeli financial filings. Goldman does not own all of the assets in their entirety; to the contrary, he has partners on many of them, such as the William Vale. Still, for a man still in his 30s, he has managed to build an impressive business out of virtually nothing.

Unlike some in the Hasidic real estate investment community, Goldman did not rely on family connections or inherited funds for his entrée into real estate. Rather, he got his start at a very early age—sometime around his late-teens and early-20s, according to people who have worked with Goldman—through partnering with investors in the Satmar community to acquire and renovate small apartment buildings. (Like many in his community, however, Goldman was also married with children at a young age and by that point trying to earn a living for his family. Goldman’s youngest child was just born earlier this month, according to sources close to him.)

The work could be hands-on, with Goldman often laboring alongside subcontractors on the nitty-gritty of renovating properties. But he was able to stake his claim in the years leading up to the Great Recession, which prompted Goldman into action.

“These are guys who are opportunistic investors—they had a clear vision and saw opportunity and upside,” Derek Bestreich, the president of commercial brokerage Bestreich Realty Group and a former Marcus & Millichap broker, said of working with Goldman and his team at All Year Management. “They were able to take advantage of [the market] well in advance of that vision materializing. They saw the changes happening in Brooklyn and saw where things were going.”

The business model was simple: buy an undervalued building in a not-yet-gentrified neighborhood, fix up and renovate the property, charge higher rents for a better product and, as property values climb, refinance and reap the benefits (though seldom, if ever, sell).

“He was successful at executing his business plan,” Riney said, describing Goldman’s approach as done in the spirit of “If you build it, they will come.”

“They were buying 15 to 20 buildings a year, renovating these properties, refinancing them and doing it all over again,” he said. “As they were buying these properties, the rents were going through the roof. It was the right timing and the right location.”

Bestreich said that around the turn of the decade, Goldman and his associates were “the best buyers” a broker could ask for. “When they wanted something, they would pay the most, and they were the most hassle-free buyers imaginable,” he noted. “They would move really fast and get things done.”

He recalled one Prospect Heights building that “had all sorts of issues” including New York City Department of Buildings violations, cracked plumbing pipes and a crumbling façade. “I walked Yoel and his team through, and they looked at that stuff, but they didn’t acknowledge it,” Bestreich recalled. “He took me outside and said, ‘We’ll pay this price,’ and it was under contract two or three days later.” (All Year Management acquired the building, 690 Prospect Place, for a little over $1 million in 2011, according to city property records.)

“They knew where the market was going. We kicked up deal after deal after deal, and they gobbled it up time and time again,” Bestreich added. “They would pay the most—nobody else was going to pay what they were going to pay—and it turned out to be so true. Nobody knew it at the time, but they were so smart.”

Today, Goldman’s team at All Year and its sister contracting firm, Brooklyn GC, is said to number anywhere from 50 to 100 people—with Goldman’s empire far from a one-man operation.

Sources spoke at length about the caliber and competence of the people who work for Goldman, and they role they have played in building up his business. While many are members of the Satmar community, Goldman is also said to employ those of different religious persuasions in executive positions.

“He’s the head of the organization and the ultimate dealmaker and money guy, but he’s got a great team and network of really smart guys handling everything related to his business,” Bestreich said. “It’s not only him, and he would never say it’s only him.”

Talk to those who have known or worked with Goldman and one gets the impression of a charismatic figure for whom real estate is everything. Standing over six feet and decked out in traditional Hasidic garb, words like “presence” and “gravitas” come up when discussing Goldman, as does an appreciation for the man’s acumen and understanding for the way the business works.

“He looks at every single real estate project as a knot that needs to be untangled,” said Gary Katz from alternative lending firm Downtown Capital Partners, a frequent partner of Goldman’s. “He loves looking at a building and seeing how he can get more value out of it. He looks at everything as a problem he can solve.”

Riney described him as “an extremely humble, inquisitive, optimistic, visionary type of dude,” and said he believes intellectual challenges are what drive Goldman as a businessman. “I think people love to work with him. He has a smile on his face at all times and loves doing this—he lights up when he’s talking about [real estate]. It’s an outlet to exercise his mind.”

Goldman’s pivot into the realm of ground-up development was motivated by a couple of factors, sources said, including making the best and most efficient use of All Year’s resources and searching for greater value than could be found in a now-inflated Brooklyn investment sales market.

“If you’re doing a one-off transaction and trying to add 500 units to your portfolio, there are two ways to do it: one big project or you buy 50 10-unit buildings,” Riney said, recalling a conversation he had with Goldman on the matter. “His comment was, ‘I don’t have time to go to 50 closings and deal with 50 brokers and 50 attorneys.’ It’s too much of a headache; they literally have to focus on bigger projects.”

Bestreich noted that, in his estimation, All Year’s move into more ambitious development projects “is not a far-fetched transformation,” but “a logical next step” for a firm that has found its bread-and-butter market oversaturated in recent years.

“They were buying small buildings, renovating them, adding value and carrying out their vision—and then the market started to pick up, a lot of buyers started entering the market and doing the same thing,” Bestreich said. “Prices went up, and it became more expensive, and they weren’t able to do the same deals they were able to do previously. They had to find efficiencies, and that turned out to be in bigger deals.”

Over the past five years, All Year has partnered with Weiss’ Riverside Developers on the William Vale, Joel Gluck’s Spencer Equity on projects including the Albee Square development and, until an acrimonious and litigious split a couple of years ago, developer Toby Moskovits’ Heritage Equity Partners on a number of developments, including Moskovits’ Brooklyn Generator office project at 25 Kent Avenue in Williamsburg. (Moskovits declined to comment for this story.)

And in July, The Real Deal reported that Goldman was teaming with Kevin Maloney’s Property Markets Group—the developer of the supertall Steinway Tower on Billionaires’ Row—and the Hakim Organization to acquire a Gowanus development site for $50 million.

In addition to funds raised on the Israeli bond market, All Year also relies on financing from alternative lenders like Downtown Capital Partners and Madison Realty Capital—which earlier this year provided a $270 million construction loan on the Rheingold Brewery project—to fund its operations and activities. Sources said Goldman is happy to accommodate the higher borrowing costs associated with such lenders in exchange for greater flexibility to withdraw funds.

That flexibility enables All Year and Brooklyn GC to pay their subcontractors on time and often finish work ahead of schedule—a commitment to efficiency that, along with a zero-tolerance approach to construction safety violations that cause delays and tie up projects, collaborators consider a secret to Goldman’s success.

“He once told me, ‘Gary, on a spreadsheet, [finishing a project early by] three or six months looks like nothing,’ ” Downtown Capital Partners’ Katz recalled. “ ‘But if you finish a rental building in June of 2008 instead of September or October of 2008 [after the onset of the financial crisis], that’s the difference between a profit and a loss.’ ”

According to Israeli financial disclosures, Goldman’s assets have only appreciated in appraised value since he first tapped the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange in 2014, as has the cash flow coming into his portfolio as projects like the William Vale and his new rental development at 1040 Dean Street in Crown Heights have come online. The portfolio backing All Year’s Israeli bond issuance features roughly 1,500 operating rental units; factor in Goldman’s assets not included in the portfolio, and that number ranges anywhere from 2,000 to 2,500 total residential units, sources said.

Goldman’s success has not come without controversy, however. In 2015, Crain’s New York Business reported that All Year had attempted to raise rents on tenants at a number of Crown Heights buildings it had acquired in 2014—a move that would have violated city affordable housing regulations. While All Year eventually withdrew the rent increases—telling Crain’s that the hikes were “erroneous”—the episode was portrayed as an example of New York City landlords attempting to skirt rent regulations in search of profit.

In June, housing advocacy group Stabilizing NYC named All Year on its list of 10 “target landlords” that it said had exhibited “predatory” behavior—a list that included the likes of convicted slumlord Steve Croman and notorious property owner Ved Parkash. (Curiously, as of early September, All Year had been removed from Stabilizing NYC’s list. The advocacy group did not return requests for comment on All Year’s inclusion and subsequent removal from the list.)

And there has also been controversy over Goldman’s affordable housing plans for his Rheingold Brewery development at 123 Melrose Street in Bushwick. In June, DNAInfo reported that All Year and fellow Rheingold developer Rabsky Group had backtracked on nonbinding commitments made by the site’s previous owners regarding the number of designated affordable apartments at the development—a decision that would drop the project’s affordable unit count by as many as 88 units.

In addition to the question of affordable housing at the Rheingold project, there is also anxiety over the very nature of the development—one that promises to change the very makeup of the neighborhood via more than 900 new apartments and an innovative, outside-the-box design by Chen’s ODA.

Nearby 123 Melrose Street, Goldman’s friend and fellow Hasidic community member Simon Dushinsky, of Rabsky Group, is planning his own sizable residential development on the Rheingold site at 10 Montieth Street—one also designed by ODA and slated to bring around 500 rental units to market. Work on both projects is underway, and with Goldman and Dushinsky set to bring roughly 1,500 brand new units to the heart of Bushwick in a couple of years, questions have been raised about whether the market will absorb such an influx of supply in a timely manner—particularly at a time when rents have shown marked signs of softening.

“If you look at the very short term, it’s definitely going to be too much, too soon,” Bestreich said of the influx of units promised by the Rheingold developments. “But I do think it’s going to fill in. Real estate is not a quick, short-term game…I’m sure from the outside looking in, maybe it’s too much. But from the inside, I can almost guarantee it’s going to be a very good deal and work out just how [Goldman] expects and wants it to.”

Riney said that, in his estimation, Goldman’s Rheingold plans and his other designs on the city are about taking the next step as a developer and businessman—rather than just putting up more buildings for the sake of it.

“If you meet the guy, he wants the challenge” he said. “He’s someone who is not in need of money; he truly believes he’s now at a level where he can influence an entire area, like a Walentas and Dumbo. He’s looking for bigger swaths of land so he can create something special.”