Condition Red: How to Vet a Multimillion-Dollar Real Estate Deal

Thorough due diligence is the name of the game

By Rey Mashayekhi August 3, 2017 9:00 am

reprints

Steven Witkoff may be as savvy and experienced a real estate power player as any New York City has seen over the past 30-plus years—a man whose career has taken him from collecting rents in Washington Heights to owning some of Manhattan’s most iconic properties, leveraging himself to the point of nearly losing it all and then building his empire back up again.

But even Witkoff was unprepared for the curveball that was Jho Low, the playboy Malaysian businessman whose company, Jynwel Capital, financed the bulk of Witkoff’s $654 million acquisition of the 47-story Park Lane Hotel, at 36 Central Park South, in November 2013. With Low’s help, Witkoff would reposition the property as ultra-luxury residential condominiums—a seemingly can’t-miss proposition at the height of the Midtown luxury condo boom that begat Billionaires’ Row. Likewise, Wells Fargo—as credible and conservative a lender as any in the commercial real estate market—was onboard with the deal, providing an initial $267 million in acquisition financing to the developers.

Less than four years later, Witkoff’s designs on the Park Lane Hotel lay in tatters. Low is reportedly on the lam, with authorities in the U.S. and abroad accusing him of financing his global investments via a multibillion-dollar fund that doubled as a massive, fraudulent money laundering scheme. Today, under an agreement with the U.S. Department of Justice—which effectively seized Low’s stake in the Park Lane—Witkoff and his minority partners on the property are being forced to sell their stake in the hotel.

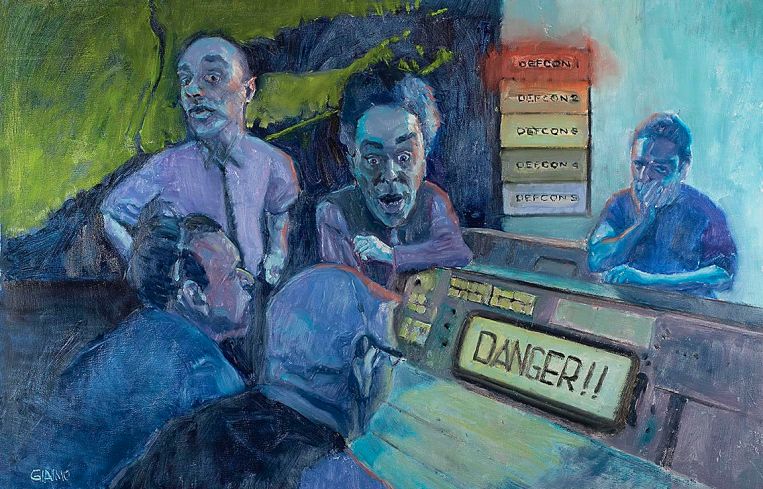

Whether Witkoff (who did not return requests for comment for this article) or Wells Fargo could have done more to better forecast what, exactly, they were getting themselves into with the Park Lane Hotel deal is unclear. But one thing is certain: In this age of shady investors and murky foreign capital sources, when tens (if not hundreds) of millions of dollars are at stake with virtually every deal, proper due diligence is more than just a formality for commercial real estate players. It can be the difference between a brilliant, career-making deal and a disastrous, potentially career-ending one.

Oftentimes, that due diligence isn’t anywhere near as dramatic as tales of dirty money derailing Manhattan luxury condo projects. Whether it’s a matter of the tenancy structure of an office building or the zoning regulations at a development site, real estate investors have plenty of homework to do before finalizing a transaction of any nature. If a deal checks all the boxes, investors can make a killing; if it doesn’t, or if the party involved fails to account for all the variables involved, things can fall apart rather quickly. Let’s face it: It’s why real estate attorneys are able to generate millions of dollars in legal fees annually.

“It’s not glorious, but it’s got to be done,” Mark Edelstein, the chair of law firm Morrison Foerster’s real estate group, said regarding the importance of proper legwork in evaluating a pending transaction. “Deals do sometimes crater based on facts that weren’t apparent at the time of the handshake.”

With that in mind, Commercial Observer spoke with a cadre of New York City real estate lawyers, consultants and developers to ascertain what they look out for before closing a deal to make sure no one gets hosed.

Know Thy Tenant

When buying a commercial property of any kind, it’s imperative to know exactly what your rent roll comprises and who it’s coming from. Leases can be complex, intricate financial agreements, and those tasked with vetting commercial properties often have their hands full verifying that such agreements are ironclad.

“Sometimes, with a commercial building, you’ll do due diligence on leases and find out that there are deferred tenant improvement obligations, sometimes there are options to renew at a lower-than-market rate, and sometimes there are termination rights that you don’t know about,” said real estate attorney Stephen Meister, a founding partner of law firm Meister Seelig & Fein.

Whether it’s attorneys like Meister or outside consultants like Jahn Brodwin of FTI Consulting, proper due diligence on commercial property transactions involves the buyer’s advisers combing through all of the leases at a given property and ensuring that their client knows exactly what they have on their hands—a level of detail not often provided by the investment sales brokers handling a deal.

“That means reading all the leases and thoroughly understanding all the things that could go wrong, all of the tenants’ rights under their leases and the creditworthiness of the tenants,” said Brodwin, a senior managing director in FTI’s real estate solutions practice. “Sometimes you’ll find early termination options, or tenants who may comprise a substantial amount of the rent roll and may be undergoing financial difficulties.”

Similar vetting applies to transactions involving multifamily properties, albeit pertaining more to the previous ownership and management of the asset. Compliance with rent regulations, for instance, are imperative to making sure the buyer isn’t subject to rent rebates or reductions in the future because of the former owner’s negligence.

For office and retail properties, Brodwin noted that the complexity of the due diligence depends not on the size or sale price of the property in question but the number of tenants on the rent roll. “If you’re buying a $1 billion building and you’ve got two tenants [at the property], that doesn’t take as long versus a property half the cost with 50 tenants,” he said.

He added that, in an ultra-competitive real estate market like New York City’s, buyers should start research early or face losing an asset to rival bidders.

“It’s not unusual for a billion-dollar property in Manhattan to give you a week’s due diligence or less,” Brodwin said. “In markets like New York, there’s a tremendous amount of liquidity and a lot of buyers. To be competitive, you try to do your due diligence in the bidding [process].”

Follow the Money

With so much liquidity splashing around the market, investors have to be more careful than ever about the equity partners they’re teaming up with. As unprecedented amounts of foreign capital fuel the current commercial real estate cycle, it’s up to the principals involved and their advisers to thoroughly vet any money being contributed to their venture, and the entities behind it.

That sort of due diligence will not only ensure that the pledged capital will be delivered by the parties who promised it but will also help developers like Witkoff avoid any unpleasant legal issues associated with equity of questionable legitimacy.

“The threshold issue is that it’s not dirty money and that the money is coming from where you know it’s coming from, not just where you think it’s coming from,” said Robert Ivanhoe, the chair of the global real estate practice at Greenberg Traurig. “We will usually fact-check as a law firm and make sure somebody isn’t on a watch list for terrorism or money laundering.”

Ivanhoe said that beyond issues of legality, there are “reputational issues and issues of certainty” to account for, as well.

“You shook hands with that investor, [but] did they understand what was expected from them as a partner?” he said. “I’ve definitely seen it happen where investors from abroad just haven’t performed. Sometimes they have an excuse, sometimes they don’t.”

In this regard, Ivanhoe said, “reference checks and bank and credit checks are important,” but he added that such measures are “not foolproof.” He noted that firms like Greenberg Traurig may go as far as retaining an outside investigative firm to more extensively dig up background information on certain parties—citing one transaction where the firm hired and worked “extensively” with a Swiss private investigator to probe the business dealings of a foreign investor.

“My client was concerned that the other guy’s money wasn’t real or wasn’t his,” Ivanhoe recalled. “We found that it was a sham and the potential partner was committing huge financial fraud, but it wasn’t in the U.S., so we couldn’t get U.S. authorities to do anything about it. I was the one, in essence, overseeing the investigation on behalf of the client.”

Jay Neveloff, who chairs law firm Kramer Levin’s real estate practice, said that such due diligence should apply on all sides of a transaction.

“If I’m a buyer of a property, I want to know who I’m dealing with because I want to know if they’re going to perform the obligations on their contract,” Neveloff said. “If I’m a seller, I want to know that my buyer has the means and the money to close and that the money is not coming from any questionable sources, because my deal can be held up. If I’m a lender, I want to know the reputation of the party I’m dealing with.”

And even if the party being vetted is perfectly legitimate, political conditions can often mean that capital commitments pledged from abroad could face obstacles in getting to the U.S. for investment—meaning one would ideally have assurance that the money is being sourced domestically, according to Brodwin.

“You want to make sure you know the sources where you money is coming from,” Brodwin said. “Certain countries are more complicated; if you’re dealing with those countries, you want to make sure the capital is domestic rather than oversees and that [the investor has] credit facilities here, cash available that’s already here, other business here.”

Edelstein, meanwhile, pointed to due diligence on funds raised through the heavily scrutinized EB-5 visa program as a relatively recent phenomenon. He noted that some developers hoping to rely on EB-5 funds initially overlook the fact that the program is subject to federal securities laws and that beneficiaries are accountable to their EB-5 investors.

“We tell [developers] all the same thing: You’ve got to do EB-5 right,” Edelstein said. “If you’ve done something wrong, you can be investigated by the [Securities and Exchange Commission] for a long time.”

In the Zone…and Other Considerations

For developers looking to build ground-up or redevelop an existing property, there are a myriad of concerns around zoning regulations that dictate what they can build.

“This is a very over-governed and overregulated city,” said attorney Joshua Stein, who runs his own eponymous real estate law practice. “If you’re doing a development project, you have to understand real estate taxes, zoning, building codes, incentives, the approval process and community opposition. The easy part is building your building; the hard part is getting approval.”

David Schwartz, a principal at development firm Slate Property Group, said it’s not uncommon for companies like his to retain a team of professionals with various backgrounds and areas of expertise—“Lawyers, architects, specialized zoning consultants, former city employees who have worked on the other side [of the approval process]: people who really understand the ins and outs”—to helm the due diligence process and consider a litany of potential roadblocks.

“You have to be ahead of the curve if [the Department of] City Planning is thinking of rezoning the area; what if they decide to downzone the area or landmark the area?” he said. “It’s very important to have a team of people who have done it a hundred times—people who have their finger on the pulse.”

Schwartz described zoning as the “most important” aspect of vetting a new development project given the diverse set of rules and regulations builders must play by. “It’s tricky,” he noted. “You want to make sure you really understand the zoning, because now pretty much every new zoning district has special rules to it. An R6 zone in Flushing [Queens] may be different from an R6 in Downtown Brooklyn.”

Other facets of the process to be accounted for include environmental regulations related to a given property—such as those that were previously contaminated due to industrial use—were subsequently designated as a federal Superfund site and have ongoing obligations under the Superfund program. Schwartz mentioned one property that came with “an environmental problem,” which had led another prospective buyer to walk away from the deal but which Slate bought after bringing in “a very strong environmental team” to help guide the development.

And sometimes, due diligence can be as simple as knowing what, exactly, you’re buying. Edelstein relayed one transaction where a client was about to buy a suburban shopping center only to find out that the seller didn’t even own the retail strip’s primary parking lot. “Most of the parking was at an adjacent parcel, and we weren’t buying it,” he recalled, adding that the situation would have meant his client was “effectively buying an illegal use” given zoning requirements mandating adequate parking space. The situation, he said, prompted a “complete reworking of the deal.”

“[Due diligence] really is essential because our clients are moving so quickly; they can sign a letter of intent that’s only a page long, and only when you start digging deep do you find out what they’re actually buying,” Edelstein said.

Kramer Levin’s Neveloff cited a number of other, seemingly smaller considerations—such as whether a property has a valid certificate of occupancy and all the necessary insurance coverage—as nevertheless vital to due diligence of a pending transaction.

“The whole point is to find out the facts and assess the risk,” he said. “I can think of any number of situations where we did the due diligence and the client ultimately walked away from the deal because they didn’t think they would have the money or the financing, or there were zoning or land use or [New York City] Department of Buildings issues.”

Yet not all developers are gun shy when the time comes to pull the trigger on a deal, no matter what their legal counsel may advise. “There will come a time where there is a risk, and the developer has to decide to take the risk or not,” Schwartz said. “It’s about taking a calculated risk versus no risk.”

He added that, oftentimes, the extent to which developers are willing to perform their due diligence—or follow up on what that due diligence has found—depends on the greater state of the market and the value of the opportunity. “The hotter the market, the less due diligence,” Schwartz said.

At that point, it’s up to the lawyers tasked with guiding their clients through the minefield that is the world of commercial real estate to speak their minds and tell them how things could go before anything is finalized.

“As a lawyer, you’re the voice of the future—we’re supposed to think about whether a deal makes sense, and if we have misgivings we’re supposed to share them,” Stein said. “It’s not a very popular position. But typically our principals are pretty smart; if they’re doing something we don’t think is a good idea, we speak up, and if we’re right about that hopefully we can persuade them why.”

And if they can’t?

“The deal comes in, everyone is excited about it, and they want to get it closed up as soon as possible,” he said. “And then you have 10 years or sometimes even 99 years in which to regret what’s in the document.”