Inheriting a Great Real Estate Empire Is More Complicated Than It Looks

By Lauren Elkies Schram August 17, 2016 9:00 am

reprints

Just being born into one of New York City’s family-owned real estate firms does not guarantee you a spot in the C-suite.

At least, not at Rudin Management.

“You have to show passion and commitment and a desire to be in the business,” said William Rudin, the third-generation chief executive officer of the firm, whose children have taken on larger and larger roles in recent years. “It goes from there. You have to work for it and earn everybody’s confidence, show a commitment and work hard.”

Anything other than that, Rudin added, “would be irresponsible.”

Responsibility is one of those watchwords for those who have a kingdom to look after—which they likewise pass on to the next generation.

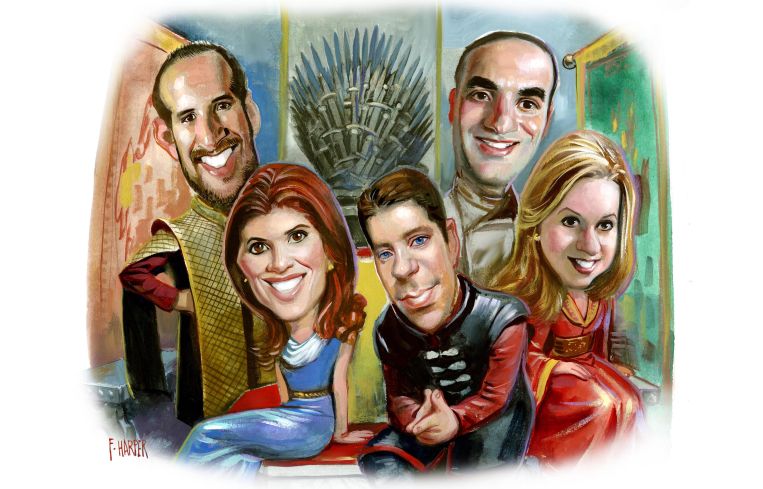

One of New York City real estate’s most fascinating aspects is the aristocratic underpinnings of its most powerful families. Real estate represents a kind of landed gentry in a country that never had nobility—and nobility (particularly issues of succession) has always been the stuff of literature.

The big names—Durst, Fisher, LeFrak—have their own family sagas, their own courts, their own vassals and serfs. And they always have a new generation of princelings at the helm.

Patricia Angus, an adjunct professor at Columbia Business School who teaches a class on family enterprise and wealth and has been instrumental in creating a family business program there, said family members need to be frank about the strengths and weaknesses of heirs before assigning them roles.

“A business always deserves to be run by the most capable and qualified people—whether family or not,” Angus said. “If a family member is not qualified, it should not be assumed that they will become a manager of the family business. That is not good for the business, or the family. If a family member has a problem with excessive spending, the family needs to think about the root causes. Is there a mental health issue? Substance abuse? Some other explanation for the spending? And, what can be done about it? Making sure that all family members live healthy, productive lives is a top priority for almost all families. During the estate planning process, it is important to have honest discussions of these issues.”

Winston Fisher, a third-generation principal at Fisher Brothers, said his father, Richard Fisher, told him he had to work outside of the company before joining the family firm.

“He was like, ‘Listen you cannot work here,’ ” Winston, 43, said. “‘You have to work outside of the company. You cannot come in here as a family member with no experience. When you walk through this door, your last name is not Fisher. When you walk through this door, you are a worker, and you are going to behave like a worker…If you can’t do it, you’re out.’ ”

Winston’s cousin, Kenneth Fisher, a company principal, added, “Also there was no revolving door. Don’t ever come in and spend a couple years here and say, ‘You know what, I’m gonna go try something else, but I’ll be back in two years.’ That’s not the way it worked either. If you left, you left.”

For many scions of these New York City real estate empires, seeds were planted when they were still in high school around the dinner table.

“My father and grandfather would be arguing at one side of the table, and my grandmother would be trying to avert our attention away from it,” said Eric Gural, a co-CEO of Newmark Holdings and son of the company’s chairman, Jeffrey Gural. “I wanted to know what they were arguing about and who was right.”

In the Gural family’s case, the arguments were usually about Jeffrey acquiring a lot of property, and Jeffrey’s father, Aaron, “generally warning him against the risks,” Eric said. “My dad and Barry [Gosin, his business partner,] were a bit more bullish than my grandfather who was more concerned about the cost of purchasing all these properties, but looking back my dad was right. However, it showed that my grandfather cared a great deal about what was happening to the business.”

Eric, 48, got his entrée to the business working at Newmark Holdings’ portfolio buildings as a porter and freight operator during summers off from high school. (The company portfolio spans about 10 million square feet.) This summer, Eric’s 18-year-old son, Ethan, is working at the company for a month, operating the elevators at Newmark Holdings’ 247 West 37th Street.

Eric’s cousin and co-CEO, Brian Steinwurtzel, started at Newmark Holdings as an intern over the summer at age 16, collecting rent at 318 West 39th Street and 247 West 37th Street.

“Anyone who has an interest, we want them to have an opportunity to see what we do,” Steinwurtzel said.

To that end, all family members have to do a stint as a leasing agent, an asset manager, a property manager and do a little bit of work on the legal end “so we get a good sense of what each other does,” Steinwurtzel, 39, said. Even Anny Pahl, the company’s general counsel and Jeffrey Gural’s niece, circulated through all of the jobs.

This is fairly typical, according to Elisa Balabram, who has been teaching family business management courses at Zicklin School of Business at Baruch College since 2013.

Company heads groom the next generations by “providing internship opportunities, summer jobs, teaching them financial responsibility, showing them how the business works and once they choose to join the business, allowing them to start with an entry-level position, and grow over time and by mentoring them into becoming the next leaders. It is crucial to encourage next generation family members to work elsewhere, to gain experience and build their credibility, and to allow them to choose or not to join the business later on.”

Justin Elghanayan, who is the president of Rockrose Development Corp., described the wooing into the family business after a stint as a teacher this way:

“I did talk to [my father] a lot about business,” Elghanayan, 38, said. “But he really didn’t pressure me. It was more like a long, slow seduction. And when I tried it, it was just really fun and really interesting. Then I spent several years at the beginning with the company working in different roles in the company, sort of from the bottom up [before] taking on a more executive role. It got to be even more fun because I got to do more creative things—like what we’re doing in [the] Court Square [neighborhood of Queens] requires some creative thinking where we’re developing 2,500 units of housing.”

William Rudin (now 61) would tag along with his father, uncle and grandfather at construction sites “as early as 4 years old” and would frequent the company headquarters at 415 Madison Avenue.

When he was coming-of-age, his grandfather, the late Samuel Rudin, made William an interesting offer.

“He wanted all of his grandchildren to come into the business,” William said. “He said to me, ‘Don’t go to college. Put a chair in my office, and you’ll learn more in a month than in a couple years in college.’ ”

William turned down the opportunity, and his grandfather passed away while he was in school.

“I sort of regret not taking advantage of that opportunity,” William said.

William’s children, who are executives at Rudin Management, started learning about and working at the company early on.

“In 2007, a year after graduating from college, I didn’t put my desk in my dad’s office, but I sat in the office of our chief operating officer, John Gilbert, and started there and was included and invited to every meeting and just started to learn how the business worked,” said Samantha Rudin Earls, 32, a company vice president.

Her brother, Michael Rudin, (now 31 and a vice president at the company) did the same thing in high school.

“I took a semester off from school and basically shadowed our father, and like Sammy did a few years later, my desk was in our chief operating officer’s office,” Michael said.

For the senior members of the family, it is understandable that they would want to pass the business on to their heirs—but the pressure to join the business is nowhere near as widespread as it once was.

Richard LeFrak, who is turning 71 on Aug. 29 and the third-generation chairman and CEO of LeFrak, told Commercial Observer he felt pressure to join the family business—but the same rules don’t apply to his kids.

The general consensus among all the families contacted by CO was that the younger generation can do as they wish—but they know they can always join the family business if they want to.

“You want your kids to follow in your footsteps—of course, you do,” said Kenneth Fisher, 58. His daughter Crystal Fisher, 35, has done some work for the company, and he has a 22-year-old daughter and a 20-year-old son, both of whom are in college. “But at the end of the day, I want happy kids. I don’t want kids that go to work every day and have trouble getting dressed because they don’t want to come in because they don’t like what they’re doing. So the most important thing is groom them if they want to be groomed.”

“I struggled with whether I liked real estate because I grew up in the business—or whether I liked it because I would have liked it regardless,” said Andrea Olshan, 36, the CEO of Olshan Properties, the New York City-based real estate empire of approximately 24 million square feet spread over 11 states, which was started by her father, Mort, who is now the company’s chairman. “Ultimately, I came to realize it’s probably both.”

Olshan added, “My mother actually always thought I would make a great attorney and probably still wishes I had gone to law school.”

In some families, there’s an impulse from the younger members to strike out on their own—within the real estate business or not—to establish their bona fides.

That’s what Jonathan Iger, the 34-year-old, newly minted CEO of William Kaufman Organization, did until 2010. He was working at a Washington, D.C., real estate boutique investment firm when his late grandfather, Robert Kaufman, who was 83 at the time, approached him.

“Robert was ramping up for a new cycle,” said Iger, the fourth-generation company head who was thrust into the role after Kaufman died early this year. “That’s partially why I came aboard.”

At The Durst Organization, family members interested in the business have to start as an unpaid intern for two years, working “in all of the various departments including a stint in the engine room, management office, in leasing, on the financial end, so they understand everything that goes on here,” said Douglas Durst, the chairman and a third-generation leader of the company.

Content with working at Diesel Construction, Jeffrey Gural had no interest in going into the family business.

“My father and his partners had been bugging me for a couple of years to leave Diesel and come to work there,” Gural said. “I was the only one of the children of the partners who could really do it.”

But when Diesel Construction was sold to ARA Services, Gural didn’t want to work for a public company, so he decided to try out the family business. (In a stroke of irony, Newmark Grubb Knight Frank, where Gural is chairman, was sold to BGC Partners—a public company.)

“I’m a civil engineer. My real love has always been construction,” Gural said. “[But] I don’t regret it at all obviously, especially now. These buildings are worth so much money.”

For many successful real estate families, it has been paramount to have clearly outlined job descriptions.

“It is important to determine the roles and responsibilities of the family members involved in the business, to establish rules to determine who can join the business, to have governance in place—family council, family meetings, board of directors with independent members, a family constitution, to name a few—and to be crystal clear on the family values, vision and goals,” Balabram, the Baruch professor, said in an email.

Lessons about division of labor can sometimes be learned the hard way.

“My father and I used to fight all of the time,” Jeffrey Gural noted. “Finally, we came up with an ideal plan. He would oversee certain buildings, and I would oversee certain buildings. And we never fought again.”

Steinwurtzel and Eric Gural “determine who has the best skill set for each project and the time [to do it],” Steinwertzel said.

For buildings that require a lot of leasing, Eric Gural handles the job. If they are heavy on financing, Steinwurtzel takes them.

At Durst, the job descriptions are inherent in the titles: Douglas Durst is the chairman; his cousin Jody Durst is the president; Douglas’ son Alexander Durst is the chief development officer; Douglas’ daughter Helena Durst is the chief administrative officer; his cousin Kristoffer Durst is the chief information officer; his niece’s husband David Neil is the chief leasing administrative and legal services officer; and Jody’s son Lucas Durst is a project associate in the leasing department.

‘The odds of a family business succeeding into a third generation is a rare happening…third-generation heirs are raised in a very different environment and [have] a lack of shared common goals or outlook for the future.’

—James Olan Hutcheson

Richard LeFrak runs the eponymous firm with his sons James LeFrak, 42, and Harrison LeFrak, 44, both vice chairmen and managing directors. Harrison handles the family’s Florida portfolio and is “very adept at finance, [so] he does a lot of the family investing,” Richard said; James focuses on construction, development issues and handles the California properties.

At the end of the day, Richard added, no one is forced to do anything.

“The responsibility is taken; it’s not given,” he said. “It’s a family business. If someone wants to work on something, they do.”

Justin Elghanayan is responsible for construction, development, residential acquisitions and neighborhood building at Rockrose; his dad handles finance and commercial acquisitions.

“I think it’s a really good way to organize any partnership, but particularly for an inter-generational partnership I think it works really well,” Elghanayan said.

As with other types of businesses, there are merits to working at the family company, as there are potential pitfalls.

“The pros of working in the family business include not having to start a career from scratch and benefitting from the success and reputation already in place,” said Sally Jennings, who teaches a course at New York University School of Professional Studies in real estate family business management. “If there is naturally a strong relationship between family members or at least shared respect, the bond can increase. The cons are frustration due to lack of ability or interest from successive generations; inability to work well with family members; and radically different management styles that turnoff other employees.”

For Jennings, teaching a course at NYU was personal. She is the second-generation president of Realty Capital International, a real estate investment banking and advisory firm.

“My idea to teach a course at New York University in real estate family business management stems from my own experience and desire to help successive generations avoid the pitfalls of joining a family business,” Jennings said. “There are special considerations for a family business including estate planning, accounting, legal and psychological factors that will all determine the success or failure of the business.”

Those issues are not always easy to sort out. That is why Angus from Columbia University established Angus Advisory Group. As a consultant, she works with families who have multigenerational businesses, trusts and wealth and helps them work together across generations to understand what they own, how they own and how to think strategically.

“Real estate families are really interesting,” Angus said. “In part they’re interesting because of the nature of real estate itself. It’s this very tangible asset that lasts longer than human beings and is often co-owned through family members through structures and often among multiple families.”

The main issues she has worked on with half a dozen real estate families are how do members work together, how to avoid conflicts, understand estate plans and legal structures and ensure they are still running a productive business. In addition, she helps sort out when someone from outside the family should be tapped to manage it.

“That may involve some family members being involved as overseer. Others may be shareholders; others may be bought out,” she said.

Having a family business that gets successfully passed down from generation to generation is actually uncommon.

Only about 44 percent of family firms make it into the second generation as a family business, 10 percent will succeed into a third generation and about 4 percent into a fourth generation, according to James Olan Hutcheson, the president and founder of family business consulting firm ReGENERATION Partners. “The odds of a family business succeeding into a third generation is a rare happening,” he said. “[There are] many reasons for this, but primary among the reasons are that third-generation heirs are raised in a very different environment and [have] a lack of shared common goals or outlook for the future.”

One real estate family that famously split was the Elghanayans. Brothers Henry, Thomas and Fredrick Elghanayan founded Rockrose Development in 1970 but parted ways in 2009 with Henry, the eldest, retaining Rockrose and the two others launching TF Cornerstone.

The Real Deal reported that the Elghanayan brothers split over differences about a succession plan. “There’s some tension, but if you think of all the divisions that have happened in the real estate industry, this was a rather smooth one,” Henry Elghanayan told the publication.

“The concept was in the long term, there were probably going to be so many people and so many personalities involved,” Justin Elghanayan, the junior partner and heir apparent at Rockrose recently, told CO. (Justin Elghanayan has two other brothers—Adam and Ben—neither of whom are in real estate.) “We saw what happened to family businesses, and it can create conflict. We didn’t want that to happen. I really like my cousins. We thought it was cleaner to do it this way.”

It can be challenging for senior members of a clan to retire and not micromanage the succeeding generations.

“A lot of these people are deal junkies,” said Barry Hersh, a clinical associate professor at the NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate. “The question is, When are they willing to let go?”

“My father, when he was alive, obviously he was in charge of certain things,” said Winston Fisher, “but he was able to let go of the reins and pass things on at the same time. They encouraged the second and third generations to have their own voice. Kenny, Steven and I manage the company differently and do different investments than the second generation. We’re different and so we have core philosophies that are passed down but we are looking at different things than they did. And that’s okay.”

The secret sauce of present-day Newmark Holdings, Jeffrey Gural said, is letting his son and nephew run the business.

“Fortunately for them, I really am focused on my racetracks and casinos and my nonprofit boards,” Gural said. “I don’t know what would happen if I didn’t have [them].”

With additional reporting provided by Terence Cullen.